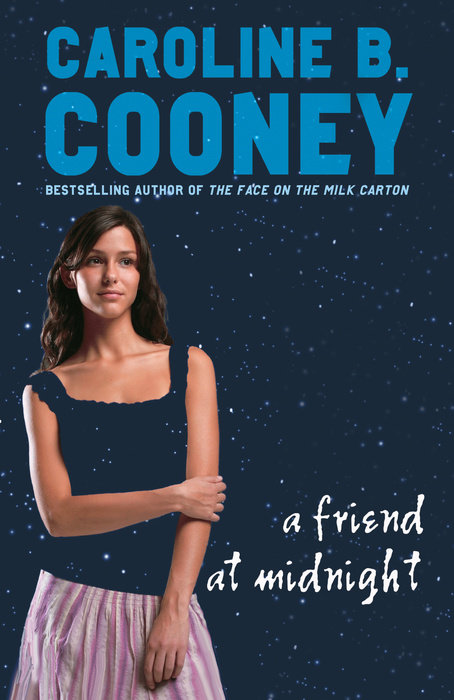

A Friend at Midnight

Lily has settled into life in Connecticut after her parent's divorce but it's been harder on her eight-year-old brother Michael. After their mother remarries, her brother chooses to go live with his father in Washington, D.C., until the day he calls home from the Baltimore-Washington Airport where his father has abandoned him.

Lily is home babysitting her baby stepbrother when she answers the phone. She has no idea the extent to which her faith in God will be tested. There is no choice for Lily. She will rescue Michael, but will she be able to rescue herself from the bitterness and anger she feels?

An Excerpt fromA Friend at Midnight

* chapter 1

For miles, nobody spoke.

Then the driver stopped right in the road and said, "Get out of the car."

Michael's fingers struggled with the latch of his seat belt. The driver reached over with such irritation Michael expected a slap, but the driver just released Michael's seat belt. It was gray and shiny and slid away like a snake.

The car door was heavy. Michael opened it with difficulty and climbed out onto the pavement. The passenger drop-off made a long dark curve under the overhang of the immense airport terminal. Glass doors stretched as far as Michael could see. Men and women pulled suitcases on wheels and struggled with swollen duffel bags. They hefted briefcases and slung the padded straps of laptop carriers over their shoulders. The glass doors opened automatically for them and the airport swallowed them.

"Shut the door, Michael," said the driver.

Michael stared into the car. He could not think very clearly. The person behind the wheel seemed to melt and re-form. "You're not coming?" Michael whispered.

The driver answered, and Michael heard the answer. But he knew right away that he must not think about it. The shape and contour of those syllables were a map of some terrible unknown country. A place he didn't want to go.

"Shut the door," repeated the driver.

But Michael could neither move nor speak.

Again the driver leaned forcefully over the passenger seat where Michael had sat. Michael backed up, the heels of his sneakers hitting the curb. The driver yanked the door shut and the car began leaving before the driver had fully straightened up behind the wheel.

Michael stared at the back of the car, at its trunk and license plate, and immediately his view was blocked by a huge tour bus with a red and gold logo. Passengers poured out of the bus, encircling Michael, talking loudly in a language he did not know.

The bus driver opened low folding doors covering the cargo hatch and flung luggage onto the sidewalk. Bus passengers swarmed around the suitcases. Michael watched as if it were television. When all the luggage had been distributed, the driver folded the doors back, leaped into his bus and drove off.

Michael could see down the road again, but the car that had dropped him off was long gone. airport exit, said the sign above the road.

Three cars drove up next to his feet. Families got out. People kissed good-bye. They vanished into the maw of the airport. Another bus arrived, all its passengers either old ladies carrying big purses or old men carrying canes and newspapers.

Michael felt eyes on him. Not bus people eyes, because the bus people were too busy making little cries of pleasure as they spotted their suitcases.

He didn't have to look to know they were police eyes focused on him. He was not going to tell the police. Not now, not ever.

Michael eased into a knot of bus people, resting his hand on the edge of an immense suitcase towed by a fat chatty lady. Another even fatter lady towed an even larger suitcase. Wherever they were going, they could hardly wait to get there. The ladies hauled their suitcases into the terminal. Michael went with them. The women never noticed him, but surged forward into a ladies' room. Michael stood in the midst of a vast open area. Hundreds of passengers hurried by, separating on either side of him as if he were a rock in a river. They gave him no more attention than they would have given to such a rock.

Michael threaded his way down the concourse until he came to flight monitors high on the wall. Michael was not a good reader. Charts, like the departure and arrival lists on these screens, were difficult for him. Craning his neck and squinting, he struggled to interpret the information. There were several flights to LaGuardia. He counted six in the next two hours. He hung on to this information, as if it might be useful.

Michael was wearing new jeans. It was too hot for jeans, but he had been told to put them on. The crisp pant legs were rough against his skin. His T-shirt, though, was old and soft. It had been his sister Lily's, and he had filched it from her to use as packing around a fragile possession. He had been wearing it lately, even though it came to his knees.

He felt those eyes again. He walked into the men's room to get away from the stare. It was packed. So many men. Fathers, probably, or grandfathers or stepfathers or godfathers. He closed himself in a stall, but the toilet was flushing by itself, over and over, as if it intended to drown him, and he fled from the wet sick smell of the place.

Back in the open space, Michael distracted himself by looking everywhere, even up. The ceilings were very high, with exposed girders in endless triangles that looked like art. He had been in this airport once before and had imagined swinging from those girders, leaping from one to the next, sure of his footing. Michael was not sure of anything right now, not even the bottoms of his feet.

He sat on a black bench that had curled edges, like a licorice stick. Ticket counters stretched in both directions: American, Southwest, Continental, Frontier, Delta. People stood in long slow lines that zigzagged back and forth, separated by blue sashes strung between chrome stands.

Maybe I just didn't understand, he thought. Maybe the car just went to park. Maybe if I go back outside . . .

He felt better. He went back outside.

Taxis and hotel limousines and vans from distant parking lots were driving up. Wheeled suitcases bumped over the tiled sidewalk as loudly as guns shooting. Clumps of people stumbled against him and moved on. New buses took the place of the last set, and their exhausts were black and clotted in his lungs.

The terrible words the driver had flung at Michael had been lying on that sidewalk, waiting for him to come back, and now the words jumped up and began yelling at him.