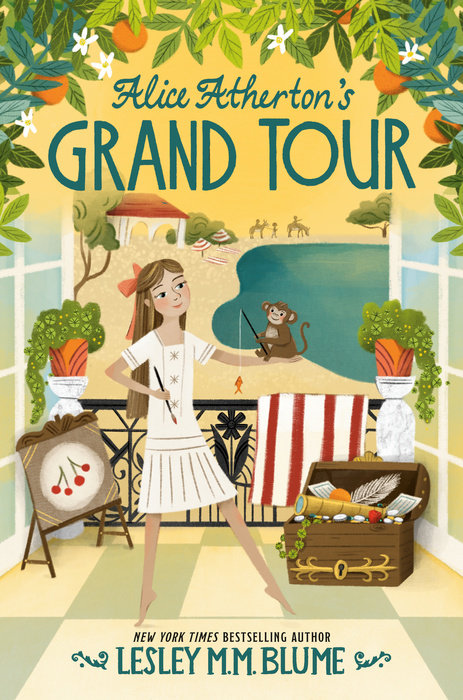

Alice Atherton's Grand Tour

The heartwarming story of a young girl sent to live with the extraordinary Murphy Family in southern France.

Ten-year-old Alice Atherton is sent by her father to spend the summer with his dear friends the Murphys who live with their three children and pet monkey in the French Riveria. There, Alice will meet and learn from some of the most extraordinary luminaries of the time. She visits a junk yard with Pablo Picasso looking for objects to make into art, performs a dance inspired by celestial bodies with the renowned Ballet Russes, and imagines magical adventures with Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

An uplifting story that will appeal to readers who love books by authors like Kate DiCamillo and Jeanne Birdsall.

An Excerpt fromAlice Atherton's Grand Tour

Chapter One

The Right Cure

New York City, 1927. Alice Atherton looked out the window at the park across the street from her house. A light, pretty snowfall was turning the park’s bushes and benches into white-hided, slumbering animals. Dusk was falling too.

Alice would have given anything to be outside in that snow, but instead she was stuck inside, subjected to an endless geography lesson by her governess, Miss Pennyweather. Alice secretly called her Old Miss Pennyweather, even though the governess probably wasn’t all that old. She just happened to be gray in both face and spirit, and could make any subject under the sun impossibly dull. Old Miss Pennyweather could probably rob a bank and all of the tellers would fall asleep from boredom during the holdup.

Today’s grueling lesson was taking place in the parlor. A roaring fire in the fireplace made the room hot and dry. Alice’s cheeks burned pink and her head swayed from drowsiness.

“Cairo is an exotic city full of elaborate lore and mythology,” Old Miss Pennyweather droned on. “But in ancient times, Alexandria was the true cultural capital of Egypt.”

Here she paused.

“Alice, please point to Alexandria on this map.”

But Alice did not point to Alexandria on the map. In fact, Alice did not even hear Old Miss Pennyweather’s instruction. This is because she had fallen into a deep, rather sweaty daydream. In her mind, Alice had left the parlor minutes earlier and was out rolling around, like a happy dog, in all of that snow across the street.

“Alice Atherton!” exclaimed Old Miss Pennyweather, dropping a book on the floor with a rude bang. “Wake up this instant.”

Swooning, Alice opened her eyes and looked blearily at her governess.

“Alice, this is the third time I’ve had to chastise you this afternoon,” Old Miss Pennyweather thundered. “This is most regrettable behavior. Are you unwell?”

“I don’t know,” Alice muttered. “I’m just sleepy.”

Old Miss Pennyweather swept over to Alice and clapped her papery hand onto the child’s forehead.

“You may indeed be a touch warm,” she said. “Oh dear, oh dear--what if it’s the influenza? I’m certain that it’s lingering in this filthy city. Or mumps? Or--God help us--scarlet fever?”

Old Miss Pennyweather bustled Alice out of the parlor and up the stairs into her bedroom.

“Mrs. Millicent,” she called, summoning the housekeeper. “Bring a bowl of cold water at once. Send for the doctor. And please tell Mr. Atherton that Miss Alice has taken ill.”

Old Miss Pennyweather shoveled Alice into her bed. Soon a large bowl of cold water materialized, and by the time the doctor arrived a few minutes later, Old Miss Pennyweather--perhaps inspired by her lecture on Egypt--had practically made Alice look like a mummy, swaddled in bands of chilly, wet towels.

The doctor listened to Alice’s chest with his stethoscope. He peered into her ears, eyes, and throat.

“Oh dear, Doctor,” fretted Old Miss Pennyweather. “Please tell me that it’s not the same terrible fever that took this child’s mother six months ago. This house simply can’t have another tragedy.”

The doctor began packing up his equipment into a little leather bag. “I think, Miss Atherton, that you are going to live,” he said to Alice kindly.

“You’ll be relieved to learn that there isn’t a blessed thing wrong with her,” he told Old Miss Pennyweather as he stood up. He felt a bit grumpy with the governess, as he had left behind a delicious dinner of roast beef and gravy to rush to Alice’s bedside. That dinner--which had been hot and jolly just half an hour earlier--was now likely sitting there back on his dining-room table, cold and congealed.

“Well, thank heavens,” exclaimed Old Miss Pennyweather. Sensing the doctor’s annoyance, she shifted to self-defense: “One can’t be too careful in this day and age: germs lurk everywhere.” She apologetically ushered the doctor out the bedroom door.

Left alone at last, Alice lay in bed and stared out the window. It was now dark outside--a lovely, deep, inky blue darkness--but Alice could still see the snow falling.

Alice’s mother had loved winter. She had loved fur muffs and stocking caps and mittens and boots. She had loved sleigh rides and Christmas and snowy walks through the park. She had even loved eating snow, although it had appalled Alice’s father when she did it.

“Time passes more slowly in winter--did you know that?” she had once told Alice as they rode down Fifth Avenue in their horse-drawn carriage, snuggled together under a blanket.

“That’s silly,” said Alice, happily breathing in her mother’s perfume. “Time goes at the same speed in every season.”

“No, no--it’s absolutely slower in winter,” insisted her mother. “And that’s why it’s my favorite season, because it also means that you, Alice, are growing more slowly during those months. I get to have you as my little girl for just a bit longer.”

Alice felt the reverberation of the heavy front door closing as the doctor was sent back to his supper. Then, a few moments later, she heard muffled voices coming from her father’s study, which was on the floor below her room. Alice peeled off the clammy mummy rags, tiptoed to the stairwell, and eavesdropped.

Old Miss Pennyweather was holding a conference with Alice’s father, Mr. Atherton.

“What did the doctor say about her condition?” Mr. Atherton asked the governess.

“That there is nothing physically wrong with her,” replied Old Miss Pennyweather. “But there clearly is something wrong with her. She appears to be sleepwalking through the days. Nothing interests her at the moment. She barely eats. She has been like a different child since Mrs. Atherton passed on, sir. I know that she’s grieving, but to have no interest in life at all anymore?”

The grandfather clock ticked in the downstairs foyer. It had been draped in a black velvet shroud since Alice’s mother had died. Alice knew that her father was smoking his pipe and listening and thinking, and when he was pipe-smoking and listening and thinking, he could never be rushed to answer.

“This has indeed been an exceptionally difficult period for all of us, Miss Pennyweather,” said Mr. Atherton at last. “And clearly none of us here have the solution for how to help Alice. Neither the doctor, nor I, nor you.”

There was another moment of silence.

“Let me give the matter more thought,” Mr. Atherton said eventually. “I believe that we need a creative solution, perhaps something even a bit unconventional.”

Alice imagined Old Miss Pennyweather’s response to this: she probably looked like she’d just tasted an especially sour lime. The mention of anything unconventional was repellent to her.

The governess retreated from the study and began to climb the stairs. Alice scuttled back into her room, dove into her bed, pulled up the covers to her chin, and squeezed her eyes shut. Her governess peeked in and, thinking that Alice had fallen asleep, left again in relief, closing the door behind her quietly.

Alice waited until she heard Old Miss Pennyweather’s footsteps climb the stairs to her room on the top floor. She reached over to her bedside table and picked up a small gold brooch that had once belonged to her mother. The shape of a bunch of lilies of the valley, the brooch had flowers made of small pearls. Alice pinned it to the collar of her nightgown and tiptoed downstairs to her father’s study. There she stood timidly in the doorway and gazed at him.

Mr. Atherton wore thick glasses. He was the president of a publishing company, and over the years, his eyes had grown tired from reading millions and millions of words. Bookshelves lined his study walls from floor to ceiling, and dozens of books stood in tall, crooked stacks all around the room.

“Hello, Papa,” Alice said quietly.

Her father looked up from a manuscript that he was reading.

“Come in, little goose,” he said.

Even though Alice was relatively tall for a ten-year-old, she climbed up onto her father’s lap and nestled her head onto his shoulder. He touched the lilies-of-the-valley brooch on her collar, and gave her a gentle kiss on the top of her head.

“Are you feeling better?” Mr. Atherton said, smoothing down her hair. “Miss Pennyweather was in quite a state this evening.”

“I was just tired,” Alice told him.

“Why are you so tired?” her father asked her. “Aren’t you sleeping well at night?”

“It’s not that,” she told him. “I’m just always sleepy right now. And not just when Miss Pennyweather is being boring in our lessons.”

Mr. Atherton smiled. “Well, she does her best,” he said. “Although I know that she’s no substitute for your mother.”

“No,” Alice replied, and now she pressed her face against her father’s chest so he couldn’t see her crying.

Mr. Atherton smoothed Alice’s hair until her breathing became calm and even again.

“Little goose, I know how difficult things have been since your mother died,” he said a few minutes later. “I have been thinking tonight about how to help you. At first, I thought that keeping up your familiar routine here at home would be best. We’d already had so much change. But now I’ve come to the conclusion that the solution to your great unhappiness likely does not lie in this house. There is still too much sadness in it, and I think that you need lightness--and life.”

Alice had no idea what he meant, but she tilted her face up and looked at him while he talked.

“I have just had a rather unusual idea,” Mr. Atherton said. “But it would involve an adventure.”

“Would you be coming along on the adventure too?” asked Alice.

“I wish I could,” he told her. “I can’t leave my work here in New York, and anyway, this journey is one that will be given to you by someone else.”

“So the adventure is outside New York, then?” Alice pressed.

“Yes, but of course I would ask Miss Pennyweather to accompany you,” replied Mr. Atherton. “It might seem at first like a big undertaking, but I feel certain that this adventure would be life-changing--and full of happy surprises. Do you think that you could be open to the idea?”

Alice was growing curious. “Where would I be going?” she asked her father.

“It’s a secret--for now,” he told her. “Do you trust me?”

Alice thought for a minute. She didn’t like the idea of being away from her father, but she did like the idea of happy surprises and lightness and life. Her mother had always said yes to adventures. So perhaps Alice should too. She nodded at her father.

“I’ll put things in motion tomorrow,” he told her. “Let’s see what happens.”

Early the next morning, a messenger came to fetch a telegram written by Mr. Atherton to some mystery recipient. A day later, the messenger returned with a reply. More telegrams were carted in and out after that, and then, finally, about a week later, Mr. Atherton called Old Miss Pennyweather and Alice into his study.

“Miss Pennyweather,” he said, “please have Mrs. Millicent arrange for our travel trunks to be taken out of storage as soon as possible.”

“What for, sir?” said Old Miss Pennyweather, who generally did not care for traveling more than three or four city blocks in any direction. The idea of foreign foods, foreign beds, and foreign toilets filled her with foreboding.

“I’m delighted to report that you will soon be departing for France,” Mr. Atherton answered. “To spend late spring and the whole summer with my dear friends Sara and Gerald Murphy, an American couple who live there, in their sun-filled, seaside house.”

He looked at Alice.

“When I was a young man, American parents of great fortune sometimes took their children on trips to learn about art and places and people all around the world,” he told her. “It was called a grand tour. While we are not people of great fortune, I can proudly send you on this different sort of grand tour, at Mr. and Mrs. Murphy’s home. Theirs is a magnificent, wondrous world. They knew your mother well, and loved her. And what’s more, they have three smart, delightful children around your age.”

Old Miss Pennyweather went pale. Her panic was now reaching a fever pitch.

“With due respect, sir, do you think this is the right cure for Miss Alice?” she asked. “After all, France is so very, very far away, and what if she should fall ill on the journey across the ocean, or worse, fall into the ocean, and--”

Mr. Atherton cleared his throat and looked sternly at the governess over the top of his glasses.

“Yes, Miss Pennyweather, I’m quite certain,” he said. “Sara and Gerald are the kindest and most nurturing people I know. Alice, your mother adored them, and they adored her.”

Mr. Atherton took Alice’s hands in his.

“You do need to know,” he told her, “that Mr. and Mrs. Murphy are not like anyone you’ve ever met before, and their friends are all very . . . well, unusual. Once again, I’m asking you: Do you feel brave enough for this adventure?”

But his eyes looked mischievous instead of solemn, and so Alice felt deep down inside herself that she was indeed brave enough--just as her mother would have been brave enough--and she told him so.

“That’s settled, then,” he said, and sat back and put his pipe into his mouth. Old Miss Pennyweather looked as though she’d just swallowed a putrid-tasting bug.

Three weeks later, Alice and the governess and their travel trunks found themselves churning east across the Atlantic Ocean on a massive transatlantic liner named, aptly enough, the HMS Sojourn.

As Mr. Atherton watched the ship pull out of the harbor, he felt a pang about sending Alice so far away, and dreaded the loneliness of their house back on Gramercy Park. But as he had assured Old Miss Pennyweather, he was indeed certain that the Murphys would be the right cure for Alice. To get over death, he believed, we need to be around life. After her mother’s death, Alice herself would have to learn how to be truly alive and love life again. While Mr. Atherton was not certain about many things in life, he was certain about this: Sara and Gerald Murphy and their friends knew more about the art of living fully than just about anyone else.

Chapter Two

Villa America

“Oh dear,” moaned Old Miss Pennyweather as their train swayed from side to side. “I think I am going to faint again. Alice, do ring for that beastly porter.”

Alice pressed a buzzer to summon the porter. Ten minutes later, the door to their car opened, and the train’s French porter stepped neatly inside. Alice liked him. He had a funny little mustache that curlicued away from his nose, and a skinny arrow of a beard that pointed straight down toward his shoes. Already he had been summoned four times to tend to Old Miss Pennyweather’s various ailments.