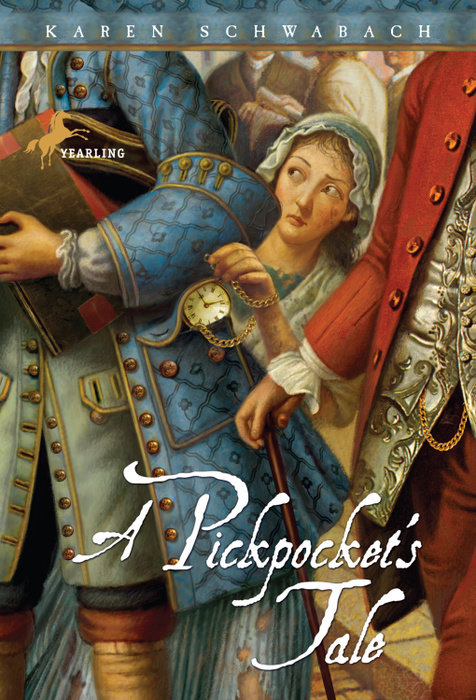

A Pickpocket's Tale

A perfect Common Core tie-in, A Pickpocket's Tale includes nonfiction backmatter with a historical map of New York City in 1730, a glossary of period vocabulary words, and an explanatory note titled "How Much of This Story Is True?"

Molly Abraham is a kinchin mort: a ten-year-old thief trying not to starve on the London streets. But everything changes for Molly when she is sentenced to be transported to the American colonies. She becomes an indentured servant to a kind Jewish family in New York City, and Molly has it good. So why is it that all she wants to do is go back to London?

Karen Schwabach uses richly detailed descriptions and authentic period language to bring history to life. She skillfully explores the subjects of Jewish culture in Colonial America and London street culture in this gritty yet heartwarming debut novel.

An Excerpt fromA Pickpocket's Tale

One

“The Law is!” The judge adjusted the black velvet cap atop his full-bottomed white wig and gazed down at the manacled prisoner before him in the cobbled court of Sessions House Yard. He looked around at the other chained prisoners waiting in the cold, open yard, then over at the dismal huddle of people whom he had already sentenced.

He pursed his lips and continued. “That you shall return from here, to the place whence you came. And from there to the Place of Execution. Where you shall hang by the neck until the body be dead! Dead! Dead! And the Lord have mercy on your soul.”

The prisoner gasped and turned white. He stumbled backward, stricken. The judge smiled in grim satisfaction while the bailiffs dragged the prisoner off to a corner to join the others who had been condemned.

Molly shifted from one aching foot to the other, trying to ease the weight of the chains on her ankles. It was the fourth death sentence she had heard that morning, Molly thought, or maybe the fifth. It wasn’t getting any easier to guess what the judge was going to say when her turn came. Everyone knew that you could be hanged for stealing anything worth more than a shilling, in London in this year 1730. Even if it was your first offense. Or you could steal more than that, a dozen times, and live. And it didn’t seem to matter if you were only ten years old, like Molly, or really old . . . forty, even. There was no way of telling how it worked.

You couldn’t tell bleedin’ much from the judge’s speeches either, Molly thought. He sat there like a great, gloating carrion crow, looking down at the prisoners from his high perch. He talked a lot of bleedin’ rubbish about their sins, and the great wisdom and mercy of the law, and the love of the King for his subjects, and he said that some sins (like stealing a knife or a ring) were too great to be forgiven on earth. And while he talked, he fingered the black velvet cap that he put on for death sentences and turned it slowly in his hands, looking from the cap to the prisoner and from the prisoner to the cap. There was no way you could tell whether he was going to say the cramping-words—the death sentence—or something else until he either clapped the black hat on his head or else set it gently down among the piles of flowers on the high bench before him.

Today was a sentencing day. The prisoners had already been found guilty. They had been waiting in the yard since before the first dim rays of December dawn melted the frost on the cobbles. Molly longed for something to eat. Something to eat, and something warm on her hands and feet. Some of the prisoners had stuffed straw into their shoes to keep out the cold, but Molly’s wood-and-leather clogs didn’t have any room for straw in them. They were too small as it was. Molly had grown in the months she’d been in prison. Her skinny wrists stuck out from her sleeves, and the hem of her linsey-woolsey dress and the shift underneath hung almost two inches above her ankles, showing the too-big gray woolen stockings that had been her mother’s. She caught sight of her reflection in a puddle at her feet. Dark brown eyes stared out of a thin, pale face. Her tangled black hair just reached her shoulders. It had been longer once, but she had cut it off two years ago when she’d had the smallpox.

Molly looked up at the other chained prisoners near her and tried to guess something about her fate from them. It seemed like the bailiffs and turnkeys were herding people together who were going to get the same sentences. Well, One-Eyed Jake was near her. He was a flash-cove on the Rattling Lay, stealing from coaches. Molly had seen him do it—sneaking among coaches that were stuck in the mass of vehicles crammed together, trying to get through the narrow city gates. He would quietly slice through the leather top of a carriage and take whatever he could find inside.

Then there was another kinchin mort like herself. Molly stiffened as she recognized Hesper Crudge. Molly had never spoken to Hesper, but she knew who Hesper was. Everyone did. At least everyone on the canting lay—all the thieves of London. Hesper had a reputation for blowing the gab. If you reported someone for stealing and they were hanged, you got a reward of forty pounds. Or so the law said. Molly had never heard of anyone actually getting the forty pounds, Hesper was willing to keep trying.

She was about Molly’s age but a little taller, with hair that might be blond under the dirt. She had the narrow, knowing eyes of an old criminal, and a cutthroat’s face, carefully schooled to show no expression. When Hesper saw Molly looking at her, she sneered and spat on the ground.

And who was this old biddy on Molly’s other side? She was ancient, at least thirty years old, her stringy hair graying and her sallow skin deeply scarred by smallpox. Molly had seen her around Bartholomew’s Fair, selling handkerchiefs that weren’t her own. That old woman looked very likely to be fruit for the Deadly Nevergreen Tree, as they called the gallows at Tyburn.

The woman looked at Molly and smiled reassuringly.

Over in the corner, a bailiff was stirring the coals to keep the branding iron hot. Was someone going to be branded soon, or was he just making sure the fire stayed lit? Molly could smell the coal smoke from where she stood, but she couldn’t feel the heat. It would be nice to get close enough to that fire to warm her aching fingers and toes. But not too close. Molly felt dizzy with cold, and with hunger. She hadn’t eaten since the day before yesterday.

A gentleman was making his way across the yard, a nib cull who clearly didn’t belong in the Old Bailey. He was dressed in pearl-gray velvet knee breeches and a matching velvet coat. Molly wondered what he was doing here. He stopped a bailiff and began talking to him, gesturing once in Molly’s direction. She thought she had seen him somewhere before.