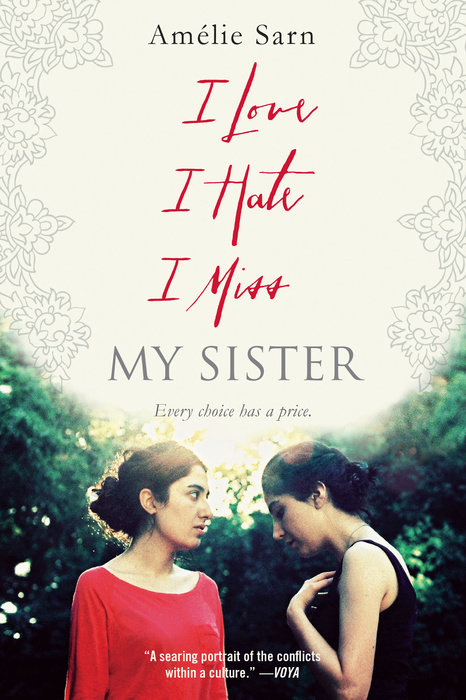

I Love I Hate I Miss My Sister

For readers of The Tyrant’s Daughter, Out of Nowhere, and I Am Malala, this poignant story about two Muslim sisters is about love, loss, religion, forgiveness, women’s rights, and freedom.

Two sisters. Two lives. One future.

Sohane loves no one more than her beautiful, carefree younger sister, Djelila. And she hates no one as much. They used to share everything. But now, Djelila is spending more time with her friends, partying, and hanging out with boys, while Sohane is becoming more religious.

When Sohane starts wearing a head scarf, her school threatens to expel her. Meanwhile, Djelila is harassed by neighborhood bullies for not being Muslim enough. Sohane can’t help thinking that Djelila deserves what she gets. But she never could have imagined just how far things would go. . . .

An Amelia Bloomer Project List Selection

A CBC Notable Social Studies Trade Book of the Year

A Bank Street Best Book of the Year with Outstanding Merit

"Sarn’s poignant novel surely raises issues of religious freedom, but it is foremost a coming-of-age story about personal choice and the uniquely powerful bond between sisters."—The Horn Book Magazine

"[A] moving story, which provides rich material for conversation about family relations, religious identity, and civil liberties."—Publisher's Weekly

“Thought-provoking.”—Kirkus Reviews

"Important and timely."—Booklist

"In seamless chapters transitioning between present and past, this short, fast-paced, tragic story contrasting two clearly drawn Muslim sisters explores similar contemporary cultural and religious issues portrayed in Randa Abdel-Fattah’s Does My Head Look Big in This?"—School Library Journal

“A fair and balanced look at not just two equal and opposite perspectives on these issues, but at the multiple, refracted, messy nuances in between.”—The Bulletin

“A searing portrait of the conflicts within a culture.”—VOYA

“Sarn writes with concise, timely insight about culture, religion, and politics, but what lingers most is the powerful bonds of sisterhood.”—smithsonianapa.org

An Excerpt fromI Love I Hate I Miss My Sister

“Sohane, can I borrow your jeans?”

“No, I already told you, Djelila.”

I don’t feel like lending Djelila my jeans again. Not that I want to wear them, because I don’t. Ever since the last time Djelila borrowed them and I saw how much better they fit her, I no longer feel like wearing them.

“Come on, little sis, please.”

“No. And I’m not your little sis. I’m a year older than you, remember?”

“Sohane . . .”

I roll my eyes. Djelila isn’t giving up. I know she’ll soon come and sit beside me, ask me what I’m reading, get up to tell me all about the incredible shot she made from the middle of the basketball court in one of her dreams last night. She’ll pretend to focus, bend her knees, throw an imaginary ball, put on a dazed look as she explains that the ball is rolling around the rim of the basket; then she’ll burst out with a whoop when, at last, it falls in, adding the three points needed for the win.

“The referee whistles the end of the game!” she’ll shout. “And the crowd stomps onto the court and lifts me up on their shoulders. Coach Abdellatif congratulates me and declares that I am the best player of all time; the college recruiters are here to watch me. . . .”

And she will manage to make me laugh.

My sister is beautiful.

Very beautiful.

Djelila has fine features, soft and silky skin, not one spot of acne. She is tall, her smile and her dark eyes radiant. She’s wearing only a T-shirt, a pair of shorts, and high-tops. Her thighs are long and muscular, her legs, as always, perfectly smooth.

Lending her my jeans is out of the question.

“Tell me, Sohane, what do you think of Jeremy?” she asks.

Just as I predicted, Djelila comes to sit beside me. We’ve always shared a bedroom. All of my memories include her. I love no one else more than my little sister and I hate no one else as much.

“Who’s Jeremy?”

“The guy in twelfth grade.”

“Oh, him. Well . . .”

“Is that all you have to say? He’s as handsome as a god.”

“Don’t talk that way, Djelila. You know I don’t like it.”

Djelila laughs. “Sorry, he’s killer handsome. Is that better?”

I would rather not answer. Djelila talks the way she wants to; that’s her problem. But I don’t have to listen to her using the word “god” so casually.

“Don’t give me that disapproving look,” Djelila says, smiling as she scoots closer. “Tell me what you think of Jeremy.”

I put down my book on the night table that separates our beds. The room is small.

“Why do you ask? Does he want to go out with you?”

Djelila shakes her head. “I noticed him at the gym the other day, after practice,” she says. “I think he’s on the handball team. I couldn’t stop staring at him, but he didn’t even look at me.”

“And that’s what’s bothering you?”

“No. I like him. That’s all.”

“You don’t even know him.”

“Well, I like him anyway.”

“You’re going to get into trouble again, Djelila.”

Racine High School is on the outskirts of our housing project. It’s a large complex composed of five buildings swarming with 2,153 students, grades eleven through twelve, plus three vocational divisions. I’m in twelfth grade; Djelila is in eleventh. At school, we go unnoticed. It’s as if we lead another life. As if we have multiple personalities--one for our parents, a second for the projects, and a third for high school.

Unfortunately, the partitions are sometimes fragile.

Djelila already learned this the hard way.

“Do you mean Majid and his gang?” Djelila says. “Whatever. I’m not afraid of them! They’re a bunch of losers with nothing better to do than sit on the project benches and spy on us. They’re jealous, that’s all. Because we’re happy!”

I am not going to remind her that two days ago I found her crying in front of the elevator. Her mascara had run around her eyes. I’m the one who told her to calm down, not to let those lowlifes get to her, just to let them spit their venom. “Ignore them, that’s the best thing you can do,” I said.

In the elevator, Djelila put her head on my shoulder and I wiped off her mascara with a tissue. She whispered, “Thank you.” When we entered our apartment, she went directly to the bathroom to clean her face, then came out and joined Mom in the kitchen; I went to our room to do my homework. From there, I could hear the two of them laughing.

Dad’s voice intrudes on my thoughts.

“Girls, dinner’s ready,” he says.

He knocks on the door and walks off. He never comes into our room. He would never even think of opening the door. As if he’s afraid of what he might see. This amuses Djelila. On purpose, she’ll ask our mother, right in front of him, if she has seen these underpants or that bra. “You know, the pink one with double straps? I can’t find it,” Djelila will say. She thinks it’s fun to see Dad stiffen over his newspaper, pretending that he doesn’t hear a thing.

“A girl’s space must stay a girl’s space,” he explains to our little brother Taieb, who listens wide-eyed. “Women have secrets that we don’t need to know about. We must respect their privacy.”

Taieb doesn’t understand. All he wants is to barge into our room and play with us. Actually, because Dad forbids it, it allows us to have some peace.

A slip of paper is shoved under our door. Someone scribbled on it with a purple felt marker: Dinner is reddy. It’s Idriss’s handwriting. He’s in first grade, a few years younger than Taieb, and spends all his time writing even though he hasn’t started to learn spelling yet.

I push Djelila away and get up.

“Come on, let’s go have dinner,” I say.

Djelila rises, smiling, kisses my cheek for no good reason, and puts on her old pajama pants, the same ones she has worn for at least two years. Softly she walks toward the door, laughing.

She is beautiful, my sister.

I envy how she is so carefree.