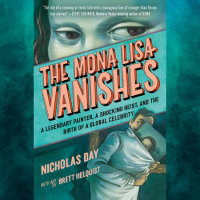

The Mona Lisa Vanishes

“The tale of a stunning art heist with a contagious love of stranger-than-fiction true stories!”—Steve Sheinkin, Newbery Honor–winning author of Bomb

The true story of how Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece became the most famous painting in the world after being stolen from the Louvre, written as a “witty thriller” (The New York Times) and featuring black-and-white illustrations throughout.

SIBERT MEDAL WINNER • BOSTON GLOBE—HORN BOOK AWARD WINNER • ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: Publishers Weekly, School Library Journal, Booklist, Kirkus Reviews, NPR, The New York Public Library, The Chicago Public Library, The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

On a hot August day in Paris, just over a century ago, a desperate guard burst into the office of the director of the Louvre and shouted, La Joconde, c’est partie! The Mona Lisa, she’s gone!

No one knew who was behind the heist. Was it an international gang of thieves? Was it an art-hungry American millionaire? Was it the young Spanish painter Pablo Picasso, who was about to remake the very art of painting?

Travel back to an extraordinary period of revolutionary change: turn-of-the-century Paris. Walk its backstreets. Meet the infamous thieves—and detectives—of the era. And then slip back further in time and follow Leonardo da Vinci, painter of the Mona Lisa, through his dazzling, wondrously weird life. Discover the secret at the heart of the Mona Lisa—the most famous painting in the world should never have existed at all.

An Excerpt fromThe Mona Lisa Vanishes

The Creation of the Mona Lisa

Imagine a palazzo--a magnificent Renaissance building.

It’s Florence, 1503. There are a lot of palazzos around. Choose a good one.

Now imagine a man: handsome, charming, gentle. Make him a painter.

Imagine a woman: intriguing, unknown, beautiful. Make her a model.

Do you see them?

Neither of them should be there.

The man shouldn’t be a painter at all. Born into a long line of notaries--an early version of a lawyer--the man should have gone into the family business. Being a notary may have been the most boring profession in Renaissance Italy, but it was steady.

Instead, he designed flying machines. He dissected dead bodies. He inflated pig bladders and launched them around the room. He was an extraordinary, ingenious, wondrously weird man.

He was Leonardo da Vinci. He painted a little too.

But he didn’t have a reason to paint this portrait of an ordinary Florentine woman.

The woman shouldn’t be posing for him. She shouldn’t be in a room with any man. She should be hidden away in a convent, the home of a Catholic religious order.

Her family hadn’t had enough money for a dowry, the sum any girl in Florence needed for a marriage, and girls without dowries disappeared into convents, cut off from the world. But a marriage was arranged, somehow, and she prospered. There were children, and there was money--enough money to commission a painting.

Thanks to that painting, she became the most recognizable face in the world.

We don’t know how long she sat for Leonardo. We don’t know if they ever saw each other again.

We do know that afterward, the woman staring out of the painting--Lisa Gherardini--will watch as the city around her is invaded and pillaged. It will be brutal. Upon her husband’s death, she will finally enter a convent.

We know that the man staring into the painting--Leonardo da Vinci--will flee Florence. He’ll move up and down Italy, a brilliant artist without a place to call his own. As an old man, he will end up in another country altogether. When he makes the journey over the Alps to France, he will strap this portrait, the Mona Lisa, to a donkey.

He will die.

But what happens in that palazzo will make her ageless. She will live through the centuries.

She will become immortal. She cannot die.

She can, however, be kidnapped.

The Theft of the Mona Lisa

It was Monday, August 21, 1911, and it was morning, finally. From his hiding place inside the closet, the man could hear the footsteps of the Louvre guards.

In the empty, enormous rooms of the Louvre, the footsteps must have echoed.

They came closer, and closer still, and then--farther. Each time, the guards walked right past him. He had no idea if they were looking for him. But they should have been. On Sunday, the man had come to the Louvre just like any other visitor, but when the museum was closing, he didn’t do what the other visitors did.

He didn’t leave.

The Louvre wasn’t a hotel. You weren’t supposed to spend the night. But a few months before, a French journalist had done the same thing. The journalist didn’t think the Louvre’s security was any good, and to prove it, when the museum closed, he crawled inside the sarcophagus of an Egyptian king and stayed there until the morning.

He was right about the security. No one bothered him. Not even the Egyptian king whose sarcophagus he’d borrowed.

All the journalist took from the Louvre was material for an article, an expose on the museum’s lousy security.

This man wanted to take more than that.

They’d both gone unnoticed because the Louvre wasn’t just an art museum. It was a labyrinth, with a thousand years of hiding places.

It was first built as a medieval fortress, complete with a moat. It became a palace, the magnificent home of French royalty. With every monarch, the palace grew yet more palatial, sprouting vast wings and pavilions like some sort of fantastical beast. After the French Revolution, which overthrew the monarchy, it completed its final transformation into a museum, a monument for the new French Republic.

By then, it sprawled. It occupied the space of nearly forty football fields. It was as long as the Eiffel Tower if the Eiffel Tower were laid down on the ground and lined up end to end with another Eiffel Tower. It was a seemingly endless expanse of grand rooms, like a mirror reflected in a mirror.

Alongside those rooms were centuries of nooks and crannies. These were less grand: storerooms, cupboards, annexes, cubbyholes. A human being could squeeze in almost anywhere. A century ago, no one at the Louvre even knew how many of these hideaways there were. There were too many to count.

And on Monday, August 21, 1911, no one at the Louvre knew that someone was hidden away inside one of them.

This man had rejected the sarcophagus in favor of a storage closet. The Louvre was also a sort of art studio, where amateurs came to copy the paintings of the greats. The museum let these copyists--that was the term for them--store their things there.

When the Louvre closed on Sunday, the man slipped in among the easels and paint boxes.

That was the easy part. What came next was harder.

The man waited behind the closet door. He listened to the footsteps.

Let us leave him there for a minute.

He’s completely still, but outside the museum, a new century is accelerating. Everything is in motion.

The changes have been blindingly fast. New inventions like automobiles and airplanes are a blur on the street and in the sky. Their speed is altering fundamental facts of life--things as basic as time and space. People can move across the globe at unimagined velocity, connecting places that were once isolated. Information follows at the same breathtaking pace. All of this is shrinking the world. A local story--the story of a criminal at loose in the Louvre, for example--can now become a global sensation.

All of this will shape what happens when the closet door opens.

It will be a story at the mercy of this new breakneck century.

The halls of the Louvre went quiet.

A closet door cracked.

When the man stepped out of the storage closet--sleepless from a night with the easels, sweaty in the August heat--he was alone.

Or almost alone. He was surrounded by the most extraordinary paintings in the world.

The storage closet had an extremely good location--a suspiciously good location. Around the corner was the Salon Carre, the home of the most prized paintings in the Louvre. The great Italian painters were all represented: Raphael, Titian, Tintoretto. And Leonardo da Vinci.

The museum was closed on Mondays, but it wasn’t abandoned. The staff still came in: curators, cleaners, maintenance workers. There were guards too, but fewer, and they had to cover an area the size of a small city.

None of them saw the man leave the closet. But if any had, they might not have noticed. He was wearing a white smock, the uniform of the Louvre maintenance workers. It was a suit of invisibility. He was too normal to be noticed.

He didn’t look like a thief.

He walked around the corner into the Salon Carre, the heart of the Louvre. It was all his for the taking.

The paintings in the Louvre were not locked down. This lack of security was actually a form of security: in case of fire, the guards were supposed to grab the paintings and run. Still, some paintings--especially valuable paintings--were hung in a way that required inside knowledge. They had to be removed from their hooks in a very precise way, a way that anyone who didn’t already know was unlikely to figure out fast.

The painting the man wanted was hung that way.

Luckily, he didn’t have to figure it out. He already knew. He slid it off the hooks in seconds.

It was all going according to plan.

On the wall, the painting was sublime. Off the wall, it was agony. Painted not on canvas but on wood, surrounded by an antique frame and glass, the whole thing weighed in at almost two hundred pounds.

Somehow, the man wrestled it into the nearest stairwell. Here, he was safe--or safer. He removed the glass case and cut away the frame. The painting itself was all that was left: three slabs of wood joined together, measuring less than three feet high and two feet wide.

It was over four hundred years old. And it was his.

Almost.

There was a problem. A painting on canvas, once outside of its frame, can be rolled up. A painting on wood can never be rolled up. A slab of wood is always the size of the slab of wood.

There was no good solution. So he went with a bad solution: he put the painting--fragile, irreplaceable, unprotected--under his sweaty white smock.

He started down the stairwell, and when he reached the bottom, he opened the door--or he tried to open the door. The door was locked. He put its key in the lock and opened the door--or he tried to open the door. The key didn’t work.

Suddenly, it was not all going according to plan.

The man removed the doorknob with a screwdriver. But removing a doorknob doesn’t open a locked door--the door is still locked--and before he could do anything else, he heard footsteps. Someone, possibly a guard--probably a guard--was coming down the stairs.

He was trapped. He was cornered at the bottom of a stairwell, sweaty and sleepless, with a priceless painting poorly hidden under his smock. It wasn’t a good look.

The footsteps came closer, and closer, and then . . .

It wasn’t a guard. It was a plumber. The Louvre was so large it had its own plumbers.

The plumber saw a man at the bottom of the stairwell. Who did he see? What did he see? Did he see the sweat? Did he see the desperation? Did he see the shape of a painting?

The man at the bottom spoke first. He didn’t make excuses. He didn’t explain what he was doing there. He acted like he belonged. Look at this door, he said to the plumber. It doesn’t even have a doorknob! How am I supposed to get out of here?

The plumber saw the white smock. He saw someone too normal to be noticed. With his pliers, the plumber twisted the inner workings of the lock. It sprang open, and the man sprang out of the trap. He walked out of the stairwell, into a courtyard, through a gallery, and toward the Louvre’s entrance.

There was a guard at the entrance--or there was supposed to be a guard at the entrance. But at this minute, on this Monday morning, the guard was gone. He was fetching a bucket of water.

He’d picked the worst time in the long history of the Louvre to clean his booth.

The man in the white smock--sweaty, sleepless, triumphant--walked out of the Louvre and into Paris.

Then he disappeared.

He’d stolen two things from the Louvre.

The first was a doorknob.

No one would care about the doorknob.

The second was the Mona Lisa.

A lot of people would care a lot about the Mona Lisa.

The Ludicrous Fame of the Mona Lisa

The theft of the Mona Lisa was the greatest heist in art history. Every heist that followed--every stolen painting--was an imitation.

Not an imitation of the strategy, or the craft, or the luck, but an imitation of the sheer bravado: the idea of stealing something that couldn’t possibly be stolen.

A year before the theft, in a spooky coincidence, the director of the Louvre had been asked about the possibility: Could the Mona Lisa be stolen? The director had laughed. He’d said the Mona Lisa would be no easier to steal than the massive towers of Notre-Dame, the medieval French cathedral.

It was a question that didn’t interest many people. Before the Mona Lisa was stolen, most people had never heard of it. Outside of select circles--artists, art lovers, people lost in the Louvre--the painting hardly existed. It was just another work by Leonardo da Vinci. A strange, small, dark portrait.

After it was stolen, it became a sensation.

For the Mona Lisa, being stolen was a very good career move.

Today, the painting is so famous that stealing it sounds like a joke. It sounds like stealing the Washington Monument or Niagara Falls; it sounds absurd. The Mona Lisa is so popular today it can hardly be seen: a visitor to the Louvre is lucky to get close enough to catch a glimpse, to confirm that it exists. But that’s enough, because every visitor to the Louvre already knows what the Mona Lisa is supposed to look like.

The reason they know is because of what happened on August 21, 1911.

Before that date, it was possible to see the Mona Lisa without already knowing what the Mona Lisa looks like.

Afterward, it was not.

This is a story about how a strange, small portrait became the most famous painting in history. It’s about a shocking theft and a bizarre recovery. It’s a glimpse of a new age--a future of conspiracy theories and instant celebrity.

But it is also the story of another way of looking at the world--clearly, plainly, without assumptions or expectations. It’s the story of how Leonardo da Vinci looked at the world.

To solve the theft of Leonardo’s painting, the world needed someone like Leonardo da Vinci himself: someone who observes.

The world would not get Leonardo.

Like the Mona Lisa that August in Paris, Leonardo was long gone.

She’s Gone

In Which No One Notices That the Mona Lisa Is Missing, and Then Everyone Everywhere Notices

Monday Morning

For a moment--just a moment--put the man in the white smock back in his closet.

Make him sleepless and sweaty again. Make him not yet triumphant.

Bring back the footsteps.

The footsteps were from a crew of workmen--the men who were supposed to be in white smocks. They walked toward the Salon Carre, where the head of the crew--the head of all maintenance at the Louvre--stopped his men. “This,” he said, pointing to the Mona Lisa, “is the most valuable painting in the world.” He used the French name for the painting: La Joconde.

The crew looked at the Mona Lisa. They had no idea that they were the last people who would see it in the Louvre for a very long time.

After they left, the man came out of the closet. He went into the Salon Carre; he went out of the Salon Carre; he went down a stairwell.