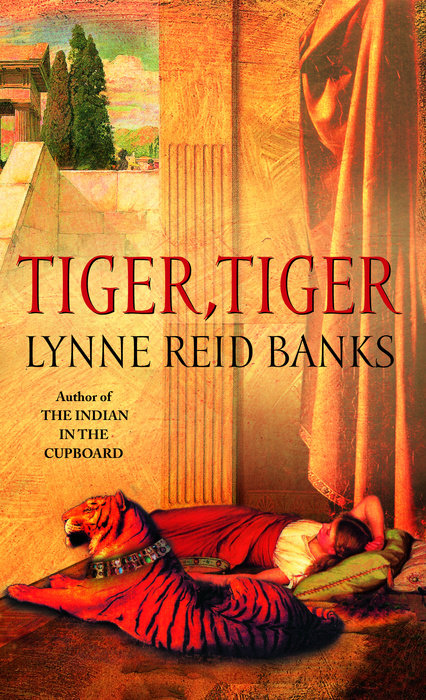

Tiger, Tiger

Two tiger cub brothers are town from the jungle and taken to Rome. The stronger cub is trained as a killer at the Coliseum. Emperor Caesar makes a gift of the smaller cub to his beautiful daughter, Aurelia. She adores her cub, Boots, and Julius, a young animal keeper, teaches her how to earn the tiger's trust. Boots is pampered while his brother, known as Brute, lives in a cold and dark cage, let out only to kill. Caesar trusts Julius to watch Aurelia and her prized pet. But when a prank backfires, Boots temporarily escapes and Julius must pay with his life. Thousands watch as Julius is sent unarmed into the arena to face the killer Brute.

An Excerpt fromTiger, Tiger

ONE

In the Hold

The two cubs huddled together, their front paws intertwined, their heads and flanks pressed to each other.

Darkness crushed them, and bad smells, and motion. And fear.

The darkness was total. It was not what they were used to. In the jungle there is always light for a tiger's eyes. It filters down through the thickest leaves from a generous sky that is never completely dark. It reflects off pools and glossy leaves and the eyes of other creatures. Darkness in the jungle is a reassurance. It says it's time to come out of the lair, to play, to eat, to learn the night. It's a safe darkness, a familiar, right darkness. This darkness was all wrong.

The smells were bad because there was no way to bury their scat. And there was the smell of other animals, and their fear. And there was a strange smell they didn't recognize, a salt smell like blood. But it wasn't blood.

It was bad being enclosed. All the smells that should have dissipated on the wind were held in, close. Cloying the sensitive nostrils. Choking the breath. Confusing and deceiving, so that the real smells, the smells that mattered, couldn't be found, however often the cubs put up their heads and reached for them, sniffing in the foul darkness.

The motion was the worst. The ground under them was not safe and solid. It pitched and rocked. Sometimes it leaned so far that they slid helplessly until they came up against something like hard, cold, thin trees. These were too close together to let the cubs squeeze between them. Next moment the ground tipped the other way. The cubs slid though the stinking straw till they fell against the cold trees on the other side. When the unnatural motion grew really strong, the whole enclosure they were in slid and crashed against other hard things, frightening the cubs so that they snarled and panted and clawed at the hard nonearth under their pads, trying in vain to steady themselves.

They would put back their heads and howl, and try to bite the cold thin things that stopped them being free. Then their slaver sometimes had blood in it.

When the awful pitching and rolling stopped and they could once again huddle up close, their hearts stopped racing, and they could lick each other's faces for reassurance.

They were missing their mother--their Big One. They waited for her return--she had always come back before. But she was gone forever. No more warm coat, no rough, comforting, cleansing tongue. No more good food, no big body to clamber on, no tail to chase, pretending it was prey. No more lessons. No more love and safety.

All their natural behavior was held in abeyance. They no longer romped and played. There was no space and they had no spirit for it. Mostly they lay together and smelled each other's good smell through all the bad smells.

As days and nights passed in this terrifying, sickening fashion, they forgot their mother, because only Now mattered for them. Now's bewilderment, fear, helplessness, and disgust.

There was only one good time in all the long hours. They came to look forward to it, to know when it was coming.

They began to recognize when the undifferentiated thudding overhead, where the sky ought to be, presaged the opening of a piece of that dead sky, and the descent from this hole of the two-legged male animals that brought them food. Then they would jump to their feet and mewl and snarl with excitement and eagerness. They would stretch their big paws through the narrow space between the cold trees and, when the food came near, try to hook it with their claws and draw it close more quickly. The food, raw meat on a long, flat piece of wood, would be shoved through a slot down near the ground, the meat--never quite enough to fill their stomachs--scraped off, and the wood withdrawn. Water came in a bowl through the same slot. They often fought over it and spilled it. They were nearly always thirsty.

The male two-legs made indecipherable noises: "Eat up, boys! Eat and grow and get strong. You're going to need it, where you're going!"

And then there would be a sound like a jackal's yelping and the two-legs would move off and feed the other creatures imprisoned in different parts of the darkness.

Brown bears. Jackals. A group of monkeys, squabbling and chattering hysterically. There were wild dogs, barking incessantly and giving off a terrible stench of anger and fear. There were peacocks with huge rustling tails, that spoke in screeches. And somewhere quite far away, a she-elephant, with something fastened to her legs that made an unnatural clanking sound as she moved her great body from foot to foot in the creaking, shifting, never-ending dark.

One night the dogs began to bite and tear at each other amid an outburst of snarling and shrieking sounds. The cubs were afraid and huddled down in the farthest corner of their prison. But they could hear the wild battles as one dog after another succumbed and was torn to pieces. The next time the sky opened, the two-legged animals found a scene of carnage, with only two dogs left alive.

"There'll be trouble now," one muttered, as he dragged the remains out from a half-opening while others held the survivors off with pointed sticks.

"I said they should have put 'em all in separate cages. They'll say we didn't feed 'em enough."

"Better cut the corpses up and give the meat to the tigers. Dogs is one thing, but if we lose one of them cubs, we'll be dog meat ourselves."

After that there was no shortage of food and the cubs spent most of the time when they weren't eating, sleeping off their huge meals. But their sleep was not peaceful.

The cubs had no desire to fight or kill each other. They didn't know they were brothers, but each knew that the other was all he had. One was the firstborn and the larger. He was the leader. In the jungle, he had been fed first and most, and had led their games and pretend hunts. He was also the more intelligent of the two. He came to understand that it was no use howling and scratching at the ground and rubbing backward and forward with cheek and sides against the cold, close-together barriers, or trying to chew them to pieces. When his brother did these things, he would knock him down with his paw and lie on him to stop him.

The younger one would submit. It was better, he found. His paws, throat, and teeth stopped being sore. He learned to save his energies. But the misery was still there. It only stopped while he ate, and when he curled up with his brother and they licked each other's faces, and slept.