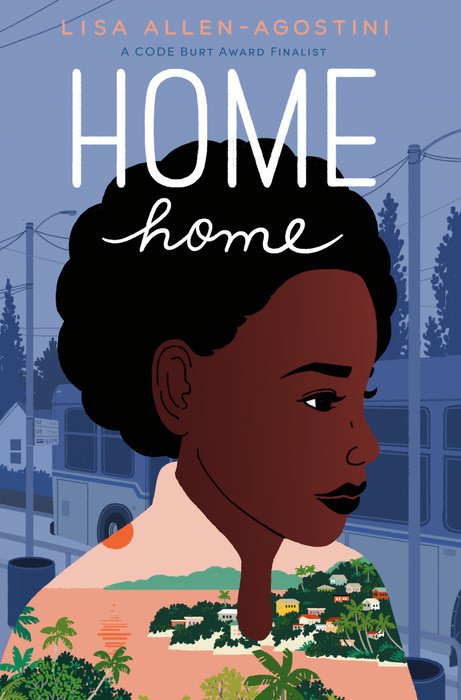

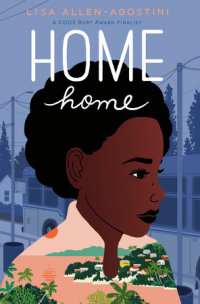

Home Home

Fans of Monday's Not Coming and Girl in Pieces will love this award-winning novel about a girl on the verge of losing herself and her unlikely journey to recovery after she is removed from anything and everyone she knows to be home.

Moving from Trinidad to Canada wasn't her idea. But after being hospitalized for depression, her mother sees it as the only option. Now, living with an estranged aunt she barely remembers and dealing with her "troubles" in a foreign country, she feels more lost than ever.

Everything in Canada is cold and confusing. No one says hello, no one walks anywhere, and bus trips are never-ending and loud. She just wants to be home home, in Trinidad, where her only friend is going to school and Sunday church service like she used to do.

But this new home also brings unexpected surprises: the chance at a family that loves unconditionally, the possibility of new friends, and the promise of a hopeful future. Though she doesn't see it yet, Canada is a place where she can feel at home--if she can only find the courage to be honest with herself.

"A hopeful story about finding one's place."-Kirkus Reviews, Starred review

An Excerpt fromHome Home

Chapter One

That sound; that burbling, bubbling sound. That ringtone was possibly the most annoying sound in the whole world. But it was my lifeline to home.

I hit the big green button. Akilah’s face popped up on my screen. She whispered, “Hey, you. What’s going on?” Akilah was in church clothes, practically shining in a prim little cardigan over a modest dress. I could just see her collar and buttons. She was rushing out of church as we spoke. Her mom would eat that up. Yet another reason for her mother to hate the reviled best friend: I made Akilah leave while the service was going on.

All these thoughts rushed through me between spasms of terror. Those clutching, needle-sharp pains in my stomach had started, and before I dissolved into a puddle of tears and snat I’d had the good sense to send Akilah a Skype message: Not doing so great. Be nice to talk.

What can I say? I have a rare gift for understatement.

Lucky for me, she had her phone on--a no-no, as far as her mom was concerned. “Phones off in church” is a strict rule, as any churchgoer knows. Lucky for me, Akilah realized I was having a hard time and had defied the rule to be there when she knew I needed her. Lucky for me, she was a great friend.

She was my best friend--and she was my only friend.

“God,” I groaned. “Ki-ki, I’m dying.”

“No, girl, you’re not dying,” she responded. She was whispering and walking at the same time; and behind her the sunlight was blinding. She stopped and stood in the dappled shade of a mango tree, its dark green leaves rustling noisily in the breeze. “What’s the matter?”

“Nothing,” I said. “Everything.”

“That’s not an answer,” she scolded me. “What is causing you to feel like this right now?” She was familiar with my panic attacks: I’d get sweaty, my heart would race, I’d feel breathless and terrified and end up sobbing for hours. It wasn’t a good look. What amazed me was that she was always ready to give me a shoulder to cry on. Before I’d gotten to Canada, hers was the only one I had.

“I am walking to the bus stop, trying to get home . . . ,” I started to explain before trailing off.

“And?” She waited for me to answer. It took a while.

I took another step on the long white highway.

It was about seventeen degrees Celsius, warm for Canadians but cold for me; I haven’t gotten used to the weather yet; though we use the same temperature scale as Canada, they use the lower parts much more than we did. For them seventeen degrees is a nice day, and they put on shorts and tank tops and walk around like I would at the beach or in the park, but for me, it’s just another wrap-up-tight day, wear-my-coat day, feel-too-cold day. Home was never this cold, even on the chilliest nights, even up in the high hills of Trinidad’s Northern Range where mist covers the road in the early morning.

Almost as though in sympathy with the windy day in Trinidad, the wind picked up. I felt it blowing through my short black hair, trying to ruffle it and failing. Canadian wind, oh you don’t know anything about hair like mine. You haven’t seen enough of it in this quiet backwoods on the prairie. You think my hair is gonna just submit to you, flip and dance in you, fly and move in you? Not my hair. It’s worked too hard for too long to just give in to you. It’s tough hair, wiry hair, strong hair, hair that won’t be cowed by some damn prairie wind. No sirree, not this hair.

“Sweetie?” Akilah asked sharply.

When I’m having a panic attack I can find it hard to carry on a conversation. My thoughts become confused and all the words become tangled in my mind, a ball of stifled self-expression. So I tried to focus on the road I was walking on.

A long concrete road, it was four lanes wide and full of zooming, beeping, clanking, whooshing cars, buses, and trucks. Trucks especially. They weren’t allowed to drive on the cross streets, only roads that ran the length of this part of Edmonton.

The trucks were big, lumbering, trundling things that passed too close to me as I walked. The pavement and road were the same color, the same texture. Home home, roads were black, the way roads should be. Roads back home were made of asphalt mined from Trinidad’s Pitch Lake. Not here. Edmonton’s bone-white, cold concrete highway scared me in some primal way. This wasn’t a road into anything good; it couldn’t be. And I’d never seen so many trucks. They were like huge devils with horns blaring and fangs in their grilles, evil grins, bad intentions, bearing down on me from behind, leering at me as they powered past, warning me they’d be back for me--not now but at some unspecified, very real date in the future. The wind they raised was bitter and hot, not like the wind that normally blew cold, odorless, and sterile. The wind blown from the sides of the trucks was dusty and tasted like ashes in my mouth.

Houses ran alongside the road. Stretching over the four lanes every now and then was a big blue road sign that told me where I was. I also kept track by counting the street signs at each corner. Twenty-First Street. Twentieth Street. Nineteenth Street. The streets seemed inordinately far apart. I had four more blocks to walk before I turned in to the bus station.

“What’s going on?” Akilah was now insistent. All she’d heard was the jagged sound of my breath as I freaked out, abrupt inhalations and shaky exhalations that would stop me from screaming. I must have looked awful.

“I’m in the middle of nowhere.”

“Why are you walking in the middle of nowhere?”

“I should take a bus from the city to the station, then from the station to home,” I confessed. “But I never remember quickly enough which bus to take to get to the station. I feel like an idiot standing there staring at the transit map. I keep some schedules in my pocket, but . . .”

It sounds stupid, but I was always, always easily flustered when I had choices to make, even simple, everyday ones. Should I have rice or pasta? Lettuce or cabbage? The Fourteen or the Eighteen? My choice could kill me. At least, that was what it felt like. And please don’t get me started on multiple-choice tests. Exams were always hell. I never knew how to decide things.

So instead of trying to figure out which bus to take when my brain was stuck in a goo of confusion, I walked to the little bus station, with its heavy, warm air panting out of buses that crouched in a waiting lane, engines still running. Meanwhile, the drivers used the bathroom or made phone calls to their families, or just chilled with other workers in the small office behind the bulletproof glass of the customer service counter.

The bus schedules in my pocket, clutched too tight too many times, had become grimy and old through the weeks I’d used them. No matter how many times I took the bus, I always forgot which one I needed. I sat and took really deep breaths, I could remember that mornings my bus was the Fourteen, going north into the city; and evenings my bus was the Eighteen, going south into the suburbs. But when I was in the grip of a panic attack there was no way I could remember that, as ridiculous as it might sound. I had to pull out both schedules every time I walked to catch a bus. I had to smooth out the wrinkles, squint down at them and look to see which bus went where. And as soon as I put them back into my pocket I’d forget again. Which bus goes where? What time is it running? Am I in the right place?

Having a panic disorder really sucks.

“You’re not an idiot,” Akilah consoled me. “In fact, you’re one of the smartest people I know. Quick . . . what’s the capital of Moldavia?”

“Moldavia isn’t a country anymore. You’re thinking of Moldova. And the capital is Chişinău.”

“Kitchen-what?” The strange pronunciation slayed her, her laughter momentarily almost distracting me from the blood pounding in my ears, the fear narrowing my vision.

“Chişinău. Google it,” I growled, ashamed that I could instantly recall dotish trivia like that but couldn’t figure out which bus to hop on.

Akilah was on a mission, though. She saw right through my embarrassment and shook her head in exaggerated mock disapproval. “You see? Which fourteen-year-old Trini girl not only knows that Moldova exists, but knows the name of its capital city and how to pronounce it? You’re a genius!”

“Meh,” I said dismissively. “Such a genius I can’t remember how to get home. Every. Single. Day.”

She laughed, but it was a sympathetic chuckle, not a jeer. Trinidadians made jokes about everything. We laughed at life. It was one of the things that made Trinis special, I thought. But my sense of humor wasn’t helping at that moment.

“Could you just talk to me?” I begged. “Tell me what’s going on with school and church and everything. How did you do in end-of-term tests?”

“Oooh . . . I got a B in chemistry,” she began in disgust. “Mr. Look Loy said my project was disappointing. Can you imagine? I never got a B in my life. . . .”

As Akilah started talking to distract me, I noticed the breeze even more. This afternoon wind seemed determined to get to me, to find something it could interfere with. It crept under my jeans and my high collar, trying to penetrate the layers of fabric to reach my skin. I could feel it swirling below my clothes. But I was prepared, too wily for the wind. I had on long underwear.

Summer in Edmonton is not hot, but it’s not cold. Unless, that is, you’re used to living in a furnace. I was. I was from the Caribbean, where an average day might easily be twice as hot as an average Edmonton summer day. What was sixteen degrees when you were really built for thirty-two, when your blood was as warm as the Gulf of Paria when the sun was shining down on the chalky finger of San Fernando Hill? Here, I was always cold, bundling myself up in layers and obscenely more layers, wearing all the clothes in my wardrobe at once.

Like a real Trini, Aunty Jillian laughed at me all the time about that. She and her partner, Aunty Julie, couldn’t understand why I was always kitted out like a bag lady in sweater, shirt, long underwear, jeans, and sneakers after my arrival in Edmonton. On really bad days, like today, I wore my coat, a long velveteen number I bought at a thrift store because I wasn’t going to be in this city much longer and I was sure nobody wanted to spend real money on my “penance” clothes. Already Jillian and Julie had paid for my trip to Canada, had welcomed me into their home, were taking care of me. I felt I owed them too much to accept an expensive, brand-new fall coat when it wasn’t yet fall. I’d have to go back to Trinidad soon anyway.

My thrifted velveteen coat was a rich electric blue, the color of the sky at home when it was just about sunset--not on the side with the lightshow of the sun going down in an orange blaze of glory but the other one, the side where night is creeping up and day is already a memory. The sky could be such an elegant, intense, impenetrable, and unutterably lovely blue. When I saw the coat on the hanger, it seemed it was waiting for me. Everybody laughed at my purchase, especially Jillian, who called it my Princess Di coat. In truth it was too formal, and pretty old-fashioned, but I didn’t care. It fit and I loved the color and the smooth, short nap of the velveteen. The lining was genuine silk, which was heavenly against my hands.

Plus, when you’re wearing a big, thick coat it feels like it’s easy to disappear.

“English and Lit were super easy, like I told you. Oh, and I can’t remember exactly what I wrote for the first Literature essay, the one on Julius Caesar--something about portents, I think--but Miss Ramsubir said she wants to publish it in the School Tie next--”

“What’s the School Tie?” I asked. She’d never mentioned it before.

“The school magazine. She wants me to write for it. . . .”

I was a bit closer to the bus station and Akilah’s voice had calmed me down a little. I could pay attention to small things again, like the flowers in front of people’s houses, or the faint warmth of the sunshine on my face.

“Maths wasn’t terrible. I got two questions wrong in the long paper. I hate graphs.” Akilah groaned theatrically.

I kept walking, making a fist with my free hand and sticking it into my coat’s silk-lined pocket. My short nails pressed pink crescents into my palm, the pain keeping me from screaming out when the scary trucks passed with their horns blaring boooohhhhhppp! Devil trucks.

“Nobody ever stops me or says hello or anything,” I suddenly said to Akilah. “I literally walk around here and nobody says a word. Canadians are so into their own space that they try not to interfere with anybody else’s.”

Akilah, used to my disjointed thoughts during my panic attacks, picked up the ball and ran with it. “Not like the macos we have here in Trinidad,” she teased. “Always minding your business. Aunty Cynthia would have got about three phone calls by now from the neighborhood macos if you were home and going down the highway.”

It was true, sort of. At home--home home, not here--people stopped and talked to perfect strangers. Yes, the macos minded your business like it was their human right to do so. But at least you smiled at them and saw in their faces some emotion. Here, a strange and hostile silence fell when the occasional person came near me. Not that I saw too many people on this terrifying jaunt.

“Nobody even walks here either,” I told her, and moaned. “I’m a freak. Aunty Jillian and her girlfriend would have picked me up from the city if I had asked them to, but that would have meant them driving out of their way.” I bit my lip. “I don’t want to be too much trouble.”