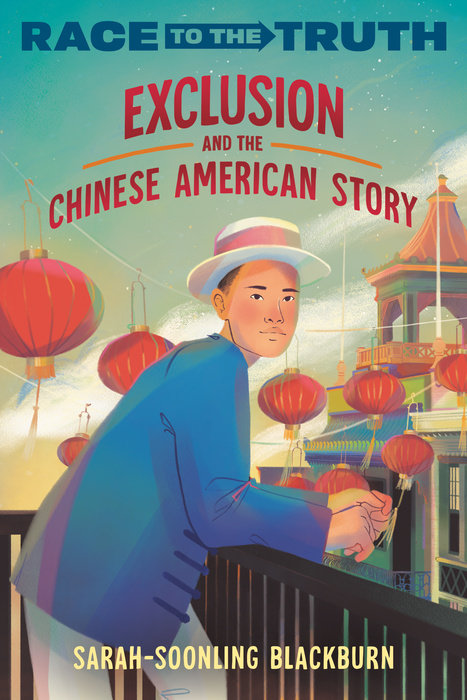

Exclusion and the Chinese American Story

Exclusion and the Chinese American Story is a part of the Race to the Truth collection.

Until now, you've only heard one side of the story, but Chinese American history extends far beyond the railroads. Here's the true story of America, from the Chinese American perspective.

A Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection

If you've learned about the history of Chinese people in America, it was probably about their work on the railroads in the 1800s. But more likely, you may not have learned about it at all. This may make it feel like Chinese immigration is a newer part of this country, but some scholars believe the first immigrant arrived from China 499 CE--one thousand years before Columbus did!

When immigration picked up in the mid-1800s, efforts to ban immigrants from China began swiftly. But hope, strength, and community allowed the Chinese population in America to flourish. From the gold rush and railroads to entrepreneurs, animators, and movie stars, this is the true story of the Chinese American experience.

An Excerpt fromExclusion and the Chinese American Story

Chapter 1

Becoming Chinese American

What would make you leave your home and undertake a long, uncomfortable, and often dangerous journey across the ocean to an unfamiliar land? In the middle of the 1800s, the first major waves of Chinese people started arriving in a place called California. China and California were not only separated by thousands of miles of ocean, they were separated by differences in language, religion, and history. China was an ancient civilization, while the United States was a very young nation. In fact, California only became a state in 1850. Before the 1850s, the few Chinese people in America, like Afong Moy, were often making the much longer journey to the big cities of America’s East Coast. With Californian statehood, however, the United States seemed just a little bit easier to reach than it had before, even though it was still terribly far away. The Chinese people who immigrated to this new country were leaving behind their homes, their families, and everything else that had been familiar to them before. Most left home with the hope that they would one day return, but there was no guarantee that they ever would. Making the decision to leave must have been an emotionally difficult one.

The journey from China to the United States was also physically difficult. It required spending a month or more on a ship crossing the vast Pacific Ocean, and the voyage was uncomfortable. Most Chinese people who set off for America were not wealthy, and they had to borrow money from friends, family, or money lenders to help pay for their passage. Even with borrowed money, these passengers could only afford to travel in steerage, or the lowest class of travel. Traveling in steerage meant sharing sleeping quarters with the other steerage passengers, often including sharing bunk beds covered with thin, straw mattresses. The food on the journey was basic and unappetizing, and the sanitation was awful. Imagine the smells of all the people crammed in together for such a long time with no showers, no modern toilets, and no proper health care. Many people died on the journey. On one ship that made the journey from Hong Kong to San Francisco during that time period, one out of every five people aboard did not survive the voyage.

Now that you can imagine just how difficult the journey to the United States was for early Chinese Americans, ask yourself this question again: What would make you leave your home and undertake a long, uncomfortable, and often dangerous journey across the ocean to an unfamiliar land? The lure of what might await on the other end would have to seem worth the pain of leaving family, the discomfort of the voyage, and the risk of losing your life. The lure that finally pushed more Chinese people to take those risks was one that has lured people across human history--the lure of gold, and the better life that might come with it.

Gold

It was 1848 in what was soon to become the American state of California when a white sawmill worker named James W. Marshall reported finding gold in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The news that a fortune might be hiding in the great mountain range’s soil and streams quickly spread around the world. Thousands of people from across North America and the globe made their way to California, arriving from Europe, Latin America, Asia, and even as far away as Australia.

In the early years of the excitement, Native and Indigenous people from the region participated in the search for gold. Soon, however, many of the new settlers wanted the land for themselves. These settlers, sometimes turning to violence and even murder, forced many Native people to leave their lands. They did not want to share the wealth that might still be discovered, and to some of these settlers a Native person’s life was not as important as the possibility of digging up a fortune. And yet, the competition for gold grew. More and more people from more parts of the world continued to arrive to try their luck. The California Gold Rush had begun.

In China, the craze for gold started like this: Merchants had long traveled between the Americas and China to buy and sell goods, but now these merchants also spread tales of a place where gold could be picked up from the land and where poor people were becoming rich overnight. For people living in Guangdong Province on the coast of southern China, the news of gold was especially alluring. China is a large country, and different regions of China have different histories, languages, and ethnic groups. At the time, Guangdong Province was largely made up of people who spoke Chinese dialects--forms of language that are spoken in a certain region or by a certain group--like Taishanese, Cantonese, Teochew, and Hakka.

In the mid-1800s, Guangdong Province and other nearby areas had gone through years of extreme hardship. Flooding and droughts led to crop failures that led to famine. A war between the British and Chinese known as the Opium War had forced many farmers off their land. The Chinese wanted to end the trade in an addictive drug called opium because it was causing harm to too many people, but the British wanted to continue making money through opium. They wanted to keep the large port cities of the region, like Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong, open to foreign trade. The British ultimately won the Opium War, continuing the traffic of opium through the province and taking the port city of Hong Kong as their own. The challenges of the war had led to high taxes and limited options for the future. All but the richest people were suffering.

When people in Guangdong Province started hearing stories of Gam Saan (or “Gold Mountain”), the hardships they might face trying to get there seemed like nothing in comparison to the hardships they were already facing at home. Then, in 1852, a massive crop failure was the last straw for many people. That year more than twenty thousand Chinese people arrived in San Francisco to seek a better life, about ten times as many as had arrived just the previous year. Almost all of these people were men, setting out to seek their fortune by looking for gold. For the next several years, more and more Chinese people arrived in California to try their luck at finding gold. By 1860 about one quarter of all the gold miners in the region were Chinese.

Like most tales of easy riches, however, the stories about Gold Mountain were much better than the reality. Life for Chinese people in California was not easy. While some lucky miners found a fortune in gold, many more barely scratched out a living. They had borrowed money in China to pay for their voyage to California. On top of what it cost to live, the miners had to earn enough to pay back what they had borrowed, plus interest, a fee for borrowing money that has to be repaid to the lender. Whatever gold was left over did not stay in their pockets either, as many miners felt a responsibility to send as much as possible home to their families in China.

A day in the life of the typical Gold Rush miner was brutal. They woke up at dawn and spent twelve to sixteen hours a day doing the backbreaking work of digging and washing dirt in the hopes of a glimmer of gold. American and European miners had realized that the numbers of Chinese miners would only continue to grow, and many started to speak out with hatred. They wanted to limit the chances that one of the large gold discoveries would go to the Chinese. Out in the gold fields, each miner had their own section called a claim. If a Chinese miner got lucky by finding gold and did not carefully guard his claim, it would be stolen by someone else. Sometimes Chinese miners had to work for white miners for only a small cut of any profits they might find. More often, Chinese miners had no choice but to work on claims that had already been searched through and abandoned. That meant that the Chinese miners’ chances of finding gold were even lower than everyone else’s. Most never found anything of much worth.

At the end of the long day of work, miners returned to their camps. Chinese miners tended to live together for protection and for a feeling of familiarity. They were far away from home, in a land with what seemed like strange food and customs. Most Chinese miners didn’t speak English. It isn’t hard to imagine how homesick they must have felt. By living in camps together, the Chinese miners were able to cook familiar foods, speak their native languages, and swap stories about their families with people who would understand.

The Chinese miners created a community with one another. The miners who were fortunate enough to find gold started new businesses. They had learned through hard, personal experiences that the United States was not always a friendly place for Chinese people, and they wanted to make the experience a little bit easier for the newest Chinese arrivals. Others had come from wealthier backgrounds in China, making the voyage across the Pacific not in steerage but in their own cabins. These more successful Chinese people formed mutual-aid groups known as associations to support the growing Chinese community. You will hear about the associations many more times throughout this book. People from the associations would meet hopeful new miners right as they got off the boats from China. The associations would help these newcomers find somewhere to stay, get what they needed to work in the mines, or find other jobs. The growing Chinese community started to put down roots in the United States, building temples and schools as well as stores and restaurants. Some of these buildings still exist today.

Yee Ah Tye, A Powerful Man

In 1852, a man arrived in San Francisco from Guangdong Province. His name was Yee Ah Tye, and he was about twenty years old. Traditionally, Chinese people list their last name first, so his last name was Yee and his first name was Ah Tye. You will see many other names throughout this book that follow the same pattern. Ah Tye spent his first night on American land shivering in the doorway of a building with some of the other new arrivals. But Yee Ah Tye had some different experiences that set him apart from most of his companions. For one thing, he had lived in Hong Kong, and because Hong Kong was controlled by the British, Ah Tye could speak English. Ah Tye worked as a translator, and he quickly rose in one of the most powerful associations, the Sze Yup Association. Yee Ah Tye was known for being an outgoing leader who would make deals with the white authorities in California, helping to ease the transition for new Chinese arrivals. But Ah Tye also had a dark side to his reputation. A newspaper called the San Francisco Herald ran an article describing how he would brutally punish any Chinese arrivals who did not do what he said. He was also taken to court by a Chinese woman who claimed that he was trying to extort money from her, or forcing her to give him money by using threats or other illegal methods.

Perhaps to escape his conflicts in San Francisco, Yee Ah Tye eventually moved to Sacramento, California. Newspaper reports from his time there show how he became one of the most prosperous Chinese people in the state. In 1861 he hosted a Lunar New Year dinner for other wealthy Chinese people as well as for important leaders from the white community, like a judge, a doctor, and a lawyer. There were twenty-six courses served for dinner, including birds’ nest soup, two kinds of duck, five brands of champagne, and cigars to finish the meal. This kind of feast was out of reach for most Chinese people at the time, but powerful association leaders often ate well. Archaeologists have looked at the sites where association boardinghouses used to stand, and they have found the remains of expensive Chinese fish, multiple species of birds, and a whole lot of pork. Eating pork symbolizes wealth and prosperity to Chinese people, but it was very expensive in California at the time. By looking at what these associations left behind, archaeologists have been able to prove that powerful association leaders like Yee Ah Tye lived a very good life compared to the other early Chinese Americans.

At the end of his life, Yee Ah Tye continued to go against tradition. He had spent most of his life in California, and he decided that he wanted to be buried in the United States. Most Chinese people came to the U.S. to find their fortune and return home to China, not to settle down permanently in their new country. If a Chinese person died in the U.S., most thought it was important that their remains be sent back to China so that their spirit could be in the land of their ancestors. Ah Tye surprised his family by requesting to be buried in this new country, though he incorporated Chinese traditions into his funeral. Chinese people often give offerings of food at funerals or at the burial sites of relatives. In typical fashion, Yee Ah Tye’s spirit was sent off with a feast of meat, cakes, fruits, wine, and more.

Yee Ah Tye’s choice to be buried in his new country shows how some Chinese people in America were starting to think of themselves as a new sort of person, a Chinese American person. These early Chinese Americans felt a strong connection to their new home, even though this new home didn’t always act like it wanted them. During the Gold Rush, white Americans raised concerns about all the foreigners whom they saw as competition, especially miners from Latin America and China. In response, California created taxes that only foreign miners were required to pay. One of these racist taxes, the Foreign Miners’ Tax Act of 1850, required that all miners who were not U.S. citizens pay twenty dollars a month to the state of California. White European miners from countries like France, Germany, and Ireland were not required to pay this tax, even though they were also technically “foreigners.” Many Latin American miners, unable or unwilling to pay the tax, returned to their home countries. Many Chinese American miners left the mines as well, but they had traveled over a wide ocean and often could not afford to make the journey back to China. Instead, many Chinese people were pushed into cities like Sacramento and San Francisco, where they created the country’s first Chinatowns.

In spite of the hardships, the promise of a fortune in gold remained strong, and throughout the 1850s more Chinese people continued to make their way to California in hopes of striking it rich. The Foreign Miners’ Tax Act of 1850 was overturned after less than a year, and thousands of Chinese people returned to the gold mines. The reprieve didn’t last for long. Remember that in 1852 ten times as many Chinese people came to the U.S. as came in 1851. If American miners were upset about competition from Chinese miners before, they were even more upset now. The Foreign Miners’ License Act of 1852 was passed, and this time Chinese miners were the clear and only target. This new law required that Chinese miners pay about three dollars per month to the state of California--not as much as the twenty dollars required before, but still a lot of money for people with very little to begin with, whose only hope of making it rich lay in finding a big chunk of gold in the dirt and mud of the mines. It’s no wonder that most miners never became rich. As mining became less and less appealing, Gold Mountain was no longer the only destination for immigrants from China. Instead, Chinatowns in cities like Sacramento and San Francisco continued to grow, and these became the true center of life for early Chinese Americans.