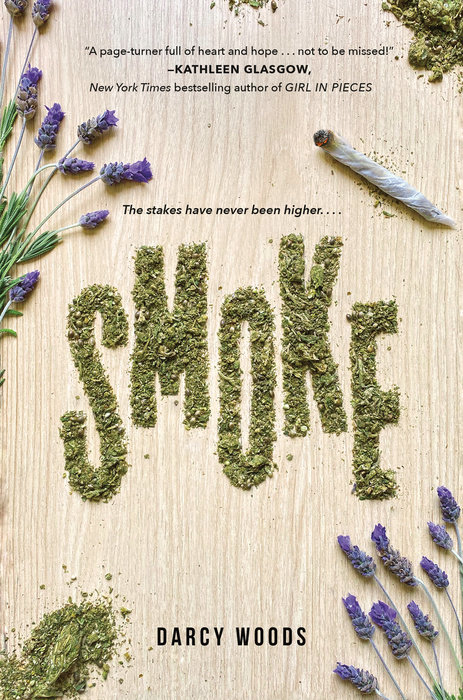

Smoke

What lines would you cross to save someone you love? Filled with the kinds of impossible choices that made the TV show Weeds such a hit, this compelling drama asks to what lengths an avid rule-follower will go in order to save her family--and the answer involves "growing" in surprising directions.

Sixteen-year-old Honor Augustine never set out to become a felon. As an academic all-star, avid recycler, and dedicated daughter to her PTSD-afflicted father, she's always been the literal embodiment of her name. Coloring inside the lines is what keeps Honor's chaotic existence orderly.

But when she discovers her father's VA benefits drying up, coupled with a terrifying bank letter threatening the family's greenhouse business--Honor vows to find a solution. She just doesn't expect to spot it on the dry erase board of English lit--"Nature's first green is gold."

The quote by Frost becomes the seed of an idea. An idea that--with patience and care--could germinate into a means of survival. Maybe marijuana could be more than the medicinal plant that helps quiet her father's demons. Maybe, it could save them all.

An Excerpt fromSmoke

1

Sometimes you feel the whisper of a storm before it hits. Smell the tang of ozone as it punctuates the air. Watch the once-lifeless hair on your arms rise like the dead. The energy, the charge, it becomes a real and palpable thing.

But other times, like tonight, you sense nothing.

No whisper.

No warning.

And it’s of little consequence to the storm whether or not you’re prepared. Because, either way, it’s coming.

Lightning carves jagged marks across the sky. My attic bedroom explodes with brightness. I squeeze my eyes tight, willing the storm to pass. Praying for it to pass. But the foreboding zigzag pattern that lingers behind my eyelids kills those fragile hopes. My pulse gains speed.

One Mississippi. Two Mississippi. Three Mississippi . . .

I get all the way to seven Mississippi before the deafening crash. Thunder punches like a fist through the atmosphere, pounding against the earth. The powerful echo carries inside my body, reverberating through every limb.

By my count the storm’s about a mile away and closing in.

Dread sinks into my skin, takes residence in my bones. My fingernails, barely long enough to scratch an itch, dig hard into my palms. Because I know what comes next. And it’s a force as unstoppable as the storm.

This is going to be bad.

I fling back the covers, my feet hitting the rug as the sloped walls flare again with light. Seconds later the boom of thunder hits.

And a scream follows. Just like I knew it would. I feel the cry like it’s borne from my own throat.

I race down the narrow staircase to the second floor, where Geronimo paces. He whines, scratching at the bedroom door as the sky breaks open to release its sadness. Tears tick against the hall window like tiny pebbles.

“I know, Geronimo. I wish I could make it stop, too.”

Our beloved boxador—boxer-Lab mix—knows I’m not talking about the rain.

“Stay back,” I say into his good ear, giving his frayed collar a tug. “You can’t help him this time.”

Geronimo whines again in response, blinking his helpless onyx eyes before reluctantly backing away.

I open the door to where my father lies, painted in shadows, imprisoned by a past that stays all too present.

His breath erupts in sputtering gasps. “Foxtrot niner two seven . . . Bravo Company under attack. Repeat, Bravo—” His chest hitches before unleashing another bloodcurdling cry. “Noooo!”

“Dad!” I lunge to his side, where he’s tangled in sheets. “Dad, wake up!”

He doesn’t hear me. I grip his arms in hopes of tethering him back to reality. To this reality. But he’s too strong; the muscles the military trained into him never left. And his skin is too slippery with sweat to keep hold of him anyway. My father’s face contorts in agony as he thrashes away, knocking a picture frame from the nightstand. It clatters to the floor.

“Dad, it’s Honor. Listen to my voice. Whatever you’re seeing isn’t real. Not anymore. Wake up. Please, you have to snap out of it!”

His sparse bedroom is illuminated with pulses of light, glancing off the brass latches of the footlocker at the end of his bed. Ancient windowpanes tremble with the battle cry of thunder. A battle cry that transforms an ordinary storm into the terrifying sounds of warfare. Atmospheric cracks become the pop of rifles, while thunder detonates like bombs.

My father’s eyes are open now, but they don’t see me. They see the Iraq War. Tears slip from the outer corners of his eyes, held captive by silvering sideburns. “His leg . . . I found his leg.”

My heart throbs with a dull, all-consuming ache. I hate this. Hate seeing him lost in the dark place I can’t reach him. The room empties of air. When I go to swallow, a fist feels lodged in my throat. Hold it together. You cannot fall apart.

So I take a slow, deliberate breath. Try once more. “You’re safe now, Dad. You’re home. Far away from the—”

“You’re gonna get yourself hurt again, Honor,” Knox groggily mutters, clicking on the lamp on the dresser. But even with the light, the shadows in the room are smothering. “I got Dad. You roll.” My brother staggers across the room, still in yesterday’s jeans and T-shirt, and flops beside me on the bed. “Go on,” he says, before turning toward our father, who’s now curled away from us, whimpering like a wounded animal.

If I could claw the sound from my ears, I would. Focus on something. Anything else. “You reek of cheap beer,” I tell Knox.

“Yeah? You reek of sad. Trust me, cheap-beer smell’s an improvement.”

“Whatever, Knock Knox.” Not sure why I choose this moment to call my brother by the nickname I haven’t used since I woke up crying from my own nightmares, but here we are. Only this time, my brother can’t chase away these monsters with terrible jokes.

Knox jerks his chin toward the dresser, then resumes coaxing our father back from the abyss.

Opening the top drawer, the drawer that used to be Mom’s, I remove the old cigar box and plastic baggie inside it. I shake out what’s left of the dried bud, breaking off tiny nuggets of leaves, plucking away the stems. This is the only thing I know to do that helps in the aftermath of these episodes. Which is why I’ve gotten so good at it.

Somehow the ritual calms me, quelling my hyperactive heart, soothing my fraught nerves. Ironic I should find the same relief in the simple act of rolling a joint that my father will have in smoking it. But there’s comfort in the way my fingers know what to do without being told. Following one step with blissful surety into the next. Knowing that the outcome will be the same even as the sky falls around me.

“Honor?” Dad rasps, sitting upright. He rubs his eyes and sees me, for real this time.

And it doesn’t matter that my brother’s buzzed. He is, and will forever be, the PTSD Whisperer when it comes to our father.

“I’m here, Dad,” I reply, filling the crease of the rolling paper with bits of pungent green. And with painstaking care, I roll the most perfect joint imaginable. Tight. Fat. No holes for smoke to escape.

My father cradles his head, running his hands along his shorn hair as his breath steadies. “Did I hurt you?” He looks up. Worry deepens the faint grooves in his forehead. “I couldn’t handle it if I hurt you or—”

Knox squeezes Dad’s shoulder, putting a tourniquet on his words. He has our father’s hands, large with pronounced knuckles. Although my brother’s hands don’t have calluses and scars from years of manual labor like our father’s. “She’s fine, Dad. We’re both fine. That was the nightmare talking.”

“I’m fine,” I repeat firmly. For my own sake as much as his.

His color slowly returns—shifting from chalk white to deep tan, the result of countless hours of construction work. “Thank God,” he murmurs. “I’m . . . I’m sorry you had to see that. Again.”

“Dad . . .” A sharp twist of pain prevents me from saying all the things I wish I could say. But he’s not—might never be— in a place to hear them. To hear it’s not his fault. That he didn’t choose to be sent to some war-torn desert thousands of miles from home. That his struggles don’t make him weak. Quite the opposite. My father’s one of the strongest people I know.

But in the end, all I can manage is a quiet “Please, don’t.”

Last year, right after he and Mom split, Dad suffered one of his worst night terrors. Which is how I wound up with a hellacious black eye. He didn’t remember a thing. So Knox and I concocted a fantastical tale involving my face and a wayward baseball. Plausible given my complete lack of athletic ability. Then I wore sunglasses the size of satellite dishes until the bruise turned sunshine yellow.

“Need to use the head?” Knox asks in his easy way, giving our father’s back a gentle clap.

Dad wipes his face and nods. Squinting at the clock, he says, “It’s after one in the morning. Don’t you two have school tomorrow? You should be in bed. Go on now. Your old man can take care of himself.” He trembles as he rises, checking to see if we notice.

We feign oblivion.

Dad ruffles Knox’s hair like he’s five, repeating the gesture as he passes me. The action’s meant to convey everything is fine.

But it isn’t.

Geronimo’s tail thumps the wall like an enthusiastic battering ram as Dad steps into the hall. That dog would surgically attach himself to my father if he could.

I wait until I hear the bathroom door close. “I feel like he’s getting worse.” I sink down beside Knox on Dad’s bed of bricks.

“Yep.” My brother catches a burp in his fist and stretches out his long legs. His big toe peeps out of the hole in his sock like a fleshy periscope.

“You think there’s something else going on? Besides the storm.” With PTSD, the trigger could be anything—sights, sounds, smells . . . even feelings that associate with a trauma.

Knox sways a little as he ponders. “Dunno. He’s been a little quieter. Spending more time in the barn than usual.”

Something I noticed, too. I anxiously twist the ends of the joint. “What am I going to do when you leave for college this fall? I mean, how will I handle Dad?”

“I hear scientists are making major headway with clones. Imagine a world with two of me.” His dark brows bounce up and down. “Utopia, right?”

I jab him with my elbow. “This is important. Can you at least try to be serious?”

“Is this a trick question?” He snorts at my stony expression. “I swear to God you were born like eighty years old.” Knox curls his hands into fists, rubbing his eyes like a sleepy toddler. “Look, it’s just community college, Hon. I’ll be living half an hour from home. Not like I’m headed off to some faraway, fancy Ivy League school with gold-plated urinals.”

The water pipes let out a soft moan, the sound overlapped by the scrape of the shower curtain along its rod.

Guilt stabs me in the belly. While my brother’s never had the academic prowess for the Ivy League, it’s the mention of “faraway” that’s piercing. Because Knox traded his dream, reflected in every snowcapped mountain poster on his bedroom wall, to stay here in northern Michigan.

You could still end up in Colorado, I want to say. Working at a resort and snowboarding your heart out. But the reality is my brother doesn’t postpone. He either does things or he doesn’t. And that’s not a character trait I can reverse tonight.

“But you won’t be here,” I add. “So you have to tell me exactly what you say to Dad. I must be doing something wrong, because he never comes out of it when I try.”