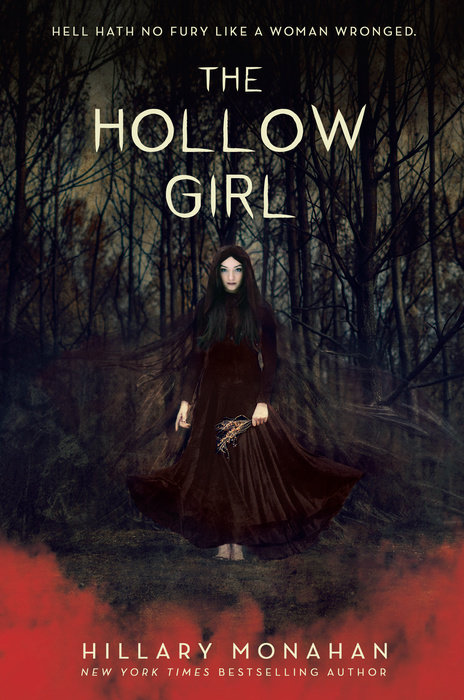

The Hollow Girl

For fans of Asylum, Anna Dressed in Blood, and The Haunting of Sunshine Girl comes a new feminist horror novel from the New York Times bestselling author of Mary: The Summoning.

Five boys attacked her.

Now they must repay her with their blood and flesh.

Bethan is the apprentice to a green healer named Drina in a clan of Welsh Romanies. Her life is happy and ordered and modest, as required by Roma custom, except for one thing: Silas, the son of the chieftain, has been secretly harassing her.

One night, Silas and his friends brutally assault Bethan and a half-Roma friend, Martyn. As empty and hopeless as she feels from the attack, she asks Drina to bring Martyn back from death’s door. “There is always a price for this kind of magic,” Drina warns. The way to save him is gruesome. Bethan must collect grisly pieces to fuel the spell: an ear, some hair, an eye, a nose, and fingers.

She gives the boys who assaulted her a chance to come forward and apologize. And when they don’t, she knows exactly where to collect her ingredients to save Martyn.

“Hits the horrifying notes: dread and darkness and grisly ends, yet somehow still feels full of heart…I couldn’t tear my eyes away.” —Kendare Blake, NYT bestselling author of THREE DARK CROWNS

“A richly woven tapestry of magic, betrayal, and revenge told by a strong, spirited heroine who won my heart, broke it to pieces, and then healed it anew. Brava!” —Dawn Kurtagich, award-winning author of The Dead House

"A cathartic revenge fantasy...Quentin Tarantino-style." —Kirkus Reviews

"An eerie, unsettling novel that will linger long with readers." —Booklist

"Dark, intense, and full of magic." —VOYA

An Excerpt fromThe Hollow Girl

Chapter One

My chin rested in my palm. My eyelids were heavy. Gran’s arm darted out, her liver-spotted hand whacking the inside of my elbow to knock it off the table. It pulled me out of my stupor, but almost cost me my teeth.

“I am not saying this twice.” She reached for a cluster of herbs hanging from a hook in the ceiling and snapped off two sprigs of green with dusky-purple flowers. “Dwayberry.”

“Nightshade,” I said, fairly certain I had it right.

She flipped over the stems, showing the shiny, dark berries on the underside. They were beautiful, fat and juicy, like they belonged in a pie. Gran jiggled them in front of my nose and they made a rustle, rustle, rustle. “Small doses numb pain, larger cause hallucinations. More than that is the pretty poison--it is sweet to the taste, so they smile before they die. Seven to kill a child, twenty to kill a man. Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“ ‘Yes’ what?”

“Yes, Gran. I understand.”

Her left eye swept over my face, the pupil milky white and covered by what she called her ghost shroud. It was not a source of power, she told me once, even if people assumed otherwise.

“My gift of sight has nothing to do with my blindness, nor does it have anything to do with our Romani blood,” she’d said. “I was born with a caul upon my face. Lifting it lifted the veil between worlds, sometimes allowing me glimpses of what will be. The eye is a theater prop--nothing more.”

Her sight must not have shown her much at that moment, though, as she turned her head to set her brown eye upon me, searching for cheekiness I didn’t wear. I’d learned at a young age never to sass my grandmother. Other children had their hands slapped or their bottoms paddled when they were ill-mannered. I’d once lost the ability to speak for two days. Another time, she’d bound me to a chair for three hours without ever touching me with rope.

“I’ve been studying herbs for five years.” I kept my voice even, neutral, so she wouldn’t accuse me of whining. Gran always punished whining with the worst chores, like gathering stinkgrass by the bucketful. “I’d like to study magic. You said anyone can do it with training.”

She talked about it sometimes, about the hearth witches of Ireland granting powerful blessings and casting terrible curses. The English witches could hear the wind’s whispered secrets and control the weather. The Scottish witches had mastered fire and water, just as our Welsh kinsfolk could influence dreams. The magic Gran claimed--that I would one day claim--was vast and varied, picked up over generations of traveling.

I hung from every story Gran told about it, mostly because she was never forthcoming with details about the spellcraft, always exiling me from the vardo when there was witchwork to do. My education was her rare offered snippet or fireside story hours with the other children.

Both left me with more questions than answers.

Gran snorted and tossed her head, locks of gray hair slithering past her shoulders. It had started off in a tight bun beneath her red scarf, but the hours had disintegrated it to a stringy, sloppy mess. “You barely pay attention to herbcraft.”

“Because I know much of it already. I want to learn something new!” I’d already learned how herbal tonics saved lives under the best conditions, and under the worst, ended them. That was the part that interested me. She’d lost me when she droned on about the responsibilities of herbcraft.

“I will be the one to determine when you are ready.” She pushed herself from the table, her back hunched as she hobbled through the vardo, past the window, and toward the cot in the corner. She reached for a basket of curatives and charm bags, riffling through the sacks to ensure everything was accounted for. The cures were real enough: some for sour stomach, others for a pained head or aching bones. I knew which was which by the colored yarns tied around the pouch tops. The charm bags sold better, but they were novelties--usually the refuse of the plants we’d used for the medicines. Gran would throw an animal bone or a shiny bead inside to make them look more legitimate, but there was no magic there. It was a pretend solution for a bargain price.

She slid the basket my way. “Do not come back from town until you have coin in your pocket. And wear your scarf over your face. We do not want trouble.” I flinched at the reminder, but she ignored me, pulling a silky black scarf off her mirror, her fingers sliding along the silver-threaded edges. “Wear this one. It is pretty.”

I took it with a muttered “thank you,” winding the scarf over my head and tucking it around my nose and mouth, over my birthmark. I’d been born with half my body painted wine, the other half so pale one wondered if I’d ever seen the sun. Gran called me her eclipse. I was dark on the left, light on the right, and some people--outsiders, the gadjos--recoiled, claiming I’d been touched by evil while in my mother’s womb. When I’d gone into Anwen’s Crossing for the first time the week before, a woman screeched at me, insisting I renounce the devil. I’d assured her that I and my people were Christians like her, but it hadn’t mattered. Only the pity of a local priest had kept her and her friends from jabbing me with pitchforks and flaming torches.

I’d never been so afraid in my life. I’d run all the way back to the caravan, a mile from town, breathless and trembling and half expecting the angry faces to haunt my shadow. Gran had listened to my babbled excuses, nodded, and squeezed my shoulder in sympathy, but she wasn’t happy. We depended on the income from market sales, and now we’d need to make two weeks’ worth of sales instead of one to recover our losses.

Gran peered at me a moment before tugging my braid from under the fabric, the dark coil interwoven with pretty ribbons.

“Such beautiful hair.” She smiled faintly, letting me know she cared for me even if she was as demonstrative as stone. “Keep your wits about you. Stay sharp.”

“I will. I’ll be home before dark.”

“Of course you will. With coin in hand this time, no doubt.”

“Yes, Gran.”

“Good. Now shut your mouth and go.”

As soon as I was out the door, I wished Gran were going in my stead. Until last season, I’d been the one assembling the herb bags while she hawked our goods at open market, but her legs had worsened over the winter. She needed a cane more often than not, and walking to town would cripple her. As I was a healthy young woman in her prime, it only made sense to have me take over sales duty.

The real money was in spellcraft, of course, but Gran was very particular about who she’d work with. The gifts most outsiders expected of her were as shallow as their opinions of our people, so that was all she was willing to provide them--shallow magic. Fortune-telling and false charms, empty predictions about lackluster love lives. Gran used their biases against them--a blind eye that sometimes made her stumble on uneven ground or bump into furniture became a gateway to another world, granting her visions of what had been and what would be.

But those who respected her and her craft--usually Roma and friends of Roma--could buy true magic in all its wonders and horrors. Saving a life, changing a fate, blessings, and scrying to see the future.

As we’d only been parked in the area a week, no one had come looking for spellwork yet. Until they did, I would persevere and cover my face in hopes that it would keep me safe from superstitious ignorance. Maybe the priest would be there to help if things got out of hand again. And if not, I had strong legs. I could run like a colt if the need arose.

I rounded the last of our vardos and tents and passed our grazing horses to approach the road, my eyes skipping to the great fire at the center of our caravan town. It was the designated meeting place for my people to talk, cook, and conduct business throughout the day. Everyone gathered there after hours, when the coffee flowed like water and fiddles and harps wailed their songs. I smiled, hoping I might get back in time to dance before bed, but then I caught sight of Silas and his band of horrible friends standing near the cookpots, and my smile went to the wind. I put my head down and walked faster, my fingers tugging the scarf higher on my face. Maybe it was enough of a disguise to keep me beneath his notice. Maybe he’d dismiss me as some other girl.

Most of my clansmen treated me with respect. I was the adopted daughter of Drina--Gran--our wisewoman, who’d left her own caravan to stay with us after the last drabarni died birthing me. All I knew about my birth mother was that she’d been called Eira and had been as lovely as a rose bloom, with silky hair and fine teeth. My gadjo father abandoned me upon her death, too distraught to handle the loss of his beloved, and too afraid of his “strange-looking” daughter to raise her, and so I was given into Drina’s care.

Silas Roberts never minded the birthmark that had scared off my own father. He even went so far as to give me special attention, propositioning me whenever Gran wasn’t nearby. It was the ultimate disrespect. He knew that our clan girls went to their wedding beds pure lest they be ostracized, yet he shrugged off propriety and chased me anyway. Perhaps he thought I would be grateful for his advances because I looked different, and other men might not want me. Neither of us had a marriage set up, so perhaps he thought we’d make a suitable pair. It was rare for young adults to not have an arrangement in place, but Silas’s intended had died when he was eleven, and Gran would not give me over to a betrothal knowing I was to be her heir.

That alone should have stopped his pursuit--my relationship to Gran. Gran often said the chieftain was the mind of our people but the drabarni was the heart. She was trusted implicitly with our welfare and, as our healer, was the only one among us who wouldn’t be sullied by touching people’s most personal, impure fluids. Our kin honored her and her wisdoms and turned to her in their darkest hours.

Yet Silas was ambivalent to her station. He lived as if free of consequence, which I supposed wasn’t completely untrue. The chieftain had a soft spot for his youngest child and rarely punished him. Once, after Silas had been caught closing in on another girl in the caravan, the chieftain called him “an unbridled stallion ready for a filly,” dismissing his wickedness as “boyish exuberance.”

I had no interest in such boys.

Seeing him standing there with his hands buried in his pockets and a lopsided sneer on his face, my gripes about going to town disappeared, and I lifted my skirt a few inches to walk faster. As I ducked behind one of the vardos, there was a shrill whistle, followed by a chorus of masculine laughter. When Silas laughed, his friends laughed, like a pack of jackals. They did everything together and had since they were babies, all born within two years of each other, the oldest then eighteen, the youngest sixteen. They were so inseparable, I’d mused before that the five of them shared a single twisted mind.

“Bethan, why so fast? Slow down and say hello. It’s a beautiful day.”

I disagreed; the morning air carried a chill that shredded through my clothes, but saying so would engage him in conversation, and that was akin to letting the devil into one’s home. Instead, I made for the road at almost a trot, the basket swinging by my side. I had a ways to go. Our camp bordered fields of barley and wheat, and the local farmers had built crude wooden fences to mark property lines. The only way to get around them was to walk until there was a break.

I contemplated vaulting the pasture fence by my side, but our customs dictated that I comport myself as a lady at all times, never showing anything above the ankle to a man other than my husband, and leaping a fence would lift my skirt past my knees. If Silas followed me, he might interpret the gesture as an invitation, and he was handsy enough already.

I heard footsteps approaching as someone--a few someones--trailed me: two behind, two alongside, and one at the front. I spotted a break in the fence ten yards ahead, and I darted for it, but Silas leaped out from behind one of the goods wagons to block my path. I stumbled back, my heart pounding, but a pair of hands pressed against my shoulders to shove me forward again. I spun my head to see who was there. Mander and Cam stood shoulder to shoulder behind me, a wall preventing my retreat.

Mander was tall and thin with dark hair worn to his shoulders, his cheek bulging with the tobacco he always chewed. Cam was bigger, broader, and fairer of skin, with dark hair shorn short and gray eyes he’d inherited from his diddicoy mother.

If I peeked around the vardo to my left, I was sure I’d see skinny, befreckled Tomašis and stout, dark Brishen, both jackals awaiting Silas’s instructions. Growing up, they hadn’t been bad boys, but as Silas poisoned the well, they drank from his waters until they, too, were sick.

“I was talking to you.” Silas closed the gap between us. He dipped his head to look at me from beneath the dark arches of his brows. To most girls he was handsome, with hair so black it shined blue in the sun; a long, hooked nose; wide lips; and high-sculpted cheekbones, but my distaste for him made me think of a crow, his hair too glossy, his eyes too dark, his chin too pointed. Crows were eaters of death. I could not and would not like anything of their ilk.

I hoisted the basket in his direction, counting on the woven reeds to keep a respectful distance between our bodies. “I have to get to town. The market day is starting soon, and Gran wants . . .”

“Soon. Relax. Be sweet for me.”

When Silas stepped forward, I took another step back, and the other boys tittered with sinister joy. Mander pushed me straight at Silas and Silas batted the basket aside, his arm looping around my waist to pull me close, until I was pressed against him. Some of my poultices spilled onto the grass below, and he stepped on them, oblivious to their importance, his hand stroking my back in far too intimate a gesture.