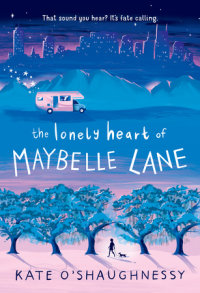

The Lonely Heart of Maybelle Lane

Maybelle Lane is looking for her father, but on the road to Nashville she finds so much more: courage, brains, heart--and true friends.

Eleven-year-old Maybelle Lane collects sounds. She records the Louisiana crickets chirping, Momma strumming her guitar, their broken trailer door squeaking. But the crown jewel of her collection is a sound she didn't collect herself: an old recording of her daddy's warm-sunshine laugh, saved on an old phone's voicemail. It's the only thing she has of his, and the only thing she knows about him.

Until the day she hears that laugh--his laugh--pouring out of the car radio. Going against Momma's wishes, Maybelle starts listening to her radio DJ daddy's new show, drinking in every word like a plant leaning toward the sun. When he announces he'll be the judge of a singing contest in Nashville, she signs up. What better way to meet than to stand before him and sing with all her heart?

But the road to Nashville is bumpy. Her starch-stiff neighbor Mrs. Boggs offers to drive her in her RV. And a bully of a boy from the trailer park hitches a ride, too. These are not the people May would have chosen to help her, but it turns out they're searching for things as well. And the journey will mold them into the best kind of family--the kind you choose for yourself.

An Excerpt fromThe Lonely Heart of Maybelle Lane

Chapter 1

Most people don’t think fate has a sound.

But it does. Everything has a sound if you listen carefully enough.

For example: Loneliness sounds like the drip-drop of a leaky faucet, or the clomp of footsteps in an empty parking lot. Dread is the vrr-vrr-vrr of a car engine that won’t start. Love is the sound of Momma strumming her guitar and singing softly beneath her breath. And happiness? At the time, I didn’t know what the sound of happiness was. I hadn’t found it yet.

As for fate, I imagine no two individual fates sound exactly the same. Yours might be the rip of an envelope or the ringing of a phone in the middle of the night. Mine arrived sounding like the deep, night-sky purr of a voice on the radio. Though, of course, I didn’t know it was my fate at the time.

Fate was the last thing on my mind that afternoon. It was the second week of summer vacation, and Momma and I were in the car on our way to the Shop ’n Save. I had a plastic bag full of coupons sticking to my bare legs, and the plastic beads on my necklace were knicker-knacking in the hot, soupy breeze coming in through my window.

I usually loved trips to the Shop ’n Save. We went twice a month, and Momma let me pick out one special snack just for me, no matter how unhealthy it was. I would spend the whole car ride thinking about what I wanted. Sometimes I chose a king-size bag of Skittles (I always saved the orange ones for Momma), and other times, I got a box of Ritz Crackers and a can of Easy Cheese.

But on that afternoon, the only thing I could think about was the torn top of Momma’s special letter, sticking out of one of the cup holders. I could tell it was the only thing she could think about, too, because she kept running her fingers over its ragged edge, like she wanted to reassure herself it was real.

Maybe she could tell my thoughts were in a stormy swirl, because she reached out and squeezed my hand. “May, I won’t do it. Not if you don’t want me to. Three weeks is a long time for me to be gone—”

“No,” I said. “You have to do it. I’ll be fine. I swear.”

The letter was from the director of entertainment for Royale Cruises, and it was about a job as a musician on their fanciest ship, Heart of the Sea. Momma had auditioned for it on a whim, after someone who heard her playing at the Pit Stop Bar & Bar-B-Que had handed her a business card.

Getting this job was her dream. It could be her big break, she told me, plus they were paying almost as much for three weeks’ work as Momma usually made in three months. She had no formal training, so she figured she was the unlikeliest person on the planet to get the position.

But she was wrong. Because here was the letter offering her a contract. She’d be going on a bunch of short cruises, shuttling back and forth between Miami and the Bahamas. The letter said she had to be in Miami for crew training in a few weeks.

Three whole weeks. I’d never been without her for much more than a night. Two, at most.

I tried to ignore the tightness in my chest, the painful and heavy thumping of my heart. I couldn’t fall apart, not when she was so happy. So I forced myself to smile. “I’m excited for you, Momma. I’ll be fine.”

“Maybe I could ask your gram to come stay?”

Now that made my smile into something real. I hadn’t seen Gram in a long time. Too long. “Really? You think she would?”

“I hope so.” She smiled back at me. “Thank you for being so understanding. Think what we can do with all that money. And, who knows, maybe this will open more doors. Maybe I can quit answering phones at the auto shop. Maybe they’ll want me to come back and play on some other cruises, too.”

The hope in her voice sounded bright and full, like birdsong.

“Maybe,” I agreed, but all I could think was how that meant even more weeks and months without Momma might loom in my future. I hoped she was only getting caught up in the moment. I stared out the window and focused on my breathing, a long inhale and a long exhale.

Momma drummed her fingers against the steering wheel and hummed a happy tune to herself. After a minute of this, she said, “Hey, pretty, will you put some music on? If you don’t, I’m going to burst out singing myself.”

I must not have responded fast enough, because she tilted her head back and sang out, “She came to me on a cold, dark night. . . .”

“Not that song,” I said quickly. “Please.”

That was the first line to the bedtime song she sang to me every night when I was little. She wrote it for me when I was born.

“Oh, won’t you sing it with me, just once? I haven’t heard that pretty voice of yours in so long. Too long.”

I shook my head. The thought of singing in front of someone else ever again—even Momma—made me feel sick to my stomach. “No. Not right now.”

“Okay,” she said, drawing the word out with a sigh. “Fine. If you won’t sing, then be a love and flip on the radio.”

I turned to stare at her. “You want me to turn on the radio? The radio?”

She shrugged as she slowed down at a light and turned on the blinker. “I was cleaning out the car this morning, and I forgot to put the Bible back in.”

Momma rarely forgot her Bible, which was her name for the binder of CDs she kept stashed in the back seat. Our car was old, which meant we had no way of connecting Momma’s phone to its speakers. So we’d spent weekends together scouring thrift shops, looking for her favorites. The Bible had been built up over years. She loved all sorts of music—country, folk, rock, hip-hop, classical, and even that metal stuff, which reminded me of chain saws and the unpleasant screech of chalk on a blackboard. But out of all the music she listened to, she loved the blues the most. She liked the twangy blues of Guitar Slim and Snooks Eaglin and also the rich, soulful crooning of Little Walter, Johnny Adams, and Blind Willie Johnson. Memphis Minnie, B. B. King, Bessie Smith . . . the list went on and on.

But never the radio. For whatever reason, she’d always had a “thing” against the radio, ever since I was little.

“Well, all right.” I reached forward to turn it on. “If you say so.”

Static came out first. On the next station, some angry preacher was hollering about the Lord this and the devil that and something about hellfire, so I pressed the button again. Next was a pop song with a thumping beat. I looked at Momma, but she made a face, so I went to the next station.

And that’s when I heard it. The sound of my fate coming up to meet me.

I could hardly blink or breathe or think. It wasn’t music. It was a voice. Not even singing . . . just talking.

Even though the car’s speakers were old and tinny, the sound of the man’s voice that filled the car was like . . . well, it was like magic. It was the purr of a house cat and the roar of a lion. It was the thrum of the lowest piano key, like velvet and gravel and the deepest, darkest part of the night sky, all at once.

Then that voice laughed. It made me feel like laughing myself, like the whole car had been lit up with rays of sunshine.

And that’s when I realized how familiar it sounded.

I knew that laugh. I knew that laugh deep in my bones.

Momma must have realized it, too, because she made a strange, strangled noise in the back of her throat and flicked off the radio.

But it was too late.

“Momma,” I breathed. I turned to look at her, but she wouldn’t meet my eyes. “That was my daddy’s voice, wasn’t it?”