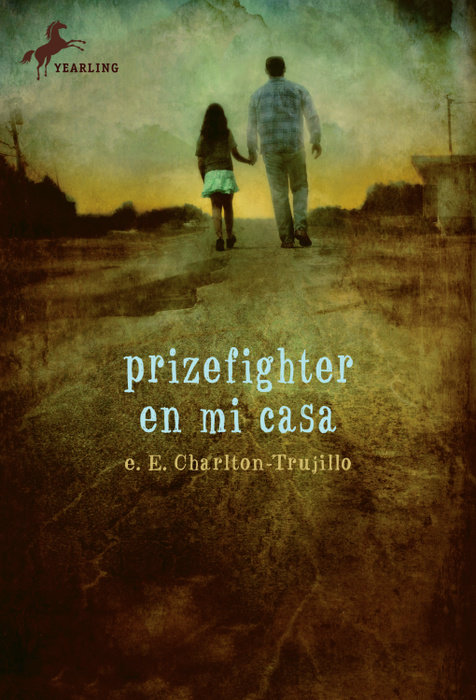

Prizefighter en Mi Casa

Twelve-year-old Chula Sanchez isn’t thin, isn’t beautiful, and because she’s Mexican, isn’t popular in her south Texas town. And now that a car accident has left her father paralyzed and her plagued with seizures, she is poor. But Chula’s father is determined to pull his family out of debt. He sends for El Jefe—the most revered prizefighter in Mexico. Chula’s father hopes that with steel-pipe arms and fists like pit bulls, El Jefe will win the local illegal boxing matches and bring home much-needed money. But El Jefe—a man who many see as a monster—only brings confusion to a home that is already filled with problems. And now Chula must decide for herself whether good and bad can reside in one person and whether you can have strength in your heart when your fists have none.

An Excerpt fromPrizefighter en Mi Casa

1

A gutted pumpkin glowed from across the street. The streetlight closest to the house got shot out almost one whole year ago so I could barely see nothing. Nothing but that glowing orange head without a body.

I sat on the porch swing hoping to stay outta Mama’s way. She was in one of those moods again where she cursed the saints she’d be praying to later. Being Mexican and Catholic requires a lotta prayers. Even if they never seem to be answered you’re still supposed to make ’em. But I’d quit that after all the glass.

The latch on the gate banged shut only I couldn’t see nothing but a shape, a moving shadow with footsteps. Footsteps that made the porch stairs cry and moan. It walked right past me sitting on the swing and knocked on the screen door. I sat there all quiet but the swing squeaked. The Shape turned toward me. I didn’t know what it was but it was big. Really, really, really all kinds of big.

The porch light flicked on and the Shape winced and fell back a step. Like when you go out into the sun after being somewhere really dark.

Mama opened the screen door saying “Hector” over her shoulder to my father.

Mama and I kinda stared. I couldn’t believe that was the man my father believed was our family’s gold.

The wheels of Pape’s chair grinded against our wood floor. “Come in, come in,” Pape said from inside the doorway.

Mama held the door open and took the Dark One’s suitcase as he slipped inside.

“Chula,” Mama said. “Get off the swing and get in here.”

I started shaking my head.

“Andale,” she said. “I’m not telling you again.”

I pushed off the swing and went to the door.

“What did you say to him?” she asked me.

“I didn’t say him nothing.”

“Listen. Like it or not, that is all we have. God help us,” Mama said. “So don’t do anything to upset him. ¿Bueno?”

I stood there not saying nothing.

“What? I don’t have all night,” said Mama. “Get in here.”

I ducked under her arm and followed her into the kitchen.

“Get the iced tea,” said Mama.

“Hello, Abuela,” I said to my grandmother.

Abuela leaned back in a chair at the kitchen table. Smiling, with her hands crossed in her lap. Her eyes half-open, half-closed like cats when they go to sleeping. Only she wasn’t sleeping. Not really.

“The tray, Chula,” said Mama. “Come on.”

Mama poured a bag of Tostitos into our sort of fancy lime-colored plastic bowl. She stepped around me and grabbed the homemade picante sauce out of the fridge.

“It’s staying with Tío Tony, right?” I asked her.

“He. His name is El Jefe and that is what you and your brother are to call him,” said Mama.

“Or he might do worse than kill us,” my dumb older brother Richie said, strutting into the kitchen all tough-like. “He might box our ears off so we can’t hear nothing.”

“Shut up,” I said.

Richie grinned, chomping into a chip.

“No sir,” Mama said, pulling the bowl away. “This is for El Jefe.”

“Pues, you see the size of that guy?” Richie asked Mama. “He’s like the Mexican Hulk.”

Richie stuck his hand back in the bowl and she slapped it.

“¿Qué pasó?” asked Richie.

“No jokes. No nothing,” said Mama. “This man has come a long way to help this family.” Then she looked at me. “And he’s staying here.”

I looked at her like she’d just lost her mind.

“Cool,” Richie said.

Mama walked over to Abuela and squeezed her hands. Abuela didn’t do nothing. Not even blink. If her chest wasn’t moving up and down, I would’ve thought she done died. Done died right there in South Texas dreaming of Mexico.

Mama turned on the radio. We only had one in the house and it played only for Abuela. Sometimes she’d get to looking too distant from us and closer to God, and Pape didn’t like seeing his mama like that. The music seemed to return part of her to us, even if it was only for a while. But one thing I learned about a while in my family, it was never very long but it was longer than never and you always have to aim for that. Never means nada and nada means nothing and we want more than that, Mama always says. You must always want more than your history.

Mama weighted me down with the tray of cups and iced tea. Richie scooped up the bowl and salsa and we followed behind her.

Pape was smiling and happier than I’d seen him in like forever when we came into the living room. Mama stacked the magazines and free TV guide from the neighbor’s Sunday newspaper under the coffee table so she’d have a place to put tea and chips.

“I’m sorry,” said Mama to the Dark One. “We weren’t expecting you until tomorrow morning.”

He nodded but didn’t take his eyes off the floor. Really his eye ’cause he only had one. The other was under a dusty patch with clawlike scars that went up all high on his head and spread outta the bottom like crooked fingers. I wondered if they hurt as much as the one on the side of my head.

Mama took the tray and chips from me and Richie and I stood there still looking at the creature out of the corner of our eyes. No way could it be true that Pape useta stick up for El Jefe when he was little. How could that Cyclops ever be that small?