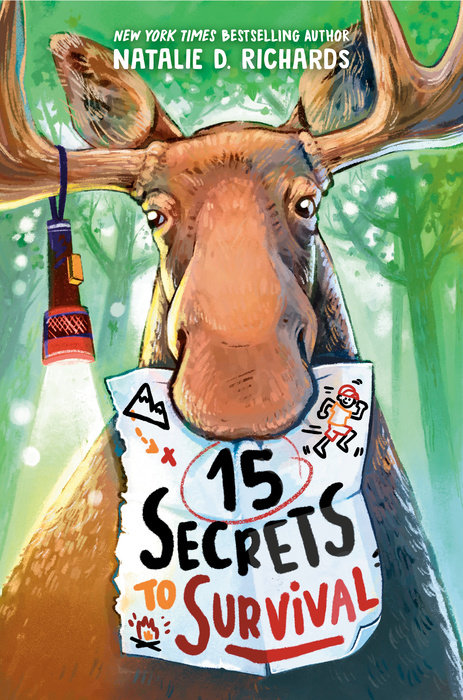

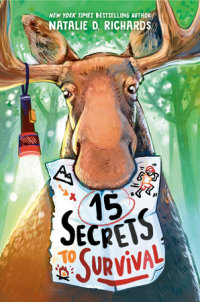

15 Secrets to Survival

New York Times bestselling author Natalie D. Richards's middle grade debut about a group of four classmates forced to navigate the wilderness for an extra credit project with nothing but the pages of a survival handbook—and each other—to save them.

When classmates Baxter, Abigail, Turner and Emerson break a school rule, they’re forced to travel to the middle of nowhere for an extra credit project. They think things can’t get much worse. After all, how will learning to survive in the wilderness help them stay out of trouble in school?

What starts off as a weekend of team building takes a scary turn when their instructor goes missing and they are given nothing but pages of a survival guide to complete a series of challenges.

They soon learn the woods around them have unexpected surprises. Will they discover a way to work together to find their teacher and overcome the dangers of winter in the mountains?

A recommended choice for classroom discussions on earth science and educators looking for survival books for kids.

An Excerpt from15 Secrets to Survival

Chapter 1

December 16, 3:25 p.m.--Montana

Our car grinds to a halt at the head of a narrow gravel drive. I look up from the back seat, seeing nothing but trees and mountains in every direction. I slouch lower and feel my throat go tight.

Is this really a fitting punishment? I mean, I already lost my spot on our school’s e-sports team thanks to my active school discipline status. And it was just a few text messages.

Okay, fine, a few text messages and a Know and Grow team disqualification. For the record, they shouldn’t have disqualified us, because we weren’t cheating. We were just sharing our feelings with one another. And by feelings, I mean our dislike for one another. And by dislike, I mean loathing, but I already tried explaining that back when it all happened. That’s when a funny little line showed up between Dad’s eyebrows and Mom put her hand on her chest like she was trying not to cry and I decided that it was probably not a good idea to bring up the fact that it’s kind of Mom’s fault. She’s the one who was all, “You four will make a great team for this class, Baxter.”

Usually our elective courses at Lincoln are kind of awesome. Last year I took a class with three of my friends in a team to build and compete with derby robots. I figured a team trivia competition couldn’t be that bad, even with Emerson, Turner, and Abigail. Didn’t quite have that one right, did I?

Anyway, the day after Mom and Dad met with our teacher, they informed me that I would not be going on the tropical holiday cruise with them over winter break as planned. Instead the other Team Starbright members and I would be going for a weekend of responsibility and teamwork in the remote mountains of Montana with Mom’s uncle Hornsby. And somehow, while doing all that, we’re supposed to think of a group project we can do for replacement credit.

Dad steers around yet another curve. We’ve been weaving through mountains and forests for eight bazillion hours. How are we still in the middle of nowhere? Where are all the cities? Heck, for that matter, where are all the houses? Or farms? I think I’d get excited if I spotted a random barn on the side of the road at this point.

“Doobledee. Cookie.” My baby sister, Vivi, offers this conversation starter from her car seat beside me.

“It sure is beautiful,” Dad says with a low whistle. “I almost wish I could stay with you.”

I doubt it. Dad and the other parents are going to Aruba while we’re here, which is so unfair. But I make a strangled noise that might sound like agreement.

“You may thank me for this, Baxter,” Mom says, her pink nails tap-tap-tapping at her throat while she beams at the snowy pine trees. “It’s an amazing opportunity.”

I squirm in my seat, because this does not feel like an opportunity. A missing-child-in-the-mountains news report, maybe. I know Uncle Hornsby managed summer camps, but is this really the right environment for a school project?

“Coo-kie.” This time Vivi enunciates each syllable clearly, tapping her chubby toddler knee with her pointer finger, just in case Mom wasn’t sure where said cookie should be deposited.

“Just a minute, Peanut,” Mom tells her, grabbing for the diaper bag.

Dad whistles his little up-down tune and shakes his curly hair. “Beautiful!” he says again.

I slouch even lower, until I can barely see over the side of the door and out the window. Not like there’s much to see anyway. Like someone coded an infinite loop of trees, snow, and mountains.

Mom fishes a couple of animal crackers out of a plastic container and hands them to Vivi. Crumbs stick to her pink nails, and she looks at me, her matching pink lips smiling.

“Oh, Pumpkin, I just want the four of you to remember how much history you share. Remember in the third grade when you all went to the state fair? You were precious.”

I give a weak laugh, because I definitely do remember it, but I’m sure Mom has the whole thing remembered in Mom Mode. That’s the weird moms-only version of memory where everything past tense turns into a soft-focus video with a fairy-tale ending. If you ask my mom about the fair, she’ll talk about sticks of cotton candy and all four of us giggling on the Hula Bula in one car. But her version of this event magically omits Abigail losing her headband (and her mind, briefly, as a result) and Emerson throwing up on me and Turner.

Mom has especially Mom Mode memories about everything involving the Getalong Gang. That’s what she calls us. She loves to point out that she was the one who came up with this moniker first, and everyone had better remember it. As if any of us would try to take credit? Anyway, I think that’s why she was so upset about the Know and Grow disqualification incident. I think that until she read the transcript, she completely believed we liked each other. The truth is, we are the Don’t Getalong Gang.

When you’re really little, you don’t choose your friends. Heck, you don’t even choose your clothes or what you eat for lunch. You wear stupid shirts with frogs on them, eat weird, mushy organic vegetables, and hang out with your parents’ friends’ kids.

For me those kids were always Abigail, and Emerson and Turner. Mom and Dad started a business with Dr. Walters years before Abigail or I came along. And Mr. and Mrs. Casella joined in right after they had the twins. They bought houses in the same neighborhood. We all four went to the same daycare and then preschool, and our parents were sure we would be the best friends ever, just like them. None of us were consulted on the matter. And since I never felt like I had much choice about Mom’s suggestion, we weren’t really consulted on entering the Know and Grow elective class as a team, either.

Dad pulls to a stop at a four-way intersection and looks back and forth. And back and forth.

“Uh, Dad,” I start. “Are we lost?”

Dad shakes his head at his phone and gives a sad, low whistle. “This phone is maybe not working at a hundred percent right now.”

“Reception is probably terrible out here, pumpkin,” Mom says. “Oh! I have directions.”

She digs out a neatly folded letter with scary black printed directions. That’s the note Uncle Hornsby sent, and it’s all we’ve got to go on, because apparently we’re beyond the reach of GPS or any other modern device. My palms feel sweaty at the idea.

“So where exactly is this cabin?” I ask. It looks like we’re driving deeper into the armpit-of-the-middle-of-nowhere.

“Deep in the Montana mountains!” Dad says. “If we were any farther north, we’d be in Canada. Just look at this snow.” He whistles appreciatively and maybe I should press my hand to my chest like Mom, because I feel a little bit like crying too.

“We’ll be there in fifteen minutes,” Mom corrects. “Uncle Hornsby said it’s fifteen minutes down the gravel road. Baxter, maybe you should time it. Get started on some of those responsibility skills.”

“Well, if Uncle Hornsby says so,” I say, reaching for my pocket. And then I remember: No phone to use for a stopwatch. No phone or tablet or gaming device of any sort whatsoever. Mom hands me a watch from the Dark Ages, and I have no idea what to do with it, so I just start counting in my head and hoping I won’t lose track.

“Uncle Hornsby knows so much about these mountains,” Mom says. “He led the camp here for almost twenty years, and he taught lots of kids how to work together and how to be responsible. This is a great opportunity for you, Baxter.”

Ms. Westwood thought it was a great opportunity for the four of us to tackle teamwork again too, but I don’t get it. What does wandering around the wilderness have to do with a team trivia class? Maybe Uncle Hornsby has a Fountain of Opportunity out here somewhere.

Great-uncle, actually. I’ve never even met him, but Mom went to his camp every summer, starting when she was very small. Sometime when she was in college, the camp shut down. Mom blames cell phones and video games, but she likes to blame cell phones and video games for lots of things. I think the kids just got smart. Who would want to spend two whole weeks of summer break getting bug bites and blisters from hiking boots while walking a zillion miles a day in the mountains? But whatever it was, after it closed, Uncle Hornsby moved on to some half-finished cabin off the grid. Like, way, way, way off the grid.

“How much time is left, buddy?” Dad asks.

Oh, crap. I stare at the watch, hoping it will whisper the answer to me. “Um . . .”

We rumble over an old bridge that rattles my teeth. I see a river burbling underneath us.

“More cookie,” Vivi says.

A sign in her room back home says VIVI IS MADE OF SUGAR AND SPICE AND EVERYTHING NICE. I guess they don’t make signs that say MADE OF CRUMBS AND DROOL AND BABY DOO-DOO.

“Oh, it’s lovely,” Mom says, tapping her pink nails together again.

“All that snow!” Dad says with a happy three-note whistle. “It’s going to be the perfect weather for wilderness training.”

“Don’t people die in the cold and snow?” I ask, because I feel like Dad should consider it. Also, I’m pretty sure no one ever died from sending or receiving unfriendly messages on a group chat.

“Oh, no one will die, Pumpkin.”

“Cookie!” Vivi’s finger stabs into the air again. “Doobledee dee dee!”

Mom hands her another cookie while more trees and snow and yuck fly past my window. I sigh and Mom pats my hand.

“It might be better than you think, you know,” she says.

Three days with three of my least favorite people while my real friends back home will all be celebrating their initiation into the Game Brigade by raiding the GrobGoblin Fortress in Forever Life. Four thousand experience points each and a full set of Invisibility Armor for the team to split. I was supposed to get the gloves, which is all I need for a complete set. Now I’ll be gloveless forever. And in real life I might get buried under a snowdrift or eaten by a yeti.

If it’s the yeti, Abigail, Emerson, and Turner will probably offer him a napkin when he’s done polishing me off.

Our tires bump, bump, bump over the crunchy ruts and dips in the snow-covered road, and then we zip down a hill. My stomach tumbles end over end.

“More!” Vivi says. “More whee!” She shakes her tiny fist. Some days I really worry about that kid. I think she has dreams of ruling a small country.

Six million years and a couple of scary, creaky bridges later, Dad turns left and puts our Subaru into a low gear to descend the ridiculously steep and long driveway curving down to the left. We slide three times, but finally he finishes the corner and I see the edge of a squarish pile of logs and sticks.

Wait. Is that pile of logs and sticks Uncle Hornsby’s cabin? I stare until my eyes hurt, but it doesn’t change anything. This is definitely his cabin. I have seen some rustic places, but this is a whole new level. Some of the logs making the walls still have bark and twigs attached. There are windows, sure, but they’re all a little crooked--like whoever built the place didn’t have a level and instead just eyeballed everything.

Leaning against the door is a long axe, which tells me firewood is going to be a thing this weekend. Chopping it. Hauling it. Burning fires that don’t heat the cabin enough but make us all reek like a campout. Dad had a thing for rustic cabin weekends for a while, so I know about firewood.

Mom opens the door, and three things happen all at once: Dad gives an alarmed whistle. Mom gasps. And a gigantic moose appears through the windshield.

Chapter 2

The moose is standing at the back of Dr. Walters’s open car trunk, and I see striped pink pajama pants hanging off one side of its enormous antlers. Dad turns off the engine and cracks the door, and Mom’s hands go up, pink nails flashing.

“Allen, be careful!”

“That moose isn’t interested in me,” he says. “He’s trying to find something to eat.”

“Like what?” I ask, feeling very alarmed. “What does he eat?”

“I think he’s an omnivore,” Dad says.

“No, moose are herbivores,” Mom says.

“What does that mean?” I ask, and my voice goes all high and shrieky as I try to remember. Carnivores are meat eaters. I remember that part from my dinosaur phase. And one of them is both, but is that the herbivore or the omnivore?

“Herbivore is plants?” I ask, remembering the herb part of the word. Like herbs and spices, which all come from plants.

“That’s right,” Mom says. She’s using the singsong educational voice, and I really don’t think this is the time, because that moose outside is shaking its giant antlers pretty violently.

Dad tweets out a two-tone melody that’s the whistle equivalent of “Uh-Oh.”

“Doobledee,” Vivi says.

“That’s a moose, Peanut,” Mom says softly, still deep into educational mode despite the fear making her voice shaky. “Do you see his big antlers?”

“An-turds,” Vivi says.

“Antlers,” Mom corrects, and then she grabs my dad’s arm. “Oh, is that the twins?”

I see them on the porch, side by side. Mrs. Casella is behind them, her eyes wide behind her gold-rimmed glasses. Clearly she’s seen the moose, because her mouth is open in an O and she has one arm around each kid, as if she’s afraid they’ll bolt off the porch and maybe try to ride the moose.

I don’t think she needs to worry. Emerson is frozen in place, and since she won’t ride anything at the fair that goes faster than the merry-go-round, I don’t think she’s likely to take even half a step closer to that moose. And unless the moose is hiding a deluxe train set under the pajama pants on his antler, I doubt Turner is interested in getting closer, either.

The moose pokes its entire head back inside the open hatchback of Dr. Walters’s car. A tote bag is toppled over--which must explain his headwear--and its contents are spilled out onto the driveway. His antlers bump the edges of the open hatch, and he makes a scary snuffling-grunting sound into one of two grocery bags. Emerson stares from the porch, the tips of her blue hair shivering just beneath her pointy chin.