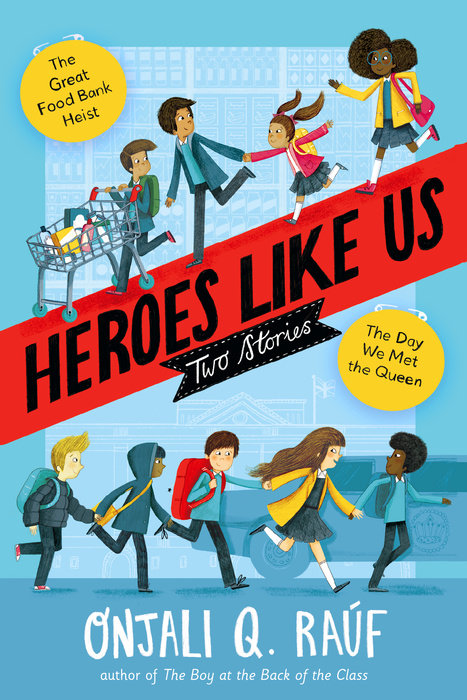

Heroes Like Us: Two Stories

From Onjali Q. Rauf, acclaimed author of The Boy At the Back of the Class, come two poignant tales of modern-day heroism, featuring supermarket theives, a visit with the Queen, and plenty of laughs!

Ten-year old Ahmet, once known as the "Boy at the Back of the Class", became the Most Famous Refugee Boy in the World when he and his friends stood up for refugee children like him all over Britain. But they're just getting started!

THE DAY WE MET THE QUEEN

Ahmet and his friends have been invited to tea—by none other than the Queen of England herself! But when their journey is unexpectedly interrupted by an old enemy, it will take some quick thinking and an ingenious plan to make it to the palace—and the queen—on time.

THE GREAT FOOD BANK HEIST

On Thursdays, Nelson, Ashley and Mum head out to the food bank. With its shining cans and boxes of food stacked from floor to ceiling, Nelson thinks it’s the best kind of bank there is. But there’s a thief in town, and the shelves of the food bank are getting emptier each day.

One thing is for certain: someone has to put a stop to the robberies. And Nelson and his friends plan to do just that, with a daring supermarket stake-out that's sure to catch the Food Bank Theives—if they don't get found out first!

In this two-novella collection, discover kid heroes making a difference in the world, featuring old friends and some new classmates you won't want to leave.

An Excerpt fromHeroes Like Us: Two Stories

1

A Very Royal Assembly

“Can you believe it? Can you believe we’re going to see the Queen tomorrow in actual real life!”

I looked at Michael. We were standing by the bus stop, waiting for Tom and Josie. Michael pushed his glasses even farther up his nose and, holding the card to the light, stared at it hard--just like shopkeepers do when they think your money isn’t real.

But we both knew the invitation was real.

The card was so thick it wouldn’t let any light through. The writing was fancy and swirly and there was a thick blob of shiny red wax on the envelope. All those things reminded us that the actual real-life Queen of England had sent it and was expecting us to join her for tea tomorrow.

I got my own invitation out from my backpack and held it up to the light too. Not because I wanted to check if it was real but because I wanted to look as important as Michael did. Holding stuff up to the light always makes things seem more serious and scientific than just looking down at them in your hands. I guess that’s why people in detective shows on TV are always doing it, even when the room they’re in is dark, and holding something up doesn’t make a single bit of difference.

“Hey!” called Tom as he hurried toward us. Josie was following him and waving as she dribbled her football. Tom’s blond hair was so spiky today it made his head look as if lots of tiny, shiny pyramids had suddenly sprouted up on top of it. Josie’s red hair was in a short, thick braid, which looked like a piece of twisted boat rope that someone had cut off in the middle. You knew it was an important day if Josie’s hair was in a braid, because she hates her hair being touched or brushed almost as much as she hates beetroot.

“You look . . . different,” said Michael, staring at Josie’s hair as if he wasn’t quite sure what she had done to herself.

Josie shrugged. “It’s for the assembly. Mum and Dad promised me tickets to the West Ham game next week if I let them braid it, so I thought I might as well. Even if it does make me look stupid. I mean, look at it!” Grabbing the end of the braid, she pulled it around the back of her neck and over her shoulder to try and make it reach her mouth. But it was too short. “What’s the point of it?” she asked, shaking her head. For Josie, hair existed for only one reason--so you could suck on the ends of it when you were nervous or needed help thinking. And to do that, hair needed to be loose and free--and unbrushed.

“Did you bring your invitations?” I asked.

Tom nodded and reached up to check that his hair was still super spiky. “Mine’s in my bag. But . . .” Dropping his arms, he scowled and added in a whisper, “Mum framed it!”

Josie snickered. “What? What for?"

“I don’t know.” Tom shrugged. “She said anything from anyone royal should always be framed. Especially something from the Queen. She even framed the envelope!”

“Oh . . . ,” said Michael, looking down at his frame?less invitation as if it was suddenly a dis?appointment.

“Do you have the list of questions?” asked Tom, looking at me.

I nodded and patted my backpack. Ever since we had known we were going to have tea with the Queen of England, me and Tom and Ahmet and Michael and Josie had spent nearly every break time writing down all the questions we wanted to ask her. In the end, we had fifty-two questions ready, but then our teacher, Mrs. Khan, had said maybe we should cut it down to just two questions each--because the Queen was nearly one hundred years old, and being asked fifty-two questions might make her fall into a coma. Now we were going to read out the questions in morning assembly and show everyone our invitations and explain why we were going to see the Queen. It made my stomach feel funny every time I thought about it.

“Bus is coming!” said Josie, picking up her football and joining the long line of people in front of us. I put my invitation away carefully between two of my workbooks and, quickly zipping up my backpack, jumped on board the bus to school. Running up the stairs, we made our way to the front seats.

“Hope Ahmet remembers to bring his invitation,” I said as I squished up next to Tom. “Do you think his foster mum will frame his too? His is probably even more special than ours.”

Tom shrugged. “Maybe . . .”

“Anyone else really nervous?” asked Josie, pulling her braid again and trying even harder to make it reach her mouth. “I keep worrying I’ll forget everything. I hate assemblies . . .”

Me and Michael and Tom fell quiet, because we were all starting to feel nervous too. None of us had ever been asked to get up in front of the whole entire school and speak at an assembly before.

Usually, assembly was the best part of the day--because you could just sit and pretend to listen even if sometimes you weren’t listening at all. Even the teachers like assembly because they don’t have to be working or trying to keep everyone under control. You can tell that teachers love assembly more than anything else because they always want to get there early and then when it starts, they sit and smile as if they’re thinking about something much more fun than what they’re actually listening to.

But today, instead of Mrs. Sanders, our head teacher, staring out at us through her big, square glasses, me and Tom and Josie and Michael and Ahmet were going to be the ones onstage in the huge main hall. All because the Most Famous Woman on the Whole Entire Planet had invited us to her palace for tea.

And that was because of Ahmet, the Most Famous Refugee Boy in the World, who had not only let us be his friends but had made every single one of us almost as famous as he was. Just because we had tried to help him find his family and stop the Queen and the government from closing the gates and borders to refugees like him. I hadn’t thought any of those things would make us famous. But for some reason, grown-ups get excited about things that should be normal, and that makes you famous somehow.

“As long as I don’t forget what I’m supposed to say and go blank, I don’t care what happens,” said Tom. “There is nothing worse than going blank! One time, back in New York, I was supposed to sing the national anthem on my own--and I went blank for so long I got booed at! It’s probably a good thing we moved to England straight after.”

“Yeah,” said Michael. “Going blank is bad! But so is sweating . . .” Touching his forehead, he wiped away a big bead of sweat that had appeared.

“I don’t want to go red,” said Josie, touching her pale, freckly cheeks. “If my face goes red on television, I’ll have to move to another country--like you did, Tom!”

I wished Josie hadn’t reminded me that we were going to be on television too. Standing up onstage and talking in front of the whole school was scary enough, but knowing that lots of people would be filming us too made it feel ten times worse. Now that Ahmet was the Most Famous Refugee Boy in the World, millions of people had found out that we were going to Buckingham Palace for tea with the Queen, and a lot of reporters from the World’s Press wanted to film our assembly for the news. So Mrs. Sanders was letting them--which meant we were probably going to be on every news channel in the country.

Mrs. Khan, who is the best teacher anyone could ever have, said we should try and pretend the reporters weren’t there, and that would make doing the assembly easy. But I don’t know how anyone can pretend something isn’t there when it is. Especially when the something is real people with cameras who are going to be staring at you! It’s always easier for me to imagine things are there when they aren’t--not the other way around. My imagination isn’t strong enough to make real things disappear.

Looking at Michael and Josie, I started to wonder which was worse--going red or going blank or sweating so much it looked like you’d been caught in the rain. I couldn’t decide, so I told my brain to try not to do any of them.

“Did you all practice again at home yesterday?” I asked. “I did and Mum said I was good but that I should stand up straighter.”

Everyone nodded, except Tom.

“I tried,” he explained. “I mean, I wanted to . . . but you know . . . brothers . . .”

Josie gave him a pat on the shoulder. Tom has more older brothers than should be allowed, and they never leave him alone. He has to share a room with two of them, and the main things they like doing are play-fighting and teasing him and stealing his food, which they do all the time. I’ve heard grown-ups tell Tom he’s lucky to be the youngest brother. But I don’t think Tom feels that way at all.

As the bus came to a stop and we got off and made our way toward the school gates, I told myself that everything was going to be fine. After all, Mrs. Sanders had told us exactly what she wanted us to talk about: why the Queen had invited us and what we were going to say to her. And Mrs. Khan had helped us write everything out and had let us stay in at break times all week to practice too. I had copied out our Ten Important Questions in my best handwriting so we could read them clearly. And Ms. Hemsi, Ahmet’s special teacher who could speak Kurdish just like he did, had helped him practice his part of the presentation in English so he could say why it was so special that the real Queen of England wanted to meet him.

There were only two things that could spoil any of it. The first was if one of us forgot to speak when it was our turn. But the second thing was even worse: and that was if Brendan the Bully decided to do something bad to Ahmet in front of the whole school and the World’s Press. I hoped he wouldn’t, but you can never be too sure with bullies. Especially not one who hated Ahmet so much that he nearly got expelled because of it.

2

The Revenge That Stunk

Brendan the Bully hates Ahmet. And me. And Michael. And Tom. And Josie. In fact, I think he might hate everyone, but he hates us the most, because a few weeks ago he got caught calling Ahmet so many horrible names that he nearly got expelled. It wasn’t our fault that happened, but bullies don’t care if things are your fault or not--they just need someone to blame. So Brendan-the-Bully blamed all of us, but he blamed Ahmet the most. That was why I knew I had to keep a close eye on him and make sure he didn’t do anything to ruin the assembly or our trip to see the Queen.

When we got into school, we made our way to the classroom. Ahmet wasn’t there, but as we were sitting down at our tables, he ran in and sat next to Ms. Hemsi, his special teacher, at the back of the class. I gave him a quick wave and he gave me one back.

After that, everything began to feel strange and normal all at the same time. Mrs. Khan started to call roll, just like she always did, but instead of everyone saying “Here, Miss,” in bored voices, they all answered their names in a jumpier way than usual--as if they had ants in their pants that were making them shuffle in their seats and look back at the five of us. I noticed Brendan the Bully and his two best friends, Chris and Liam, looking back too. But instead of scrunching up their faces at us like they usually did, they were laughing and whispering.

Ahmet didn’t seem to notice that everyone was looking at all of us, but Josie’s face was now so red and blotchy that it looked like a pizza, and Michael was sweating so much that even his glasses were steaming up. He also looked as if he was having a competition with Tom to see who could touch his hair the most. Tom kept patting his bright blond spikes every few seconds as if to check they were still there, and Michael kept poking at his bubbly Afro as if wanting to make sure it wasn’t melting. I could feel my ears burning and my heart thumping inside them as I waited for Mrs. Khan to finish the roll.

After what seemed like three years, she finally did, and told me and Ahmet and Tom and Josie and Michael that we could leave early, and that Ms. Hemsi could go with us too. We grabbed our notes and our royal invitations, and Ahmet grabbed his bright red backpack. It still smelled of old baked beans--even though his foster mum had washed the bag with extra-strong liquid detergent at least nine times. That meant every time Ahmet picked up his bag, he had to smell that horrible smell and was forced to remember the time when Brendan the Bully had poured huge cans of baked beans inside it, just to be mean to someone who was a refugee. I guess there are some bad smells and memories that not even liquid detergent can get rid of.

“How are you all feeling?” asked Ms. Hemsi as we hurried down the corridor toward the main hall.

“OK,” said Tom, his voice sounding extra squeaky.

We all nodded in agreement, but I knew we weren’t really OK at all. Only Ahmet looked as if he was actually happy and not pretend-happy. He was holding his invitation out in front of him carefully, as if it was made of glass, and smiling. I wondered if back in his school in Syria, he was used to doing lots of assemblies. Maybe before the war had started and he’d had to run away, he had stood on a stage and spoken to his whole school lots of times. I told my brain to remember to ask him later, or to ask Ms. Hemsi to ask him for me.