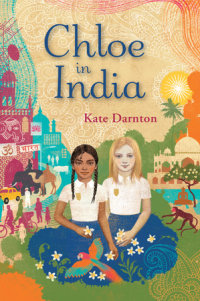

Chloe in India

A poignant and delightful story involving class, race, social customs, and a unique friendship that questions them all.

Though they’re divided by class, language, appearance—you name it—Chloe and Lakshmi have a lot in common. Both girls are new to Class Five at Premium Academy in New Delhi, India, and neither seems to fit in. But they soon discover how extraordinary an ordinary friendship can be and how celebrating our individuality can change the world.

"Whether describing the heat of a Delhi summer or the emotions of a homesick preteen in a strange land, Darnton gets the details right, bringing characters and story to life and also educating readers about the economic discrepancies rampant in India. Blonde American Chloe's perspective gives Western readers a way into this tale of inequality in a foreign culture."--Kirkus

"A solid multicultural offering for middle grade collections."--SLJ

"The heart of the story—standing up for others, despite social or economic class—can offer a good discussion for readers and hopefully get them thinking about those around them."--Booklist

"An informed and informative work of fiction that incorporates eye- opening facts about poverty and social systems outside of the United States while never losing the protagonist’s authentic and relatable voice. Evocative in setting, sympathetic in character, and noble in intent, this story is for armchair travelers and seekers of fairness and friendship."--The Bulletin

An Excerpt fromChloe in India

Chapter 1

I was so busy I didn’t hear Mom come up behind me. I heard her voice before I saw her, and this was what that voice said:

“Chloe, Chloe! Oh no, Chloe!”

I froze in front of the bathroom mirror. In my left hand, I was holding a clump of blond hair away from my head. Well, hair that used to be blond. Now it was After Midnight Black.

In my right hand, I was holding an After Midnight Black permanent marker.

“Now what have you done?” Mom groaned.

This, I knew, was a rhetorical question--one of those questions grown-ups ask but you’re not really supposed to answer.

Besides, it was pretty obvious, no? The evidence was all there: black marker, black hair.

My mom is a watchdog journalist, which does not mean that she watches dogs and then writes about them. It means she investigates stuff. You’d think she’d be able to figure this one out by herself.

“Why, oh why?” Mom wailed.

Now, that was a trickier question. To be honest, I hadn’t given the whole thing much thought. It wasn’t like I was going to color my whole head with Magic Marker. But maybe, if I colored one little section right at the front, then looked in the mirror with my head tilted at just the right angle, I could see what I’d look like with all-black hair.

“What were you thinking?” Mom moaned.

Here is what I was thinking:

Every single one of the ninety-eight other kids in Class Five at Premium Academy has black hair. Every single one. In fact, there is only one other girl in the whole school with blond hair, and I’ve seen that girl sitting alone in the senior school stairwell picking at her split ends. I think she’s from Germany, which might be even worse than being from America.

I didn’t want other kids to mix me up with the split-end-picking, stairwell-sitting blond girl, so I had decided to rectify--which means fix--the situation.

(For the record, I am eleven, but I like to use big words, mainly because I read a lot. It’s one positive side effect of being new and not having any friends.)

Mom had her hands on her hips, eyes all googly. Her lips were clamped into a tight, thin line. It seemed like she was waiting for me to say something.

So I did.

“Well, you’re the one who brought us here,” I said.

It wasn’t me who decided to move our whole family from Boston, Massachusetts, to New Delhi, India, over the summer. My parents decided that. Well, mainly my mom. “It’s where the stories are,” she had said by way of explanation. I was only ten back then, and I got this picture stuck in my head--the streets of India lined with storybooks. Literally. Madeline and Eloise and Pierre (you know, the boy who says, “I don’t care!”) were lined up like lampposts along a busy street. Elephants wandered in and out among them. That was what India would be like--elephants and stories everywhere.

Boy, was I wrong. They don’t even have a decent public library here. As for elephants, we hardly ever see them. When we do, it’s one sad elephant trudging down the hot highway to some fancy kid’s birthday party. A mahout sits on its neck, his bony knees tucked tight behind the elephant’s ears. He beats the elephant with a stick. Cars and buses honk: Out of the way, you dumb elephant! Out of the way!

Back in Boston, we lived in a tall, narrow brick building attached to other tall, thin brick buildings on both sides. Ours had big windows with black shutters that looked like ears. Huge maple trees lined both sides of our street. The trees were so tall, their leaves met at the top to form a canopy. In the summer, it was like living under a bright green tent.

Our street in Boston was a dead end, so even though we lived smack in the middle of the city, there were hardly any cars and we kids were allowed to play by ourselves out on the stoop. Sometimes we’d sneak white pebbles from the neighbors’ Japanese garden and roll them down the steps to see how far they’d make it out into the street. Our building didn’t have a yard, but that was okay because there was a city park right around the corner, with a playground and a tennis court and a hill that we would sled down in the winter.

Here in Delhi, we have a park across the street too, but the playground is just a broken seesaw and a metal slide that gets so hot you could fry an egg on it. There’s the skeleton of a swing set with chains where the swings should be. The chains dangle there, swaying in the wind. Sometimes street kids tie rags to their ends to make seats, but the rag swings last only a day or two before they fall apart. As for sledding, ha! The ground is flat as a pancake. And it never, ever snows.

The movers showed up at our apartment in Boston on June 13. I remember the date because it was the day after my birthday, the day after I turned eleven. Mom gave them slices of my leftover cake. I watched them through a crack in the french doors. I watched them eat up all that cake, scraping the last bits of fudge frosting from their paper plates with my purple plastic birthday spoons. Then they packed all of our stuff into brown cardboard boxes and loaded the boxes and all of our furniture into a big orange truck and drove the truck to Cape Cod, where they unloaded everything into Nana and Grandpa’s basement. Mom and Dad knew we wouldn’t be staying in India forever, so they thought renting furniture was a much better financial decision--their words, not mine--than paying to cart it across the ocean. Back at our house, there was nothing left but dust bunnies and seven enormous suitcases. That was part one of moving.

Then we all got on an airplane: Mom and Dad and Anna, who was fourteen, and Lucy, who was a tiny little baby, and me and the seven suitcases. After a very long time, we got off in Delhi. That was part two.

And now a different family lives in our skinny brick building in Boston. A different kid sleeps in my room, while I . . . sleep in India.

Besides moving to India, here are some of the other things that I did not decide:

I did not decide to be a little sister.

I definitely did not decide to have a little sister.

I did not decide to go to an Indian school where I would be the only kid (okay, besides the split-end-picking, stairwell-sitting German girl) who is blond. Oh, and American. I am the only kid (besides Anna) who is American.

All of these things just happened to me.

My mom looked at her wristwatch: 7:15. We were going to be late for school. Again.

She let out a loud sigh. “Let’s clean you up,” she said.

Chapter 2

By the time I got down to the car, Anna was sitting in the backseat, her seat belt fastened, her arms crossed tightly against her chest and her face scrunched up in a scowl. Her uniform was perfectly neat: tan shirt, navy skirt, navy belt, tan socks with navy stripes. There was no mud caked around the soles of her black nylon school shoes. There was no gunk from peeled-off star stickers on her shiny brass belt buckle. A navy elastic held her long, straight brown hair up in a high, tight ponytail. Her new badge--ANNA JONES, UNIFORM MONITOR--was clipped onto her left breast pocket.

Ever since Anna was appointed to uniform patrol, she’s been on my case.

“Your socks don’t match!”

“Your skirt is too short!”

“Ew, is that dal? Is that yesterday’s lunch on your shirt?”

Today was no different. “We are all supposed to cooperate when Dad’s away on business trips, Chloe. Mom needs our help. Instead, you’re making us late!” Anna glared at me. Then she gasped: “What happened to your hair?”

I looked out the window, pretending to see something really interesting instead of the plain old whitewashed wall that surrounds our house.

“We are ready, girls?” Vijay, our family driver, grinned at me in the rearview mirror.

I love Vijay. Even though his entire job is to drive us around all day--a job that Mom says would make her positively cross-eyed crazy--he’s always in a good mood. When Mom isn’t in the car, he plays bhangra music really loud. Sometimes he sneaks us toffees. And every couple of months, he dyes his hair electric orange with henna.

I nodded. Vijay pressed his palms together in a two-second prayer and then pulled the car out into the street.

“What happened to your hair?” (Anna again.)

I hummed a little before answering. “Oh, this?” I finally said, making my voice all normal-sounding. “It’s my new hairstyle. Mom and I decided to give me a trim. I like it.”

But here’s the truth: I did not like it.

To get rid of all the black and then even things out, Mom had to cut off the whole front part of my hair right up by the roots. Just thinking about it reminded me of the cold kitchen shears against my forehead, the ripping sound of my hair being cut. Long, limp blackened strands had fallen to the bathroom floor and curled up there like dead centipedes.

Now my bangs were so short, they stuck up from my scalp like the bristles of a hairbrush. When I had looked in the mirror, the first thing that crossed my mind was Porcupine. I look like a porcupine.

The second was I look really, really ugly.

I might have cried a little bit.

Anna giggled. “You look like Lucy.”

“I do not !”

Lucy is one and a half, and her white scalp shows through short tufts of reddish hair. She is practically bald.

“You do! You look like a baby!”

I crossed my arms over my chest. “Well, Mom says it’ll grow out in a month or two, which means I’ll be back to normal soon.”

“So you don’t like it after all,” Anna crowed. “You said you like it, but really, you don’t.”

This is one of the most annoying things about Anna--she’s always trying to trip me up, trying to catch me saying something that isn’t technically one hundred percent true.

But it isn’t the absolutely most annoying thing about Anna. The absolutely most annoying thing about Anna is that she was born first, and so every year, year after year, she is exactly forty-two months older than me. Anna will always be older, which means that she will always know more things and be better at most things than me.

No matter what I do, I will never catch up to Anna.

As if we weren’t late enough, the car got stuck at the red light near school. I know the spot really well because it’s the only red light and so all the cars and scooters and auto-rickshaws and bikes and buses--and often a bunch of lost-looking cows--squish up against each other, everybody pushing and shoving to make the turn. There’s a small market on one side where the rickshaw drivers double-park, blocking half a lane of traffic as they chew paan, pick their noses, and wait for fares. We get stuck there pretty much every morning.

Anna likes to do flash cards on the way to school, but I like to look out the window and watch the world go by. Next to the market there’s a small slum built right up to the edge of the road. As the car idled, I watched some men who were squatting in a circle, sipping their morning chai out of tiny plastic cups just like the ones at the dentist’s office back in Boston. One guy was cleaning his teeth with a twig. There was a group of teenage boys too, piling carts high with bright green limes, and an old woman with a face like a charred marshmallow, sitting on a charpoy, picking lice from a little girl’s hair. When the girl squirmed, the woman slapped her on the side of the head and went back to picking. There were three goats tied up next to them. Then a little kid pulled down his shorts and squatted right next to our car, getting ready to push out a poop. I looked away. Yuck.

Click.

With the flick of a finger, Vijay locked the car doors.

A beggar was winding his way through the cars, coming toward us. He was old and dressed in rags, with a walking stick and no shoes. At first I tried to smile at him, but then he put one hand up on the glass, right in front of my face. He had stumps instead of fingers. Vijay pulled the car up a few inches.

That was when I saw the girl. She was stumbling across the intersection, carrying a large plastic jug of water in each hand. She wore flip-flops and a pink lehenga smudged with dirt. Her shoulders sagged from the weight of the jugs, which bumped against her shins as she walked, splashing water on her skirt. She had to be younger than me. Maybe eight?

As she crossed the intersection, she got so close to our car, I could see the hole in her nostril where a nose ring used to be. The auto-rickshaw next to us inched forward, trying to cut her off. The driver honked and yelled but the girl didn’t look up.

When she reached the other side, she ducked down a narrow alleyway into the slum. The pooping boy and the beggar had vanished, so I pressed my face back against the window, trying to follow the girl with my gaze. Where was she going? Why wasn’t she at school?

The light turned green.

“I wonder what Anvi will think of your new favorite hairstyle,” Anna said. Her fingers were still flipping through her flash cards, but her eyes flicked over to me for a second.

Anvi Saxena is the girl I most want to be friends with at Premium Academy. She has long, straight black hair and really long arms and legs. She’s like a spider. Not an icky spider but an elegant one. Her uniform is always perfect, like Anna’s. But in Anvi’s case, it’s because all her clothes are brand-new. She once told me she has thirteen uniform skirts and eighteen uniform shirts. To give you some perspective, Anna and I have three of each.

Anvi is popular, which means a lot of people like her, but even I can tell she’s pretty spoiled.