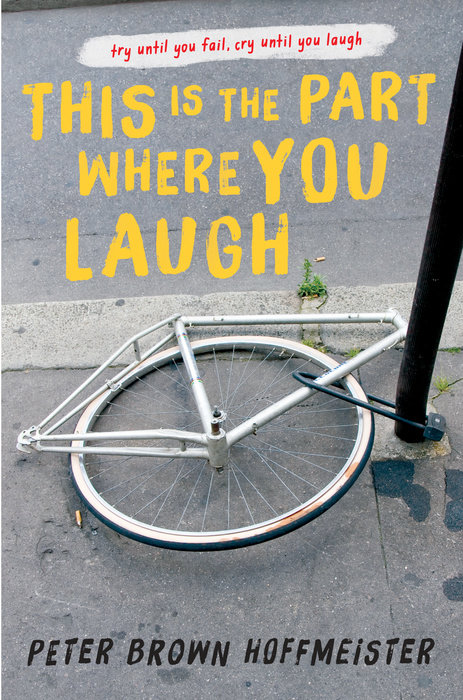

This is the Part Where You Laugh

"So real it hurts."—David Arnold, New York Times bestselling author of Mosquitoland.

A summer of basketball, first love, and the friends who've got your back when life gets crazy, set in a trailer park in small town America.

Travis never gives up.

Not when his mom takes off.

Not when he gets suspended from basketball.

Not when he cracks four ribs jumping off a bridge to impress a girl.

Not when he and his best friend Creature get into trouble deeper than they know how to handle.

From acclaimed author Peter Brown Hoffmeister comes a painfully-funny, sometimes-crushing story of growing up, making mistakes, and pressing on, against the odds.

"In my mind the best storytellers walk that high tight wire between tragedy and comedy. This Is the Part Where You Laugh is exactly the part where you laugh. And ache. This is a really good book!"—Chris Crutcher

"A courageous novel. Incandescent and unflinching." —Jeff Zentner, author of The Serpent King

"A raw offbeat novel with an abundance of honesty and heart." —Publishers Weekly, starred review

"Hoffmeister crushes it. There is blood and truth on every page." —Estelle Laure, author of This Raging Light

An Excerpt fromThis is the Part Where You Laugh

In the Mouth of the Crocodile

When it’s good and dark, I drag the two duffel bags to the edge of the lake. Out in front of me, smallmouth bass come alive on the surface of the water, and I wish I’d brought my fishing pole. But it’s good I didn’t--I don’t want to draw attention to myself.

One of the bags twitches.

Down the east side, there’s a series of wooden docks, all the same length, like gray piano keys jutting out into the lake. There’s no one out on any of the docks now. I double-check each one. Make sure I’m alone.

I slide the first caiman out of its bag, the rubber bands and duct tape still in place. The caiman doesn’t fight, so I start taking off the tape layers. When I get down to the big rubber bands around its mouth, I lean my forearm on its upper jaw the way the man showed me when I bought them. Then I take the final rubber bands off and jump out of the way.

The caiman opens its mouth and hisses, but it doesn’t move.

“Go,” I yell. “Get in the water.”

It doesn’t go anywhere.

I say, “Get.”

But it stays where it is and hisses at me.

I back away. Take the other duffel bag up the shore a bit, far enough to give myself a little room but still close enough to see the first caiman’s outline.

When I open the second duffel bag, I find that the caiman has wriggled free of most of its duct tape and rubber bands. It’s clacking its jaws and thrashing around in the bag like it’s trying to do a 360.

It whips its tail, and I say, “Whoa,” and zip the bag closed again, feeling lucky that I didn’t reach my hand in first. I step back and wait for the caiman to calm down.

After a minute, the bag goes still. I step forward, unzip it all the way, and jump back. The caiman fights and turns--flips the bag over before sliding through the opening and sidewinding toward me up the bank. The last piece of duct tape is still stuck to one of its back legs, keeping it off balance, a hitch in its step, but it’s coming at me anyway.

I sprint backward, duck under a branch, trip on a root, and fall on my face in the dirt. I scramble to my feet and grab a stick, spin around to defend myself, but the caiman’s not there. Not where I can see it.

I don’t know much about caimans other than what I read online after I saw the ad, but I do know that they love to hunt and can run 30 miles per hour. That quickness worries me. And their jaws.

I creep back toward the water, toward the bank, holding my stick, hoping I’ll see the caimans before they see me. But it’s dark now and I can’t tell what’s a log or a clump of grass, or a small crocodile. I creep forward. Now I’m close to the lake and I can’t see the first caiman, let alone the second. The duffel bags are out in front of me somewhere and the two caimans are there too, and I’m holding the stick and turning back and forth slowly, peering into the darkness all around me.

I planned on leaving no evidence, no sign that I was ever here, but I don’t want to get attacked either, and it’s dark now, and the reptiles are on either side of me.

I listen. Wait. Hunch down and look. But it’s too dark.

I back up, watching my footing, and keep backing up, scanning for shapes in the dark. I turn at the big tree, and I’m closer to the road now, and the streetlight comes on, a yellow slant over my shoulder.

When I get to my bike, I grip the handlebars and take one last look at the lake.

That’s for you, Grandma, I think, for your last summer here.

Because fuck cancer.

For My Grandma

Because fuck living in a manufactured double-wide in a trailer park after working hard her whole life as a teacher for not enough money, being disrespected by students and principals and school districts. Fuck being here in this trailer park and waiting to die.

Fuck cancer.

Because this will give her more entertainment than sitting in her room. This will give everyone along the lake some entertainment, something they need, something to talk about.

Retribution

I pedal the dirt path back to the pavement at the streetlight--my empty trailer bouncing over the ruts--thinking about when I saw the ad for the caimans posted outside the bathrooms at the Chevron gas station, duct-taped to the wall. It read:

EXOTIC SOUTH AMERICAN CROCODILES

Growing Too Fast. Over Four Feet. Must Sell. Cheap.

And reading that was like when I change gears on my bike and they grind for a second and it feels like the chain’s going to bind up and break, but then it slips into the right place and suddenly I’m in a good gear and there isn’t even a noise and I’m pedaling along the road like I’m flying.

I cruise down the street to the backside of the park where I can push through the gap in the hedge. But before I go home, I stop at Mr. Tyler’s single-wide, stash my bike and trailer under two huge rhododendrons, and sneak up to his porch.

The warm stink is awful. I hold my breath and look to see if anyone’s around. Check up and down the street. Wait and listen as I crouch at the top of his front steps. The green plastic turf on his porch--shining in the light of the streetlamp--looks like layers of shaved wax.

I haven’t pissed in hours, my bladder full. I whip it out and start pissing on the railings, across the front of the porch, take a step and splash some of it on the rocking chair, and as I’m finishing, turn and let the last few drops dribble down the front steps.

No one sees me, and I hop off the porch and jog back to my bike.

Jeopardy! and AP Lit

That night, before I go to my tent, I check on my grandma. She’s in bed watching Jeopardy!, talking to the TV. I sit next to her as she says, “What is heliocentrism?”

One of the contestants says, “What is heliocentrism?”

Then the host says, “That is correct.”

I say, “Hey, Grandma, how are you feeling?”

My hand’s next to her on the bedspread. She pats my fingers. “I’m doing well,” she says. “Quite well.”

“Really?”

She smiles at me and squeezes my hand. “I think so. As well as can be expected.”

The contestant on the show picks another square and the host reads the answer. Grandma says, “Who is Henry the Eighth?”

The contestant says, “Who is Henry the Eighth?”

I say, “Is this a rerun or do you always just know the answers?”

Grandma smiles at me. “I was a high school teacher for 36 years, sweetie.”

“And that’s how you learned everything?”

“Well, my first school was a small school and I had to teach five different subjects while I was there, so I learned a lot along with the students.” She squeezes my hand again.

I say, “Did you like teaching?”

“Yes,” she says. “Definitely.”

“Then tell me a story.” I’ve always liked her stories, it doesn’t matter what they’re about. When Grandma and I used to go out in the canoe together, she’d tell me stories the whole time.

“Okay,” she says. “Let me see. . . .” She drums her fingers on the back of my hand. I can tell she’s thinking because she doesn’t answer the next Jeopardy! clue.

“Okay,” she says. “This one’s from one of my last years of teaching.” She shifts her shoulders. Resettles on her pillow. “I was teaching AP literature to a class of 35 students. There was this one boy, sort of like you, looked like you, had a serious face all the time like you, but he was always falling asleep in class. He was a bright enough boy, but I couldn’t keep him awake when I lectured. So one day, while he was asleep, I walked right up to him and leaned in close to his face and blew on his nose. When that woke him up, I said, ‘I almost kissed you. One more second, and I would have.’ ”

“You said that?”

“Yes. And you should have seen his face. I was almost 70 years old by then, all wrinkly and shrunken down, and he just about jumped out of his chair when he saw my face so close to his. I told him I couldn’t wait for another chance to kiss him, that I would take that very next chance to plant a big wet one on his lips.”

“Grandma.” I shake my head. “He never fell asleep again, did he?”

“No,” she says. “He almost did so many times, but then he’d sort of startle awake, and I’d see him check to see where I was in the room. Everyone else would see that too. His classmates would watch him, especially if he seemed tired. It became a sort of fun side story in that class, something that thickened the plot.”

“He was probably terrified.”

“He was a really nice kid. I just wanted to pull his leg a little.” Grandma shifts again on her pillow, makes a small noise in her throat like she’s trying to swallow something sharp.

“Are you okay?” I say. “Are you hurting a lot?”

“A little. But I’m okay.” She closes her eyes.

“Do you need a pill?”

“No,” she says. “I don’t like the pills.”

“Are you sure? You might need one.”

“No thanks. I just need some sleep.”

I kiss her forehead and stand up. “I’ll let you rest.”

When I’m at the door, she says, “Travis, you know I love you?”

I look back and she has her eyes closed, her head tilted to the side.

My eyes get itchy and I open my mouth, but I can feel how creaky my voice is going to sound, so I don’t say anything.

Somehow Grandma knows I’m still in the doorway. “You sleep well tonight,” she says. “36 nights in a row?”

“Yeah. Good memory.”

She smiles, her eyes still closed. “Goodnight, sweetie.”

“Goodnight, Grandma.”

Coming down the hall, I hear her say, “What is photosynthesis?” just before the TV contestant says, “What is photosynthesis?”

When I enter the living room, I see a light, a spark, out on the back porch. I stop and watch. There’s the spark again, then a flame above a pipe, and I see my grandpa’s face lit by that small light. Grandpa inhales, holds his smoke, and exhales. He’s standing sideways, not looking in the house but down at the pipe in his hands. He sparks the lighter and puffs again. Turns and looks out at the lake. I stare at his dark outline.

There’s a paperweight on the table, smooth and round and heavy, with zion national park chiseled into it. I think about throwing it through the plate glass, watching the glass shards explode onto my grandpa. I pick it up, hold it in my hand. Then I set it down. Turn around. Go back to the bathroom and brush my teeth, wait, lean against the wall, wait until I hear my grandpa come into the house and walk past me, down the hall to his bedroom.

Then I leave the bathroom, go through the living room and out onto the back porch, through the thick marijuana smoke hanging under the eaves.

Down at my tent, Creature’s left a page of his writing on my sleeping bag.

The Pervert’s Guide to Russian Princesses

Princess #3 (Second Draft)

Princess Nina Georgievna, your face long enough to travel by car, your memories of your father like the color indigo at the break of midnight, executed Romanovs in 1919.

You tell me to come forward. You do not look at me as I walk around you. You hold up one finger, spin it in the air, and I keep walking.

Royal. You make your hand flat and I stop.

This is what I must do:

Lean in. A bottle of pure Mexican vanilla in your purse, I smell the scent behind your ears.

Stand behind you and peel the dress off of your shoulders. Run a finger down the ticked line of your spine.

Use my thumbs to rub the knots in your trapezius muscles.

Make up stories about your father being alive and well, hiding in Northern Europe, in Sweden, in an apartment in Stockholm.

Tilt your head back and suck softly on your neck as your breathing gets heavy.

Let you take my hand and guide it down the loosened front of your undergarments where there never was a bra.

Turn you around. Get down on my knees as you hike up your hem, the lace sliding to the tops of your thighs.

Swimming in Circles

Sunday evening. I walk along the shoreline north, toward where I released the caimans, making my way slowly through the bigger blackberry growths, ducking under vines, and stepping through the tall grass where it’s grown over the trail.

I spook a gopher snake, five feet long and bulging with a rat. The snake slides out in front of me on the narrow trail, the rodent dragging along in the middle of its body, and I smile and walk behind it until it cuts a hard left into the heaviest of the blackberry thickets and I can’t see it anymore.

At the small beach where I released the caimans, I find only two rubber bands and a piece of duct tape. No duffel bags. I look around, but they’re nowhere. Someone must have taken them. I pick up the rubber bands and the duct tape and put them in my pocket.

Searching the shore, I expect small animals ripped apart and hundreds of crocodile footprints. But there are no tracks, no clues. I crouch down where the mud meets the round rock, but I don’t see anything. I check in the bushes, the reeds at the lake’s edge, and under the willows. I crawl beneath the blackberry overhang and start to worry. What if the caimans died right off? What if that first night was too cold even though it’s summer?

I look up and see a girl walk out onto one of the docks in front of me, a few docks down. I’ve never seen this girl before, a teenage girl, thin, athletic-looking. Tall. Straight dark hair. I watch her walk to the end of the dock, bend down, and put one of her hands in the water. She’s on her knees.