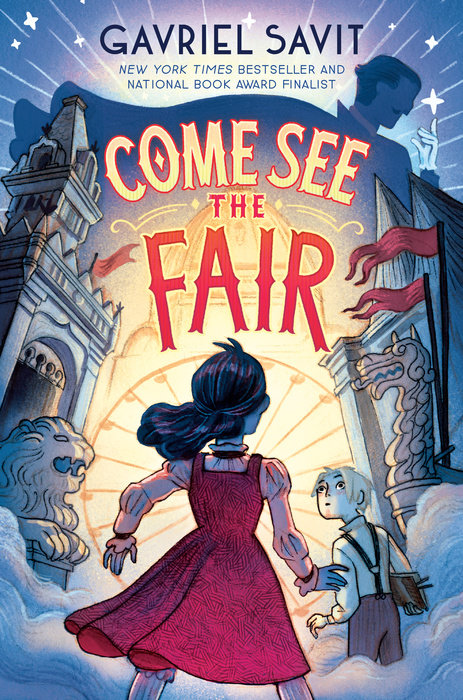

Come See the Fair

Now in paperback! A story of what to do when you get burned by the magic you’ve been looking for all your life from the author of the National Book Award finalist The Way Back.

Twelve-year-old orphan Eva Root travels the country pretending to channel spirits at séances. Her audiences swear their loved ones have spoken to them from beyond the grave. This, of course, is impossible.

But one day, Eva experiences another impossibility: she hears a voice in her head telling her to come to the World’s Fair in Chicago. There, she meets a mysterious magician who needs her help to bring magic to life. But as their work progresses, Eva begins to suspect that the project's goals may not be as noble as they seem. And when tragedy strikes, Eva will have to reach beyond death itself to unravel the mystery of the magician's plan—before it’s too late.

An Excerpt fromCome See the Fair

1

Strange Fire

Mrs. Jenny Blodgett

presents:

the amazing

Little Eva Root

Clairvoyant!

Spirit Medium!

Channeler of the Voices of the Dead!

Her Uncanny Abilities shock the senses!

She brings forth the Messages of the Departed!

Come and see!

Come and See!

COME AND SEE!

During the first week of June 1893, these handbills were unavoidable in the village of Nadab, Ohio. Mailed ahead, they were as common as coal dust by the time Mrs. Blodgett and Little Eva arrived--piled by the door at the Hofmann Emporium, boot-trodden and filthy on the floor of Wilson’s Saloon--and wherever Mrs. Blodgett encountered them, she bent to add the following lines:

Wednesday at 8:00

Back room at Wilson’s

35¢

Just. Like. Magic.

It began--as everything does--with a spark.

Mrs. Blodgett had started drinking early that day, and her hands shook as she struck at the matchbox: two times, three. A puckered woman on the front bench was fanning herself against the summer heat, and Mrs. Blodgett had to turn her back to the audience for shelter from the breeze.

With a final strike, the match head burst into flame. Glaring over her shoulder, Mrs. Blodgett lit the candle.

The presence of this candle, like so much of the evening, was theatrical: it allowed Little Eva to begin the performance by lifting the light out of the room like a grand curtain.

And séances are always better in the dark.

The truth was that Eva Root had not been particularly little in quite some time. Years before, when Mrs. Blodgett had first trotted her out, the description really had been apt--a tiny seven-year-old, wide-eyed, rosy-cheeked. But she was nearly twice as old now, and the passing days had stretched and sharpened her like the fires of a forge: every day a new town, every night a new bed, and in between, train car after train car after train car. By the time they found themselves in Nadab, they’d given well over a thousand séances in the little towns that had budded up from the steel boughs of the railroad--Carthage, Kansas; Finisterre, Iowa; Goshen, Nebraska--and though she no longer had the smoke screen of innocence to hide behind, Eva had learned all she needed to know about passing on the communications of the dead. Which, of course, was impossible.

But all the same--she had a way of making it seem as if it were not.

From the back of the room, Eva considered Nadab’s paltry little crowd. Not counting herself or Mrs. Blodgett, there were five of them there--more than had been at the smallest séance she’d given, but not by much. They were mostly old, too, which muddled things: the more one lives, the more one loses.

She took a deep breath. It wasn’t her favorite trick, but there was always the war to rely on: practically everyone over forty had lost someone who’d served in blue or gray.

Cannon fire, gun smoke, The Union forever, hurrah! boys, hurrah! . . . It was going to be that kind of night.

She flexed her fingers.

Someone in the slack, sweating audience let out a little fart, and this seemed to deplete Mrs. Blodgett’s already scarce reserves of patience.

“Fine,” she said. “Ladies and gentlemen, it is my privilege to present to you Miss Eva Root, a young innocent touched with the power to channel the voices of the dead. Kindly give her your attention, and in return, she will show you things that you never thought possible.”

This speech had once been considerably longer--and considerably better--but then Mrs. Blodgett had once cared.

“Eva?”

Five heads swiveled back to stare at her. She stumbled forward.

“There?” she said, blinking at the chair that had clearly been set out for her.

This performance of uncertainty generally made a better impression when Mrs. Blodgett responded in some way, but she had already begun to wobble gently around the room snuffing the gas lamps.

Swallowing, Eva slid into her seat. Soon only the flickering candlelight was left.

“It works better in the dark,” she whispered. “Can I . . . ?” and she gestured to the candle.

Her eyes passed slowly over the faces before her. This was the most important part of the evening, this moment of anticipation. She could make all the right guesses, say just the right things, and still, if these people didn’t want her to do impossible things for them, then she simply couldn’t.

The lady on the front bench gave a curt little nod--engaged, but not terribly enthusiastic. Three rows behind her, though, was a man with an unkempt beard who smiled kindly.

That was good: a foothold.

Eva pressed her eyes shut, leaned forward, and blew. The candle guttered and died.

Darkness.

Now she began to thicken her breathing with effort.

“I hear thunder,” she said. “Men yelling. There’s smoke. Fire.” She went quiet for a moment. “Is it . . . a storm?”

Somewhere in the room, a chair creaked.

“But there’s no rain,” she said. “No, not a storm.” Another little pause. “Is it thunder? Or . . . ?”

“Cannon,” said an eager woman in the third row. “It’s cannon.”

Eva turned her head immediately. “Yes.”

“Was he afraid?” said the eager woman.

To be sure, it would’ve been kinder to say that whomever this woman was thinking of had died without suffering. But that would’ve made for a rather duller séance. And besides--the more you agreed with them, Eva found, the more people began to believe you.

She nodded sadly. “There’s quite a lot of fear. But gratitude, too. He wants you to know that he thought of you before the end.”

“Me?” said the eager woman.

Eva chuckled. “He knew you’d be surprised.”

“Oh,” said the woman fondly.

Eva didn’t know whom they were talking about, of course, but it didn’t matter--the woman in front of her did, and her certainty filled in Eva’s sketchy outline with a memory so clear it almost seemed to breathe.

That was how it worked.

Eva spent a fair amount of time on the eager woman; she was well disposed to believe, and Eva had a tendency to make her guesses work even when they were a bit wide in their aim. By the time Eva moved on, the woman was sniffling softly: a job well done.

The lady in the front row came next. She was the sort who wanted to be won over--a little reserved, a little skeptical--but Eva, as always, was patient, and mere minutes later, she was forgiving the lady for her unkindness to a niece who (Eva was almost certain) had fallen to her death in a well.

And then, in a flash, everything changed.

Eva had just turned to engage the man with the unkempt beard when, with a spark and a sputter, the dead candle at her elbow flared back to life.

She made a sound somewhere between a gasp and a yell, and was on her feet before she knew it.

“What is it?” said the woman in the front row.

The candle was burning bright, its flame tall and unwavering. Eva wasn’t sure what to do. Nothing like this had ever happened before.

“Someone,” she said, improvising madly. “Someone is here with us.”

And this was truer than she knew.

“Who?” said the woman in the front row. “Who is it?”

Eva turned her eyes back to the audience. The candle flame gave a wobble, sending inky shadows vaulting across the expectant faces.

She still had a performance to give.

“That,” said Eva, gesturing with her chin, “is a question for you.”

The bearded man frowned. “Me?”

“Yes. Who is it?”

The bearded man took a deep breath and began to speak. Eva barely heard him.

Come see the Fair!

The voice in her head had spoken so loudly that the words of the bearded man had been entirely blotted out.

“What?”

“Why, I said my daddy always--”

Come see the Fair!

Eva gasped. Nearly half her life, Eva had pretended to hear messages that weren’t there. Now, all of a sudden, her mind was filled to bursting with an impossible voice.

At the back of the room, Mrs. Blodgett shifted uneasily from foot to foot.

“I--I--I . . . ,” Eva stammered. “Who?”

And as if in answer, she was overcome by a rush of sound nearer to her than anything had ever been before: the tinkle and bray of the band organ, the laughter and chat of the crowd.

An impossible voice, loud and commanding and clear:

Come see the Fair!

“I don’t understand,” said Eva.

The room was suddenly silent.

It was only a moment before Mrs. Blodgett swept forward, her face twisted with anger.

“I am afraid,” she said, “that Little Miss Eva is tired and must withdraw.”

There was a hubbub of protestation, but Mrs. Blodgett’s voice cut through it sharply.

“Thank you,” she said. “Thank you. Good night.”

And taking Eva roughly by the arm, she seized the candle, blew it out, and marched swiftly from the room.

When she first met Mrs. Blodgett, Eva Root was living in an establishment in Fletcher’s Gulch, Indiana, called Miss Augusta Grandage’s Home for Unwanted and Destitute Girls.

She had no memory of anything before that place.

The handlers at Grandage’s seemed to see themselves rather more as salespeople than caretakers: anything that bred attachment was strenuously discouraged, and the penalties for talking out of turn were severe.

But there were many worse institutions to be in. No one was violent or neglectful. Adoptions were frequent. Miss Augusta was rigorous, but generally benevolent.

When Mrs. Blodgett arrived that day, she asked that the girls be shown to her in a private room, one by one. Most of them were dismissed without a word, but those deemed promising enough to address were offered a single question:

“Do you remember me?”

Mrs. Blodgett had, of course, never before visited Fletcher’s Gulch; it would’ve been impossible, then, for any of the girls to say yes truthfully. Nevertheless, everyone who said no was immediately dismissed.

Eva happened to be one of the last shown into the room that day, and whispered word of what went on there had made its way back to her.

When Mrs. Blodgett asked her question, Eva was prepared.

“Oh, yes,” she said. “Of course I remember you.”

Mrs. Blodgett’s eyes narrowed, and taking sudden inspiration from a painting on the wall, Eva spouted an idyllic story about a picnic in the town square.

It was a complete fabrication--they both knew it. And this was precisely what Mrs. Blodgett had been waiting for: someone to convince her of the impossible.

The expectations were never directly articulated. Instead, Mrs. Blodgett had taken Eva to observe séance after séance, night after night, in town after town, and sometimes at the facilitation of the very same medium. Slowly, the tricks of the trade became clear--how to sow confidence; how to make the general feel specific; how to leave room for people to fill in their own details--and an audience began to seem to Eva like a craggy rock face, here a handhold, there a ledge.

And then, one night, leaving a little theater somewhere in Pennsylvania, Mrs. Blodgett had spoken.

“He wasn’t very good, was he? That medium.”

The medium in question had been an old man with gigantic sideburns, and he’d been far too prone to making real, specific guesses.

“No,” said Eva. “Not very good at all.”

“You’ll do better,” said Mrs. Blodgett.

The next night, Eva gave her first séance. She, it turned out, had something of a talent, and the people crowded around, wanting, needing, begging for her impossible answers.

They were so grateful. Soon Eva began to feel quite fond of her audiences.

But a structure built on a lie can only stand for so long. Eva’s fondness began to rot into resentment, then disdain, and before she knew it, her disdain had become a dull, tarnished pity.

It was the need that made her so sad, the constant need for something that simply wasn’t there. And if her audiences went home with the impression that they’d gotten what they paid for, she knew it could not last; in the morning they would wake again as lonesome and grief-stricken as they ever had been.

She was sure of it. She did herself.

Because the need that the people brought to lay at her feet every night was the very same need that Eva carried from town to town, village to village, séance to séance: the need for things to be different--better, brighter--than they were.

And this was why, as Mrs. Blodgett tore her from the saloon in Nadab, Ohio, Eva caught a strange feeling blossoming in her chest--strange, and deeply concerning:

It was hope.

Eva sat in silence, her shoulders high and tight, as if she were waiting to be hit.

No one in the audience at Wilson’s had been happy with the early ending of the séance, but Mrs. Blodgett had already arranged for a local drayman to cart them to their accommodations in the next town, and thankfully they were able to leave before anyone asked for their money back.

That was the greatest calamity that Mrs. Blodgett could imagine: paying refunds.

Crickets, hoofbeats, the creak of the cart; it was only once the lights of Nadab were far behind that Mrs. Blodgett took the candle from her bag.

Eva braced herself. Mrs. Blodgett didn’t so much have a temper, generally, as the temper had Mrs. Blodgett.

“How did you do it?” she asked.

“I didn’t.”

Mrs. Blodgett narrowed her eyes. “Don’t lie to me, girl.”

“I didn’t,” Eva insisted. “Did you?”

“Don’t be foolish,” said Mrs. Blodgett.

Eva leaned in to get a better look. “Is there anything--?”

Mrs. Blodgett shoved her away. “No,” she said. “It’s just an ordinary candle,” and she tossed it roughly into her bag.

The drayman’s lantern swung gently with the gait of his horse.

“Would you care,” said Mrs. Blodgett, “to explain that disgraceful display? Gasping and flopping about like a fish.”

“I was thrown.”

Mrs. Blodgett shook her head. “You’re never thrown. What happened?”

Eva took a breath. What could she tell her? What could she say?

Usually, Eva and Mrs. Blodgett ate their supper together after the séance. Tonight, though, Mrs. Blodgett ushered her into their little hotel room without so much as a crust of bread and stood there in the doorway, hands on her hips, just waiting for an objection. Eva stayed quiet--she had no interest in worsening the situation--but her silence only seemed to make Mrs. Blodgett angrier.

“I think,” she sniped, “that you ought to sleep on the floor tonight.”

In general, where there was only one bed, Eva and Mrs. Blodgett shared. This was no particular pleasure, but it was certainly more tempting than the rough wooden floor.