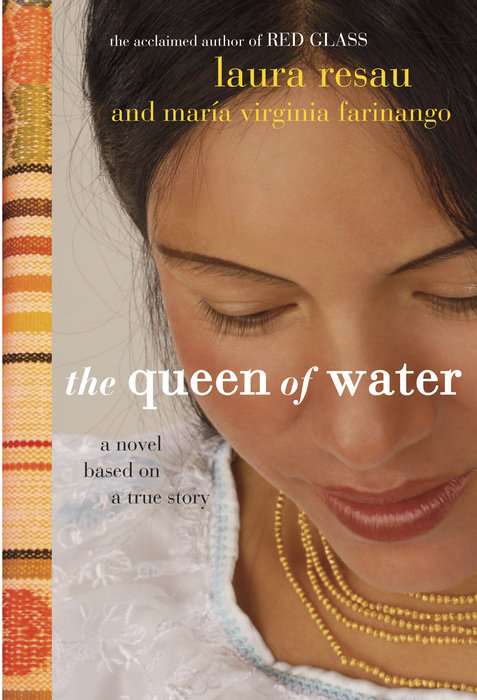

The Queen of Water

For fans of I Am Malala comes this poignant novel based on the true story of one girl's unforgettable journey to self-discovery.

*An ALA Amelia Bloomer Selection*

*An ALA-YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults Book*

Born in an Andean village in Ecuador, Virginia lives with her family in a small, earthen-walled dwelling. In her Indigenous community, it is not uncommon to work in the fields all day, even as a child, or to be called a longa tonta—stupid Indian—by members of the privileged class of mestizos, or Spanish descendants. When seven-year-old Virginia is taken from her home to be a servant to a mestizo couple, she has no idea what the future holds.

In this poignant novel based on her own story, the inspiring María Virginia Farinango has collaborated with acclaimed author Laura Resau to recount one girl's unforgettable journey to find her place in the world. It will make you laugh and cry, and ultimately, it will fill you with hope.

An Excerpt fromThe Queen of Water

Chapter 1

Before dawn, I wake up to the sound of creatures scurrying inside the wall near my head. Mice and rats and dogs have burrowed these tunnels through the dried clay, searching for food scraps. I'm always searching for food scraps too. Right now my belly's already rumbling, and it's hours till breakfast.

The house is dark as a cave except for bits of blue light coming through the holes in the earthen walls. My gaze fixes on a new trail of golden honey oozing from a crack, just within arm's reach. Bees live in there, black bees that sting terribly, but make the best honey in the world. I poke my hand in the crack and scoop out the sticky sweetness and lick it from my finger. It's gritty but good.

Our guinea pigs are hungry now too, squeaking and dancing around in their corner, waiting for alfalfa. I can see every corner of our house from my sleeping place on the floor. Mamita and Papito are snoring under their wool blanket on a bed frame made of scrap wood. My brother and sister are curled up next to me--Hermelinda on the end and Manuelito wedged in the middle--and the fleas and bedbugs and lice are crawling wherever they please. My spot against the wall is cozy, the perfect place for licking honey in secret.

Soon Mamita will awaken, standing up and stretching in her white blouse that hangs midway down her thighs. Then, yawning, she'll wrap a long dark anaco around her waist, golden beads around her neck, and red beads around her wrists. Then she'll open the door and a rectangle of misty morning light will shine into our house's musty darkness. Then she'll light the cooking fire and we'll all slurp steamy potato soup around the fire pit.

If she catches me with honey dripping from my fingers, her face will twist into a frown. When people tell her, "Your little Virginia is vivisima!" Mamita snorts, "Humph, she's clever for stealing food, that's about all."

It's true, I do use my wits to fill my belly with fresh cheese or warm rolls. Or to get something I really want, like a pet goat or a pair of shoes. But there's more. I have dreams. Dreams bigger than the mountaintops that poke at the clouds. In the pasture, I always climb my favorite tree and shout to the sheep, "I'm traveling far from here!" and my tree turns into a truck and I ride off to a place where I can eat rice and meat and watermelon every day.

In the half-light of dawn, I plunge my hand deeper into the darkness inside the wall, searching for honey, dreaming, as always, of golden treasures.

After breakfast, I'm in the valley pasturing sheep under a sky the dull gray of cow intestines, when Hermelinda appears on the hill. I squint up at her. The mountains loom behind her, peaks lost in heavy clouds. She waves her little arms at me, the wind whipping her hair in all directions. "Virginia!" she cries in her squeaky toddler voice. "There are mishus at the house. Mamita says to come right away!"

Mishus are what we call the mestizos. It's a mean word, in the same way that their names for us--longos, or dirty Indians--are mean. With my golden goat, Cheetah, at my side, I climb toward home, urging the straggling sheep along with my stick. Feeling suddenly sick, I call out, "Hermelinda, which mishus?"

"Alfonso and his wife and two others."

I stop in my tracks. Alfonso owns the land my family farms. Lately, he and his wife, Mariana, have made a point of talking to me whenever they visit the fields, asking me questions, eyeing me up and down, then murmuring to each other as they walk off. Alfonso is the one who took my cousins Zoyla and Gregoria away from their parents two years ago. Zoyla and Gregoria and I used to play market together while we pastured the animals. And then, one day, when they were near my age now--about seven--they left with the mishus.

We never heard from them again.

I head up the path, pushing against the crazy wind, kicking at rocks and smacking trees with my stick as I walk. Past the corn and potato fields, my house comes into view, looking small and weak against the mountains towering behind it. I can make out the forms of the mishus sitting on the dirt patio with my parents. My muscles are tensing, the way they do when I see dogs in the distance and I'm not quite sure if they're nice or mean.

I'm grateful Cheetah is at my side. Even though she's only a goat, she loves me more than anything in the world. And she'll do anything to protect me. Once, when a vicious dog tried to attack, Cheetah hurled herself in front of me and rose to her hind feet. "Maah maaah!" she bellowed in its face, slashing the air with her front hooves. The dog had never seen such a brazen goat, and it backed away, bewildered. It's good to have someone love you so fiercely. Even if that someone is a goat.

I rest my hand on her honey brown head and rub her ears, walking slowly, my heart thumping. As I lead the sheep into their pens, I watch the patch of weeds in front of our house where Alfonso sits beside his wife with her ridiculous, huge bun, along with a thin mestizo man. A fat mestiza woman with short hair and a polka-dot dress sits a little off to the side. I take a deep breath, then head toward them, brandishing my stick like a machete. The closer I walk, the hotter my face gets, as though my blood has caught fire.

Mamita is watching the mishus politely as Papito chats with them, his face unusually friendly. As I come closer, Mamita looks up at me and frowns. Her glare orders me to stop swinging my stick and behave.

But I look straight ahead, ignoring them all, and, still swinging my stick, stomp straight into the house.