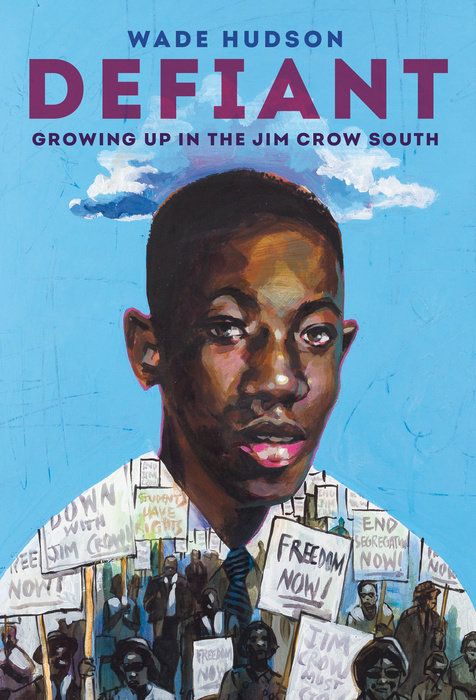

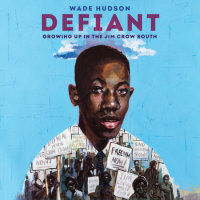

Defiant

In Defiant, Wade Hudson, award-winning coeditor of The Talk and Recognize!, takes a critical look at the strides and struggles of the past in this revelatory and moving memoir about a young Black man growing up in the South during the heart of the civil rights movement.

“With his compelling memoir, Hudson will inspire young readers to emulate his ideals and accomplishments.” —Booklist, starred review

Born in 1946 in Mansfield, Louisiana, Wade Hudson came of age against the backdrop of the civil rights movement. From their home on Mary Street, his close-knit family watched as the country grappled with desegregation; as the Klan targeted the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama; and as systemic racism struck across the nation and in their hometown.

Amidst it all, Wade was growing up—getting into scuffles, playing baseball, immersing himself in his church community, and starting to write. Most important, Wade learned how to find his voice and use it. From his family, his community, and his college classmates, Wade learned the importance of fighting for change by confronting the laws and customs that marginalized and demeaned people.

This powerful memoir reveals the struggles, joys, love, and ongoing resilience that it took to grow up Black in segregated America, and the lessons that carry over to our fight for a better future.

An Excerpt fromDefiant

Chapter 1

Civil Rights and Protests

So this is what solitary confinement is like? I asked myself, shaking my head.

There was no one else in the tiny eight-foot-by-eight-foot cell to hear me. A small sink near a toilet stood out. There were no windows. A thin mattress with a sheet and a blanket thrown over it rested on the concrete floor. There was no pillow.

I had thought the dormitory rooms on the campus of Southern University, the institution that I attended, were small. They now seemed like large suites at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City compared to this suffocating place.

I sat down on the mattress and leaned against the brick wall. I didn’t know what was happening. Why had a warrant been issued for my arrest? I hadn’t done anything illegal!

A little more than an hour earlier, I had been in a car with two friends, on our way to a grocery store. With the windows rolled down, we were enjoying the nice spring breeze that blew into the car and cooled us off. The latest R & B hits played loudly on the radio. Suddenly, a news flash interrupted our groove and caught our attention.

Two Negro men were arrested this morning in the Scotlandville section of Baton Rouge. They have been identified as Alphonse Snedecor and Frank A. Stewart. Both men are wanted for conspiracy to murder Baton Rouge mayor Woody Dumas and a number of other city officials, authorities said. A press conference will be held later today, when more details will be disclosed. A third man identified as Wade Hudson is being sought, authorities added. Both Stewart and Hudson are leaders of SOUL, a civil rights organization with headquarters in the Scotlandville section of Baton Rouge. Snedecor, a Baton Rouge native, is also a member of the group.

No one said a word as the music began to play again. It was as if the world had stopped.

James Holden, Stewart’s cousin and the owner and driver of the car we were riding in, slammed his open hand hard against the steering wheel.

“What the . . . !” He didn’t finish the sentence.

“Damn! Damn! They must have picked up Frank just after we left. This is bad.”

“Who else they gonna arrest?” Barbara George, the third member of our trio, asked. The fear in her voice was apparent.

I didn’t say anything. Staring at nothing in particular, I began thinking about all the other young Black freedom fighters around the country who had been arrested or killed. I had even donated to fundraising efforts for many of them. I thought about Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, Black Panthers leaders who had been killed a few months earlier by the police in Chicago. Would Frank, Alphonse, or I become three more casualties?

“Holden! Take me to the bus station,” I blurted. “I gotta get out of Dodge, man! I gotta get out of town. These folks will either kill me or send me to prison for the rest of my life. I got to get out of here!”

Holden pulled over to the side of the road and stopped the car. He and Barbara looked at me.

“That’s what you want to do?” Holden asked pointedly.

“Yeah, man, I’m splitting! These are crazy White folks! I don’t know what they’ll do. You heard what the man said on the radio. They’re accusing us of trying to kill the mayor and some other White officials.”

“But you can’t go to the bus station,” Barbara interjected. “Cops are probably there, too, and at the airport.”

“Well, drop me off at the bus station in Cheneyville or some other town not too far from here. I ain’t going to jail for the rest of my life!”

I looked around, now concerned that the police might be closing in on us.

“Wade, if you run and they catch up with you, they’ll shoot you. I’m telling you. They’ll shoot you.”

“Barbara is right,” Holden added. “They already got Frank and Alphonse. If they do catch you, it’ll just look like you’re guilty. Frank ain’t guilty. He wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

“That don’t matter!” I shot back quickly. “They’re just trying to get us out of the way. They’re trying to kill the organization. They’ve been doing this across the country. We’ve been pushing voter registration and trying to get Black people to vote. If more Black people vote, we can get these White, racist politicians out of office, and they know that. They don’t want Black people to have any power.”

Frank Stewart and I, along with a small group of other community activists who were mostly students at Southern University, had formed the organization we named the Society for Opportunity, Unity, and Leadership. Its primary purpose was to deal with conditions in the Black community caused principally by racism and discrimination. We called the group SOUL. Barbara was a member. A veteran of the Vietnam War, Alphonse had joined, too.

SOUL had started a breakfast program to feed hungry kids, established a small library of Black books, and conducted rap sessions where conditions in the all-Black Scotlandville neighborhood were discussed. We were beginning to move into the political arena, too, encouraging people to vote. Some of our members had begun wearing berets, like the Black Panthers did.

“I think you should turn yourself in so y’all can fight this together,” Barbara suggested.

“What?! Turn myself in? You got to be kidding, Barbara! Man, this is crazy.” I forced a laugh, but the situation wasn’t funny. It wasn’t funny at all.

“Even if you’re able to get away and make it out of the country, you won’t be able to come back.”

I thought about what Barbara had said. If I couldn’t come back, that would mean I wouldn’t be able to see my family anymore, or all the people I knew and loved.

“You think I should turn myself in, too?” I asked Holden.

“It’s better than being dead! These White folks will shoot you!”

I let out a chestful of air. As the three of us sat there in that car for what seemed like forever, I considered next steps. It all seemed so surreal. No, unreal. I’d known this could happen, that what we called the racist White power structure in Baton Rouge could pounce on us one day. The truth was, we were fortunate it hadn’t happened sooner.

“Y’all really feel I should turn myself in?” I asked again, seeking assurance.

Neither Barbara nor Holden answered. The looks on their faces said it all.

“Okay! Let’s do it! Let’s get it over with!”

The music, now at a lower volume, played in the background as the car moved slowly toward downtown Baton Rouge.

“I’ve never seen you drive this slow, Holden. You scared?”

“You damn right!” He laughed and said, “You don’t want them to stop this car and pick you up before you can turn yourself in, do you?”

The parking area at the East Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff’s Office was packed, but we found a spot. After walking into the building, we headed for the counter where a heavyset White man in uniform sat. I stepped forward.

“Can I help y’all?” the officer asked in his Southern drawl without looking up from his notepad.

I looked at Barbara and at Holden, then turned to face the officer again.

“I’m Wade Hudson,” I told him.

“So?” he responded condescendingly.

“I understand there’s a warrant out for my arrest. Hudson, Wade Hudson.” I repeated my name.

My name finally registered with him. He jumped up from his chair and called several other officers over.

“This is the third one,” he told them.

The officers pushed me against the counter, forced my arms behind my back, and handcuffed me. As they led me away, I looked back at Barbara and Holden just in time to see Holden thrust a raised fist into the air.

“We’ll get a lawyer for you, Wade!” Barbara said. “Hang in there.”

After being fingerprinted and photographed for a mug shot for the first time in my life, I was taken to this small cell in the basement of the jail.

Since my incarceration began, I hadn’t seen anyone except police officers and several detectives who came to stare at me through a small window in the door of my cell. I knew nothing about the charges I was being held on. I was completely in the dark.

The brick wall that I was resting my head against started to give me a headache. I decided to try the thin mattress, but it wasn’t much better.

I couldn’t help but wonder whether this was the end for me. Conspiracy to murder the mayor and who knew who else? How could I ever get out of a fabricated frame-up like this?

It had been a little more than five years since I’d left my home in Mansfield, to attend Southern University. It seemed so much longer. A lot had happened during those years.

At home when I was growing up, I had followed the civil rights movement and the events that unfolded in the South and around the country. I wanted to be involved. I wanted to make my own contribution, take my stand for freedom, just as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Daisy Bates, Stokely Carmichael, and Rosa Parks were doing. I yearned for the opportunity to confront the evils of Jim Crow segregation that forced the people I knew and loved to be subservient to White people.

Mansfield, however, was like thousands of other small rural towns across the South that White people controlled virtually unimpeded. Fighting against their system of oppression often resulted in lost jobs, being run out of town, or, worse, being killed. These were enormous prices to pay. But I wanted to fight back; I burned to do something about the evil that haunted my people.

So, you might say that my experiences in Mansfield led me to this place. How I grew up there, how those impactful years shaped me, all pointed me toward a future I had to embrace. Even if it led me to jail.