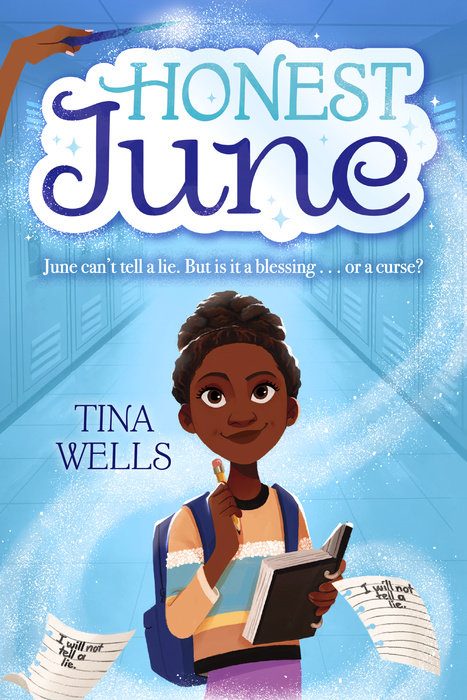

Honest June

Honest June is a part of the Honest June collection.

Who wouldn't want a fairy godmother? But when June's puts her under a spell where she cannot tell a lie, the truth is middle school just got a lot harder.

The truth hurts. Sixth-grader June Jackson learned that lesson early. (She told her BFF one time she didn’t like her shoes. They fought for a week!) Which is why now June tells people what they what to hear. Who cares about a small fib if it makes her friends and family happy?

But when June’s fairy godmother appears in a cloud of glitter, she’s grants June with the ability to only tell the truth. Now, June has no choice but to be honest about how she feels. And the truth is June feels stressed out. Middle school is no joke—between field hockey, friend drama, and her parents' high expectations, June is so overwhelmed that sometimes it’s hard to breathe.

When everything spirals out of control, will June find freedom in telling the whole truth and nothing but—or is she destined to battle the curse for the rest of her life?

An Excerpt fromHonest June

Chapter One

I don’t know everything about life yet, but I know at least one thing is true—life’s easier when you make people happy.

You want to get good grades? Tell teachers what they want to hear. Want your friends to like you? Tell them you love their clothes and their hair and their moms’ cooking. Want your parents to be happy? Do what they say. Follow their rules. Happy parents equals extra dessert and cool toys and fun vacations. And, most importantly, love.

Making people happy is what I’m good at. Sometimes that means not telling people the whole truth. Or telling them no truth at all. Not because I’m trying to be mischievous! In fact, I don’t like to make trouble—but it always finds me somehow. Like the time I tried to compliment my best friend Nia on a pair of shoes she was wearing. I said they made her feet look “too long.” She was mad at me for a week. I vowed to say only nice things about her feet no matter what.

Or the time I accidentally knocked over the mailbox when Dad asked me to take out the trash. Instead of walking it to the corner, I put the trash bag on my old wagon to roll it down the driveway. I had the wagon aimed perfectly at the mailbox to stop its roll, but it smacked into the pole harder than I expected, knocking the mailbox over at a forty-five-degree angle. Oops! I went inside and pretended nothing happened. But the next morning, Dad was furious. His eyebrows came together in the middle of his forehead. “Stupid garbage trucks! I’m going to find out who did this and get them fired,” he said. I stood there, silent. What if he found out it was me? Would he fire me as his daughter? I kept my mouth shut. He fixed the mailbox and forgot about it in a few days, thankfully.

Or the time my mother asked me if I knew what the “birds and the bees” was, and I told her the truth—“No. Should I?” This led to one of the most uncomfortable conversations of my life about boys and girls and babies and . . . ugh! I get the heebie-jeebies every time I think about it!

I’ve found in my brief eleven years on this earth that the truth isn’t always necessary. Tell people what they want to hear. Smile and nod. No one gets hurt. And that is how I planned to get through the sixth grade, through middle school, and through the rest of my life.

It was the Sunday of Labor Day weekend, two days before the end of summer vacation. But in Featherstone Creek, a suburb of Atlanta, the weather stays warm through fall—so it always feels just a bit like summer outside. Mom, Dad, and I got back home from our house at Lake Lanier, about an hour’s drive away, late at night—just in time for me to unload my bags, eat a spoonful of peanut butter, put on my pajamas, and immediately pass out. I don’t even remember if I brushed my teeth. I slept like I hadn’t slept for ten years, and I didn’t wake up until I heard the chime notification from Nia’s text on my phone.

NIA: You there? We’re coming at 5 p.m. today.

I jumped out of bed and got dressed. My best friends Nia Shorter and Olive Banks were coming over for one last summer barbecue before school started. We were going to celebrate as if it were our birthdays and New Year’s Eve combined. After tonight, we had only one more day of no homework, no teachers, no alarms to wake up to before . . . it begins.

“It” being our first day of the sixth grade and our first day at Featherstone Creek Middle School.

We were no longer grade-schoolers. This was middle school. Prime time. The big leagues. At FCMS, we needed to bring our A games. We needed to make a great—scratch that, legendary—impression from day one and live up to the legacies that our parents and grandparents had created for us. Or else our parents would be disappointed. Our neighbors wouldn’t like us. Teachers wouldn’t like us. Then colleges wouldn’t like us. And we wouldn’t get degrees. And then we wouldn’t be able to get good jobs, and we’d have no money or friends or husbands, and we’d be living on our parents’ couches forever, surviving on chicken wings and Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. And then we’d become embarrassments to our families. If, at that point, our families still claimed us.

Okay, maybe not all these things would happen if we didn’t rock middle school. I tend to overthink things sometimes . . . just part of my charm, I guess? I don’t really like Cheetos anyway!

I straightened up my bedroom, which was next to Dad’s office. I kept my room nice and neat so my parents wouldn’t be tempted to come in and rifle through my things, like my journals or my laptop or—gasp—my phone. If they thought I kept my room in order, they’d think I kept my life in order, too. I smoothed my sheets and comforter and arranged all the pillows from large to small against the headboard. I cleaned my desk and straightened my framed photos of me and Nia and me and my BFF Chloe Lawrence-Johnson, who I’ve known since I was a baby but who moved to Los Angeles with her family last year. I went into my bathroom and put away the bottles of leave-in conditioner and edge gel I used on my hair today to put it up into a high braided bun—my go-to hairstyle for a summertime barbecue. Tomorrow, the day before school, is wash day.

By the time I made it downstairs, my mom and dad were getting food ready for the barbecue. My dad, wearing an old Howard University T-shirt, stood at the kitchen counter over a huge platter of chicken covered with barbecue sauce. My dad is a lawyer. He went to school with Nia’s dad at THE Howard University, aka the Harvard of the HBCUs, aka the Mecca, according to Dad. He practically screams “H-U! You knowwwwww!” if anyone merely thinks about Howard in the same room as him. And has big plans for his little girl to follow in his footsteps. Every. Single. One. He runs a law firm together with Nia’s dad in downtown Featherstone Creek, with their last names on the front of their office building.

Dad wants me to either run his firm when he retires or head into politics, like Madam Vice President Kamala Harris (“H-U ’86!” my dad screams at any mention of her name). I like wearing and buying nice clothes, and I definitely love MVP Harris, but I don’t know how I feel about arguing with people all the time, which is what legal stuff seems to be about, at least to me. And those suits they wear in court. They’re so stiff and itchy! And lady lawyers have to wear pantyhose even on hot summer days in Atlanta. Meanwhile, I get uncomfortable in jean shorts in July sometimes!

My mom is a doctor who delivers babies for all the moms in town. She works a lot, but she also gets to hold babies all the time, which to me sounds awesome. Her entire family grew up in Featherstone Creek, and most of her family started businesses here in town. Her dad, my granddad, has a family practice on Main Street. He’s our family doctor and Nia’s family doctor. And the doctor for half of my sixth-grade class.

My parents always mean well—they want the best for me—and I want to make them happy. Because when they’re happy, the house is happy. We eat ice cream and go to the Crab Shack for dinner. And spend more time at our lake house, and my mom and I get our nails done together at the salon. And my dad laughs with his mouth wide open, and when he laughs, everyone else laughs. When my parents aren’t happy, there are rain clouds, and boiled brussels sprouts for dinner, and my mom calls me by my full name—“June Naomi Jackson!”—in a high-pitched voice, and my dad’s eyebrows come together on his forehead like one long, hairy caterpillar. The eyebrows scare. The. Life. Out. Of. Me.

So, if me playing field hockey, going to Howard, and being a lawyer are what’s going to make them happy, then that’s what I’ll do. Or at least I’ll say it’s what I want to do. But a girl has a right to her own opinions. And a right to change her own opinions, too. Even if she keeps them to herself, which I am very used to doing.

At 5:00 p.m. the doorbell rang. Mr. and Mrs. Shorter and Nia stood at the door. Mrs. Shorter held a large Tupperware bowl of potato salad for dinner. “Hello, June, how are you, baby? Oh, you’re getting so tall,” she said.

“Hi, Mrs. Shorter. My mom is in the kitchen.”

“Smells good back there,” Mr. Shorter said, giving me a gentle hug. Nia’s parents walked toward the back of the house. Nia put an arm around me. “Girl! I thought you’d never come back!”

“We texted every day I was gone!” I said. She and Olive and I texted multiple times a day, all through summer. We basically knew where each other was at every second of the day. Nia rolled her eyes and smiled. We both giggled and ran upstairs to my bedroom. I flopped onto the bed, and Nia followed me, placing her bag down next to her.

“Sixth grade,” I said. “Finally, a place where I can really express myself.” I could use different-colored gel pens for my homework. Explore creative writing, join the school paper, really voice my opinions on big issues, like going vegan and saving the animals. Maybe I’d run for student body president. And I could even buy my own lunch! Freedom—I’d literally be able to taste it. “I’ll be glad to get out from under my parents’ wing,” I said.

“You act as if you’re going off to college,” Nia said. “They still feed you and give you an allowance.” Ugh. She was technically right. But at least I could choose one of my own daily meals at school! That would be a taste of freedom—it had to count for something.

“Did you read the books on the summer reading list?” I asked.

“I only made it through one,” Nia answered.

Typical! I thought. “Which one?”

“The shortest one. Something about the guy with the dog. It said the reading was optional.”

“Optional, but encouraged,” I said resolutely. I chose to read half the books on the list, though they, too, were the shortest ones. Even if teachers weren’t assigning the book list as a requirement, it could only make them happy to know you did some of the reading. It might help me get in good with these teachers from the beginning. I could use all the early bonus points I could get.

A knock on the door interrupted our conversation. “It’s me,” Olive called out. “Sorry we’re late. Mom couldn’t decide what to wear. What’s going on?” she asked as she opened the door, walked in, and plopped onto my bed.

“We’re talking about school,” I said.

“Yeah? I’m excited. Orchestra starts up again next week. I learned how to play Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It’ on the viola this summer.”

“On to the most important topic,” Nia interrupted. “What are you going to wear for the first day?”

I stood up and threw open the doors to my closet. Mom and I had gone shopping for new clothes the week before we went to Lake Lanier. She took me to the same stores where she’s bought clothes for me since I was four.

“This would look so cute on you,” Mom had said, holding up a pleated skirt with a printed pattern of teddy bears with their paws in honey jars. It looked like what preschoolers in the Alps might wear as part of their school wardrobe. I hated it.

I clenched my teeth. “It’s cute, Mom, very cute.” She tossed it into the shopping cart. I groaned internally, but I figured if I let her pick out one thing she liked, maybe I could get what I really wanted.

I wanted to go to stores that aligned more with my sense of style. This place called Fit sold women’s clothes and accessories and just about every item I’d seen on some influencer or celebrity on Instagram. I pointed to a dress on a mannequin in the store window as we passed by. “I saw this dress on that dark-haired Disney Channel actress you like, and she’s my age.”

“Yeah, but she’s an actress, playing a role. You are in sixth grade, and I don’t know if I want you wearing that. It’s a bit . . . mature.”

“That’s the point,” I said. “I’m a bit mature now.” I’m in sixth freaking grade! I am almost in a training bra! Can’t she see I’m practically a woman?

I walked inside. There was a black sleeveless blouse with a large bow at the neck that could pair with everything in my closet and still make me look sophisticated, even with that horrible teddy bear skirt my mom bought. But I really wanted to wear it with the pair of distressed jeans on display that had a few holes around the knees that . . . oh, look at that . . . came in my size.

She ended up buying me the blouse on the condition that I wear a sweater or jacket over it. She got her baby skirt, and I got my blouse. Everybody was happy. Compromise.

“So, the first day of school,” Nia said. She and Olive looked at my clothes hanging neatly in my closet. “Are we doing the skinny jeans with the oversized T-shirt thing? Maybe with those Air Force 1s? Or with a shiny ballet flat? You need something that will really make a statement on the first day.”

“I want something that says I’m . . . interesting,” I said thoughtfully.

“Soooo, black on black on black?” Nia smirked.

“Or maybe a caftan?” Olive said.

“A caftan?” Nia asked.

“Yeah, like what my grandmother wears exclusively from April through October. She says they let her skin breathe,” Olive said. “Whatever that means.”

“Fashion inspiration from your grandmother may not be a good first look for the sixth grade,” I said. We would have two-point-five seconds to make an impression on our fellow students and teachers at Featherstone Creek Middle School that would define how people saw us for the rest of our lives. At least that is what my dad told me about first impressions.

“Nia, what are you wearing?” Olive asked.

“Probably a skirt and my new denim jacket. Took me forever to get those rhinestones glued on, so you better believe I’m going to show off my work.”

Man, why couldn’t I design my own clothes, like Nia? What if I had the potential to be the next great American fashion designer like Vera Wang or Zac Posen and I’d never know it because my mom still picks out my clothes? All that potential, undiscovered. We were doing the world a disservice by not letting me pick out my own clothes!

“Girls! Food is almost ready!” my mom called from downstairs.

Nia and Olive moved toward the closet and quickly ruffled through my clothes. Nia found a white Vans T-shirt. “Pair this with that black denim skirt and you’re set.”

“Done,” I said. “Statement made. Says ‘sixth grade, here I am.’ ”

We gave each other high fives, then went downstairs and walked toward the back of the house for dinner.

The sun was getting low in the sky, and the fireflies were just starting to make their appearance as we all gathered around the large picnic table on our patio for dinner. Olive, Nia, and I sat on the far side of the long dining table. Dad placed platters of grilled chicken and steaks in the middle of the table, along with big bowls of potato salad and fruit salad.

“Dig in, fam,” Dad said. Several hands reached eagerly for the food. My mom kicked off the conversation. “Girls, are you excited for sixth grade?”

“Yes,” we said in unison.

“I know that June is looking forward to field hockey,” Dad said. That wasn’t exactly true. He was excited for me to play field hockey. I had never even played before. But I went along with team tryouts because it made him happy. If I told him I didn’t want to, he might think I was defying him. And then, I’d get the eyebrows. Must. Avoid. The. Eyebrows. “Do any of you girls play sports?”

“I’m going to play basketball again this year,” Nia said.

“And I’m still in dance,” said Olive. “And I play viola in the orchestra.”

“Wonderful,” my mom responded. “June, I wished you would have taken up ballet when you were younger. It always looks good to the private schools when you have some sort of performing arts background.”

“Yeah, Mom, but hard to squeeze in ballet between those field hockey practices,” I said, half joking, trying to butter up my dad.

“Sixth grade,” Mrs. Shorter said. “I can’t believe that these babies are in sixth grade already. Where does the time go?”

“Howard’s just around the corner,” my dad joked. I smiled, laughing along as if I were cosigning his college prep plans. Howard’s not a bad choice. But it’s also not the only choice.

Dinner continued, with the conversation finally breaking up between the sixth graders and the adults. As the bottoms of everyone’s plates became visible again, my mom announced, “Who wants cake?”

At our house, every Sunday dinner in the summertime ended with Mom’s 7UP cake. It’s a Southern tradition. A Jackson family tradition. A tradition I could easily pass on. The cake was a bit dense for my taste. But I didn’t dare tell my mom that. Telling your mom her dessert is bad is basically telling her you don’t love her. Or to never make you a cake again. I like cake. And I love my mom. So I lie.

My mother cut thick slices for my friends. They grabbed their forks and dug in. “June?”

“Yes, Mom, thank you! You know how much I love your cake!” I said. Mom placed a slice in front of me. I stabbed at the heavy slice until it turned into a mound of crumbs. I took a few bites just for show and tried not to grimace. The sugary icing wasn’t too bad, though.

“How’s the cake, girls?”

“Great, Mom,” I said. She smiled. I smiled. Smile and nod, June. Smile and nod.

The adults lingered around the picnic table until the sun dipped below the tree line and darkness set in. The lightning bugs danced around our backyard with abandon, and Nia, Olive, and I skipped through the grass, laughing and singing along to our favorite songs until the parents said it was time for Nia and Olive to go.

“I don’t want to say goodbye,” I started to whine loudly. I felt the emotions bubble up.

“It’s not goodbye, it’s see you later,” Olive said.

“It’s ‘see you in two days,’ June,” Nia said. “Get a grip.”

We gave each other a group hug. “See you then,” I said.

Dinner was over. My time to run free, laugh, dance around, and be silly would soon be over, too. In two days I’d have to grow up, put on my game face, and become a poised young woman entering a more mature phase of her life. It was time to get serious. Sixth grade was almost here.