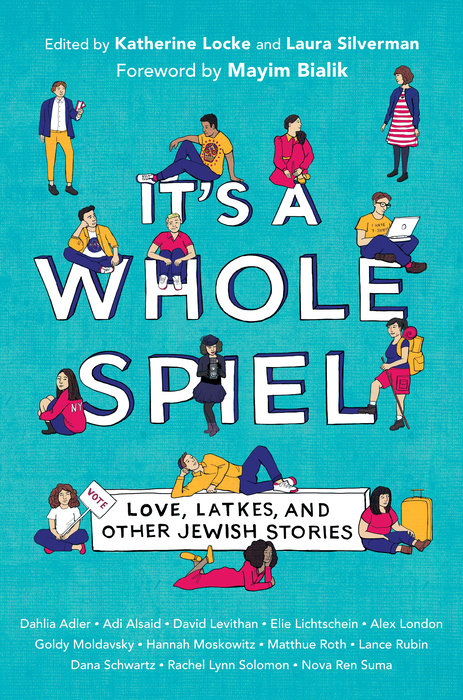

It's a Whole Spiel

Includes a special introduction by Mayim Bialik, star of The Big Bang Theory and author of the #1 bestseller Girling Up!

Get ready to fall in love, experience heartbreak, and discover the true meaning of identity in this poignant collection of short stories about Jewish teens, including entries by David Levithan, Nova Ren Suma, and more!

A Jewish boy falls in love with a fellow counselor at summer camp. A group of Jewish friends take the trip of a lifetime. A girl meets her new boyfriend's family over Shabbat dinner. Two best friends put their friendship to the test over the course of a Friday night. A Jewish girl feels pressure to date the only Jewish boy in her grade. Hilarious pranks and disaster ensue at a crush's Hanukkah party.

From stories of confronting their relationships with Judaism to rom-coms with a side of bagels and lox, It's a Whole Spiel features one story after another that says yes, we are Jewish, but we are also queer, and disabled, and creative, and political, and adventurous, and anything we want to be. You will fall in love with this insightful, funny, and romantic Jewish anthology from a collection of diverse Jewish authors.

An Excerpt fromIt's a Whole Spiel

Indoor Kids

By Alex London

It happened somewhere over Canada, although it had probably been happening since Australia. No one even knew anything had gone wrong until the International Space Station was over the Atlantic, a tiny dot of light heading toward the west coast of Africa, not a single earthly eye on it, and we only found out at camp because Jackson Kimmel had an aunt who worked at NASA.

She was not an astronaut.

She was in human resources, so she didn’t actually do anything with the space program, but she texted her nephew, because space was his “thing,” and her nephew told me, because he knew space was also my “thing,” and that’s how summer camp works: find someone whose thing is your thing and geek out together.

It would’ve been nice if I’d had someone to geek out with who wasn’t a ten-year-old.

“They think it was an impact with space junk,” Jackson said, waving his arms around while he circled me. He was one of those kids in constant, exhausting motion. “Did you know that NASA tracks over half a million pieces of space debris that orbit the earth? It travels at seventeen thousand five hundred miles per hour, so, like, that could cut through a space station. Usually they have all kinds of warnings and ways to maneuver around space junk. They call it the ‘pizza box’ because it’s an imaginary box that’s a mile deep and thirty miles wide around the vehicle, and if anything looks like it’s gonna get too close to the ‘box,’ they take steps to keep the astronauts and the equipment safe, but not all the debris is tracked, so maybe they missed something? My aunt doesn’t know; she just does paperwork for people’s travel to conferences. She got to meet Leland Melvin once. Do you know who he is? He’s spent over five hundred sixty-five hours in space during his career, but you probably know him as the astronaut who took his official NASA portrait with his dogs? You ever see it? The dogs’ names are Jack and Scout. Or Jake? I can’t remember. Do you have a dog? I named my dog Elon, after Elon Musk, but now I think that--”

“Okay, Jackson.” I interrupted his monologue. He had actually made air quotes with his fingers around the words “pizza box.” What ten-year-old makes air quotes? “Take a breath and change for basketball.”

His smile vanished, his face a crash landing, no survivors.

“Do I haaaave to?” he whined. I wanted to tell him, No, of course not! Who sends their ten-year-old space nerd to a sports camp when there is an actual place called Space Camp! Your parents should be punished for this! But sports were required at Camp Winatoo, and Jackson had to go play basketball before he could come back for afternoon science club in Craft Cabin.

It was my unfortunate duty to make him go play basketball, just as it had been some other seventeen-year-old counselor-in-training’s job to force me to go play basketball when I was a ten-year-old space nerd here. That’s the curse of the indoor kids. People are always trying to make us go outside and play. The bastards.

Now I was one of them.

“Yes, you have to,” I told him.

I would have much rather spent the morning talking about the merits of the Falcon 9 rocket in commercial applications, but that wasn’t an option, not if I wanted to keep my job. The silver lining of this job was that I, personally, did not have to go to basketball. I had the entire early afternoon to do what I pleased. I was extremely lucky today, because I didn’t even have to supervise the aftermath of basketball, which was one of the worst jobs you could have. Those kids smelled ripe. Old enough for BO, not quite old enough to have figured out deodorant. And the ones that had figured it out? Axe Body Spray might be the worst thing to have happened in the history of mankind. It’s chemical warfare marketed to tweens.

After Jackson skulked off in his too-big basketball jersey, I pulled out my phone, trying to see if there was any news about the space station. Nothing had hit the mainstream media yet, but @GeekHeadNebula on Twitter had posted about a possible catastrophic hull breach impacting all ISS life-support systems.

That seemed a bit dramatic, in the way of breaking news, and I knew the reality would end up more mundane. Not that the mundane couldn’t be deadly in the void of space. It was usually the mundane that turned deadly up there.

Kind of like my life on Earth.

The Deadly Mundane could’ve been the title of my autobiography. Nothing dramatic ever happened to me. I was a junior counselor at the same summer camp I’d gone to as a kid, where I’d known most of the other junior counselors since forever. Back home, I lived in the suburbs and went to the kind of school where teenagers on the Disney Channel would go: everything was well lit and oversaturated, every adult was caring and concerned and a bit clueless, and every family was more affluent than the national average, but not so affluent that we’d be the bad guys in a dystopian novel.

I’d had my bar mitzvah and come out of the closet the same year, and both went . . . fine. I almost cried when my voice cracked during the haftorah recitation, and I also almost cried when my dad told me he was proud I was “living my truth.” The bar mitzvah involved me getting envelopes with eighteen-dollar checks in them, and coming out involved my mom putting a pride flag on our car. Neither was earth-shattering.