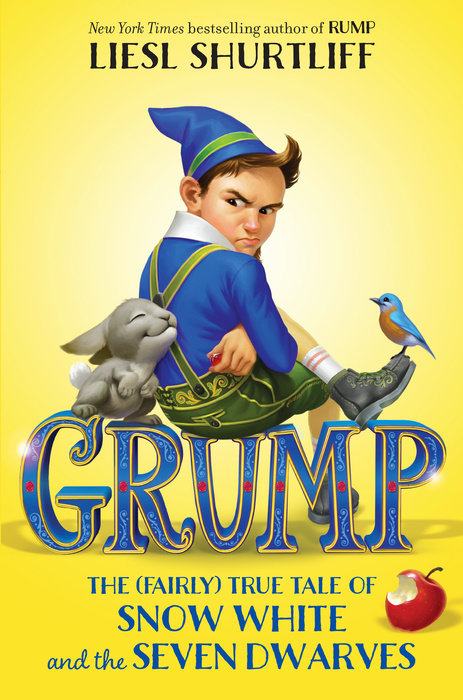

Grump: The (Fairly) True Tale of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves

From the New York Times bestselling author of Rump comes the true story behind another unlikely hero: a grumpy dwarf who gets tangled up in Snow White's feud with the wicked queen.

Ever since he was a dwarfling, Borlen (nicknamed "Grump") has dreamed of visiting The Surface, so when opportunity knocks, he leaves his cavern home behind.

At first, life aboveground is a dream come true. Queen Elfrieda Veronika Ingrid Lenore (E.V.I.L.) is the best friend Grump always wanted, feeding him all the rubies he can eat and allowing him to rule at her side in exchange for magic and information. But as time goes on, Grump starts to suspect that Queen E.V.I.L. may not be as nice as she seems. . . .

When the queen commands him to carry out a horrible task against her stepdaughter, Snow White, Grump is in over his head. He's bound by magic to help the queen, but also to protect Snow White. As if that wasn't stressful enough, the queen keeps bugging him for updates through her magic mirror! He'll have to dig deep to find a way out of this pickle, and that's enough to make any dwarf Grumpy indeed.

An Excerpt fromGrump: The (Fairly) True Tale of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves

I was born just feet from the surface of the earth, completely unheard of for a dwarf, but it couldn’t be helped. Most dwarves are born deep underground, at least a mile below The Surface, preferably in a cavern filled with crystals and gems: diamonds for strength, emeralds for wisdom, and sapphires for truth.

Mothers and fathers try to feed their dwarflings as many healthy powerful gems as they can within a few hours of birth, to give them the best chance in life. But I was fed none.

My parents had been traveling downward the day I was born. Mother could feel me turning hard inside her belly, a sign that the time was drawing near. She wanted the very best for me. She wanted to be as deep in the earth as possible, in the birthing caverns, with their rich deposits of nutritious crystals and gems. But as my parents traveled downward, before they had even descended below the main cavern, there was a sudden collapse in one of the tunnels. The rocks nearly crushed my mother, and me with her. My father was able to get us out of the way just in time.

Unfortunately, the collapse had blocked the tunnel, so we had to go up to find another way down. The strain of the climb was too much for my poor mother.

“Rubald!” she cried, clutching her belly. “It’s time!”

And there was no time to waste. A dwarfling can stay inside its mother’s belly for a solid decade or more, but when we’re ready to come out, we come fast.

And so I was born in a cavern mere feet below the earth’s surface, where roots dangled from the ceiling, water trickled down the walls, and the only available food was a salty gruel called strolg, made out of common rocks and minerals. Mother was devastated.

“My poor little dwarfling!” she cooed as she spooned the strolg into my mouth, then fed me a few pebbles to satisfy my need to bite and crunch. “What kind of life will he have, Rubald?”

“A fine life, Rumelda,” said my father, ever the optimist. “A happy life.”

“And what will we call him?”

My parents both looked at their surroundings. Dwarves are usually named with some regard to the gems and crystals within the cavern in which they are born, but there were no diamonds or sapphires in that cavern. Not even quartz or marble. Just plain rocks and roots.

Father brushed his hands over the rough walls, studying the layers of dirt and minerals. “Borlen,” he said with wonder.

Borlen was a mineral found only near The Surface. It was not so common in our colony but useful when it could be found. It was too bitter to eat, but potters liked it because it made their clay more malleable without weakening it. Borlen could also serve as a warning. A mining crew knew by the sight of it that they were digging dangerously close to The Surface. Most dwarves would rather not find any.

“We’ll call him Borlen,” said Father.

“You don’t think that name will make him seem a bit . . . odd?” Mother asked.

“No, it’s special,” said Father. “He’ll be one of a kind, our dwarfling. We’ll get him deep into the earth as soon as possible and feed him all the best crystals and gems. But wait!” My father pulled something from his pocket and held it out to my mother. “I almost forgot. I’ve been saving this from the moment I knew we had a dwarfling on the way.”

Mother gasped. “A ruby!”

Rubies were rare and particularly powerful gems. They could ward off evil, enhance powers, and even lengthen lives. Emegert of Tunnel 588 was said to have found a large deposit of rubies, and he lived for ten thousand years. Two thousand years was considered a good long life for a dwarf.

Mother took the ruby from my father and dropped it onto my tongue. I crunched on the gem, gave a little belch, and fell asleep.

The very next day, my parents tried to move me to deeper caverns, but as soon as they started to carry me downward, I began to cry. The deeper we went, the louder I wailed, until my eyes leaked tears of dust, a sign of deep distress and discomfort from any dwarf.

“Oh dear,” said Mother. “Rubald, I think our dwarfling is afraid of depths!”

“Nonsense,” said Father. “He only needs to adjust.”

But I did not adjust. I cried for hours on end. My parents tried everything to console me. They fed me amber, amethyst, and blue-laced agate. They bathed me in crushed rose quartz and hung peridot above my cradle, all to no avail. And so, distraught from my endless wails, and desperate to try anything, my parents took me back to the cavern near The Surface where I was born.

I stopped crying.

“Oh dear,” said Mother.

“How odd,” said Father.

And after that, my parents were obliged to make my unfortunate birthing cavern our home, hoping my fear of depths would subside eventually. But it didn’t. It only got worse.

For years, my parents worked to get me used to depths. Father tried to lead me a little deeper each day, luring me with my favorite gems and the different sights and wonders of the colony--the lava rivers, the blue springs, the dragon hatchery, the potters and glassblowers and goldsmiths. But no matter how interesting the surroundings, no matter how many sapphires and rubies he offered, my depth symptoms would always overpower me. I’d start to get dizzy, then I’d feel like I was shrinking and shriveling, and we’d have to go back home.

It was shameful enough that I was afraid of depths, but that wasn’t the worst of it. As much as I hated going downward, I was equally drawn to going upward. My first word was “up,” much to my parents’ chagrin, and as soon as I understood that there was an actual world above us, I wanted to know everything about it. I pestered my parents with questions. What did The Surface look like? How was it different from our caves? Did any dwarves live up there? Why didn’t we live up there? Could we go there?

My parents knew next to nothing about The Surface. Neither of them had seen it, nor did they have any desire to. Mother usually sidestepped my questions or changed the subject, but Father indulged my curiosity. He took me to the colony’s records room--a vast cavern filled with many millennia of our history and collective knowledge engraved on stone tablets and slates. Normally, I wouldn’t have tolerated the depths of the cavern, but my thirst for information overcame my fear. I scoured the records for any facts I could find about The Surface. I learned it was a big, open place with an endless blue ceiling called the sky, and a big golden ball suspended in the sky called the sun. There were things that grew on The Surface that didn’t grow underground. Things called trees and flowers and bushes. There were strange beasts that roamed The Surface--horses, bears, and wolves. But the most fascinating of all were the humans.